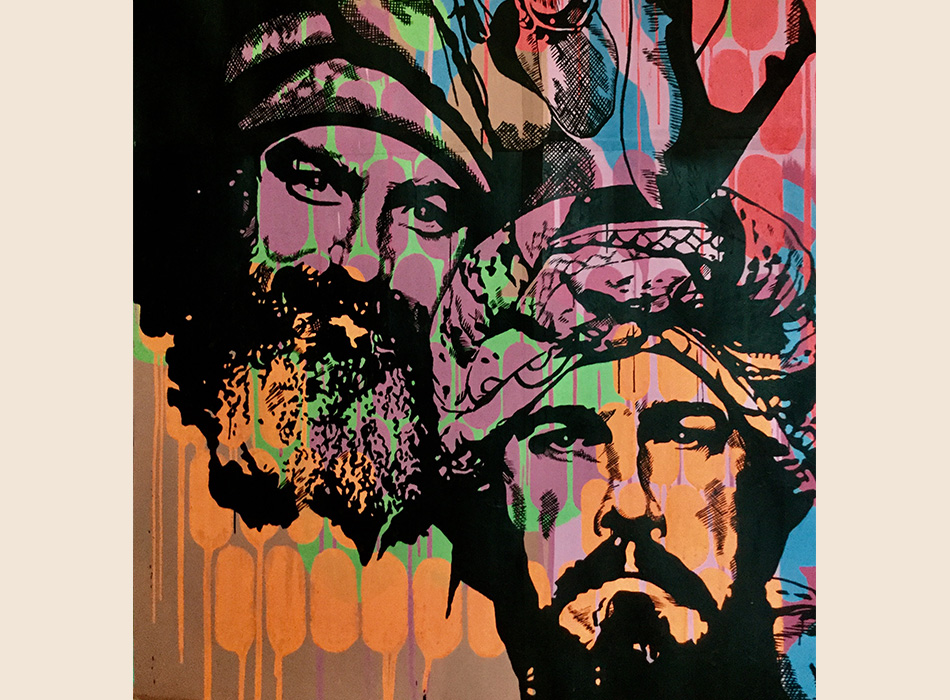

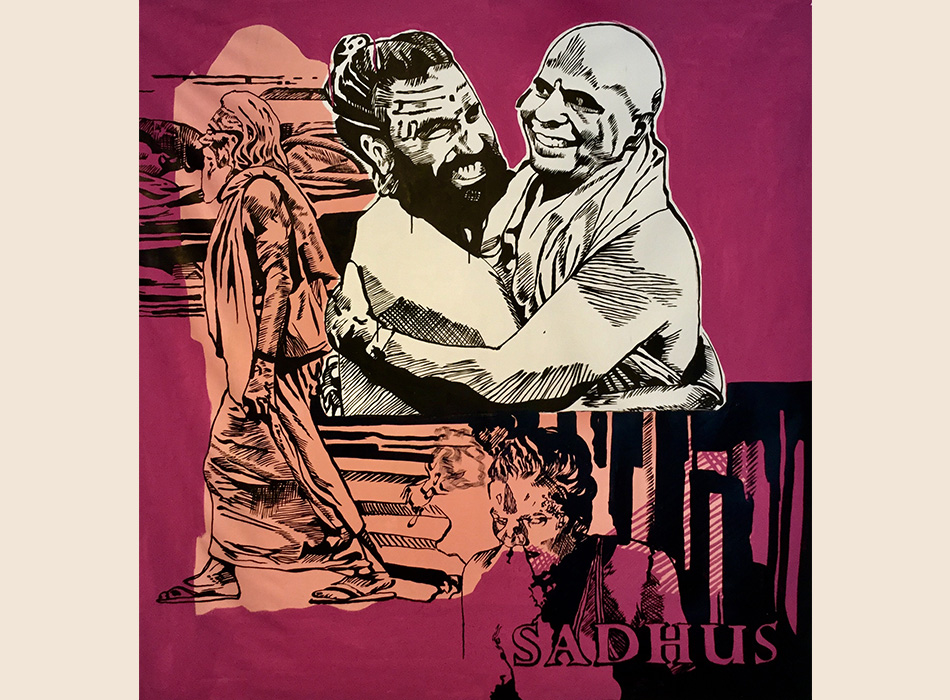

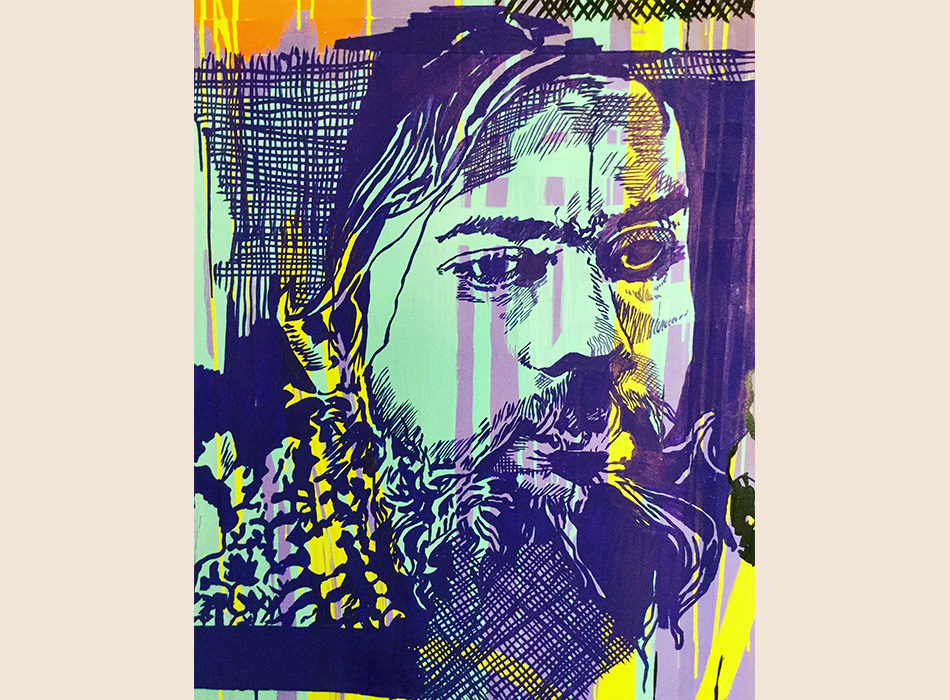

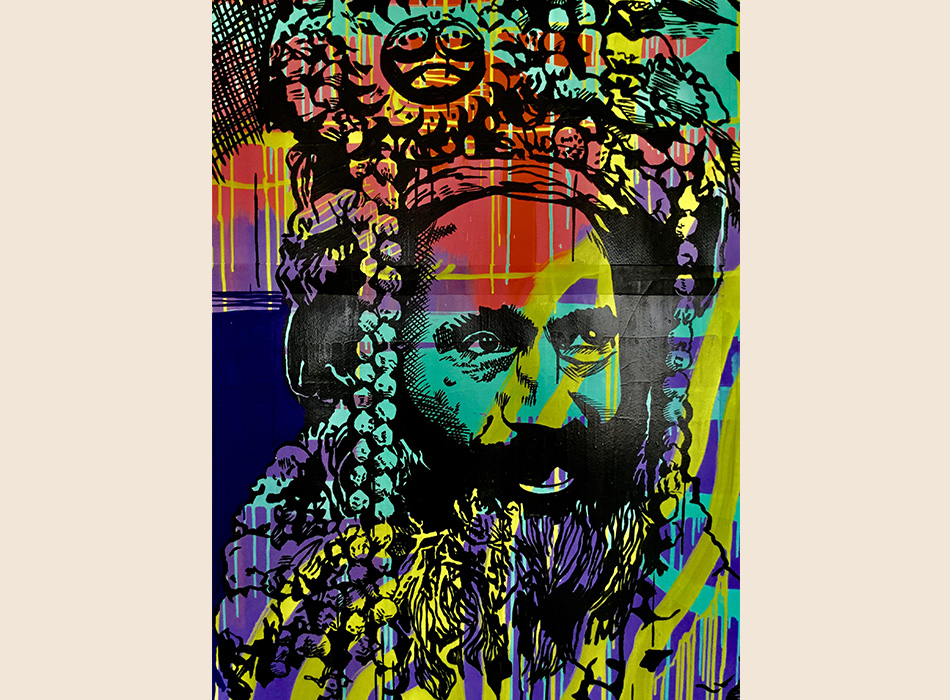

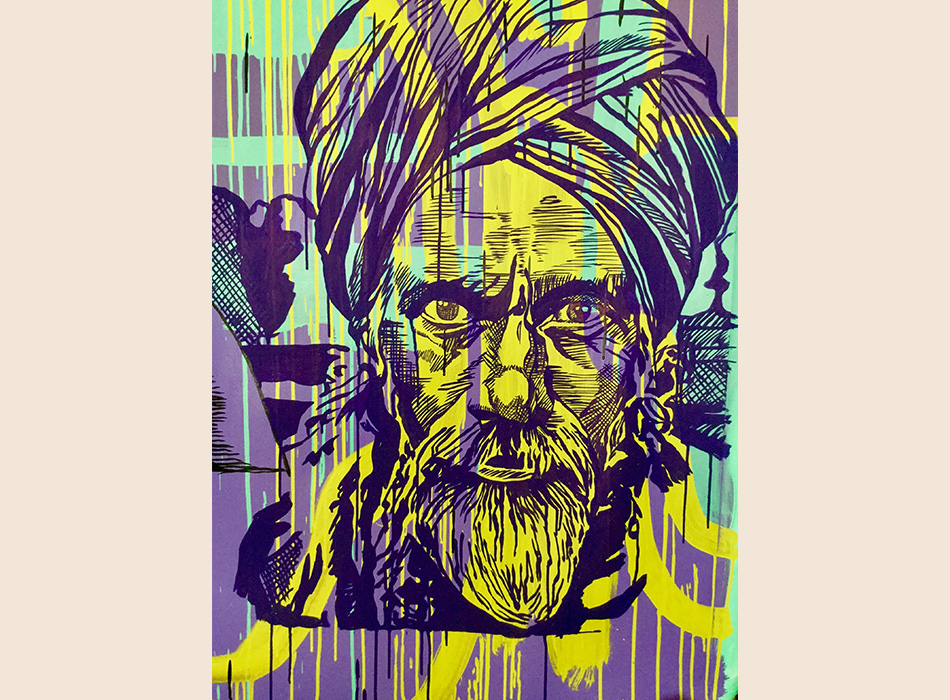

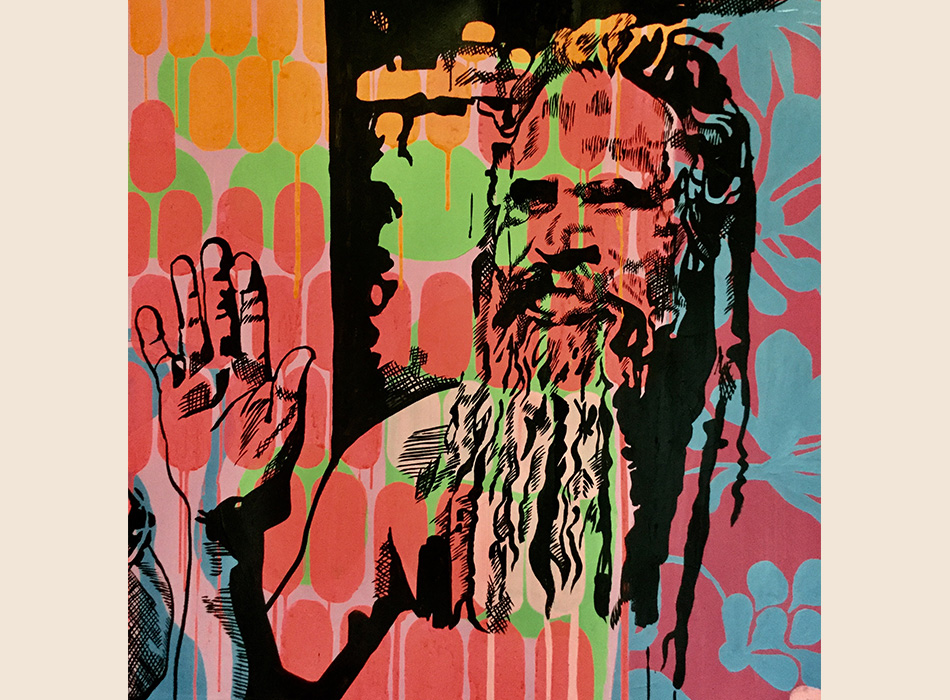

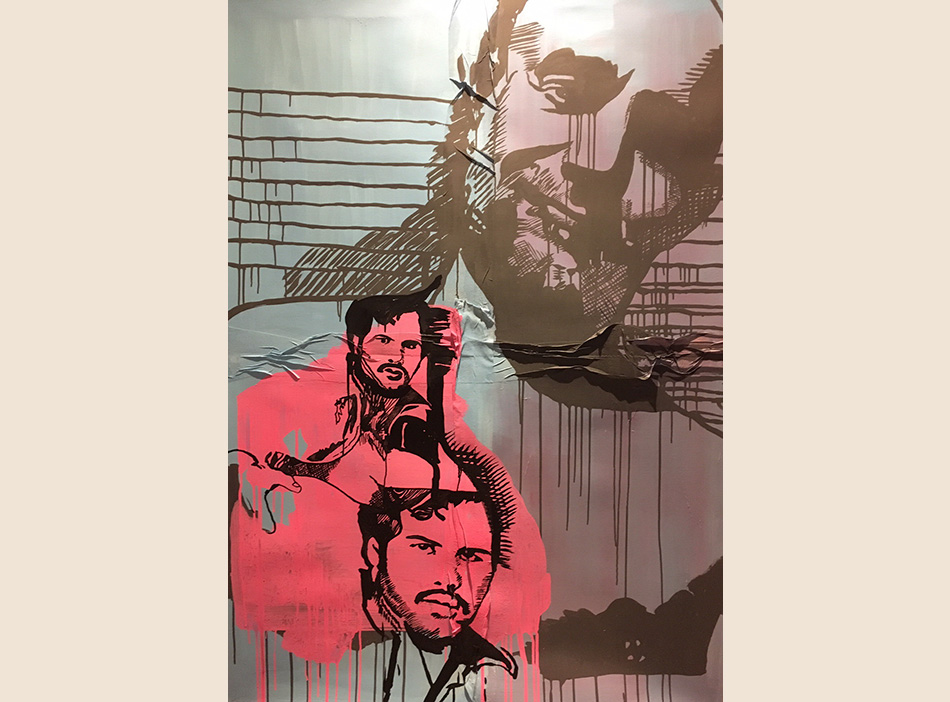

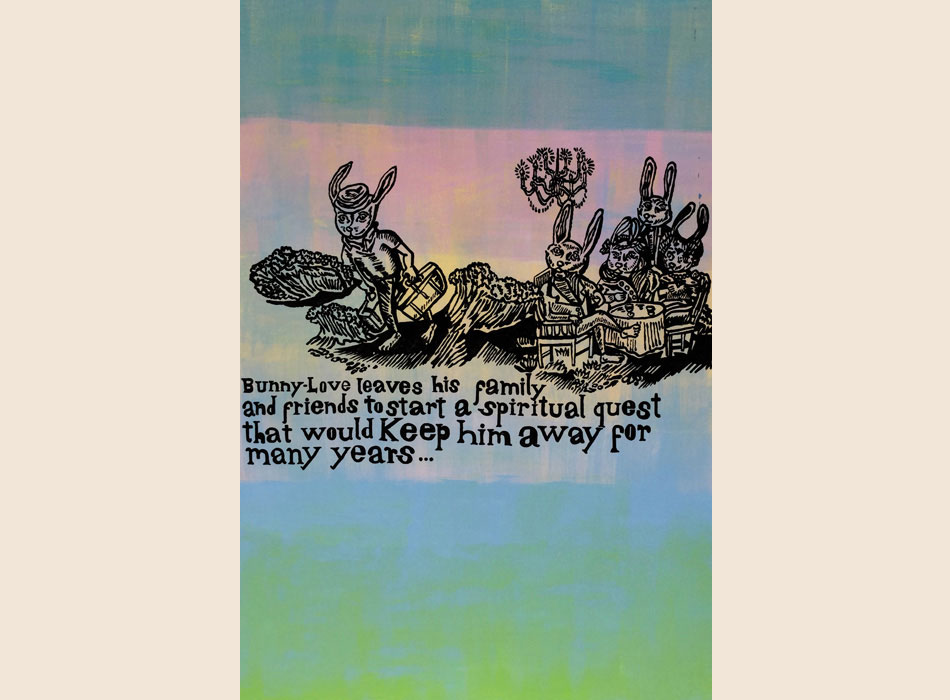

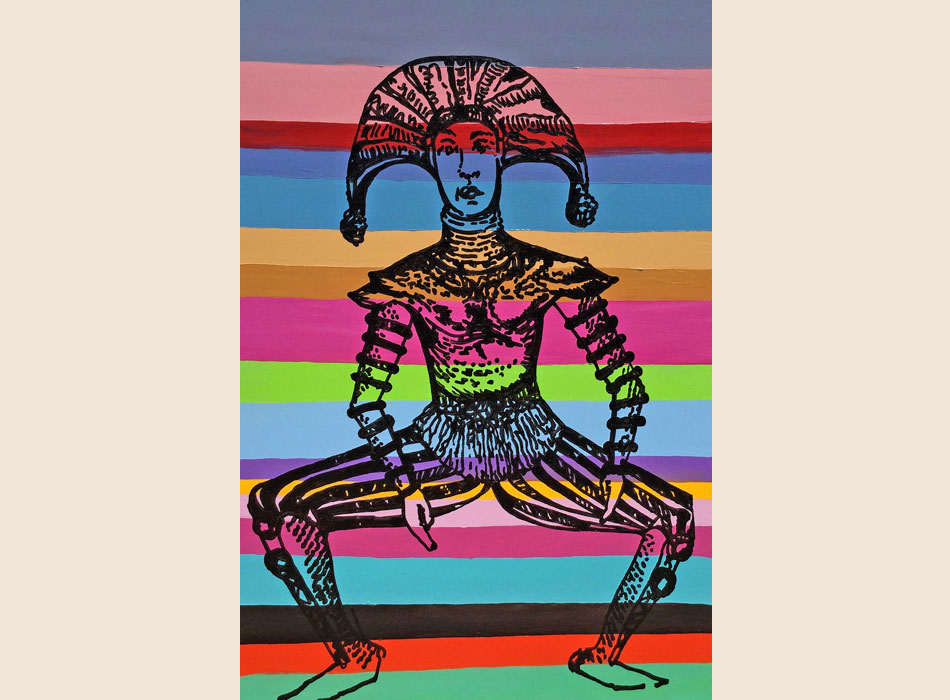

The Sadhus Series

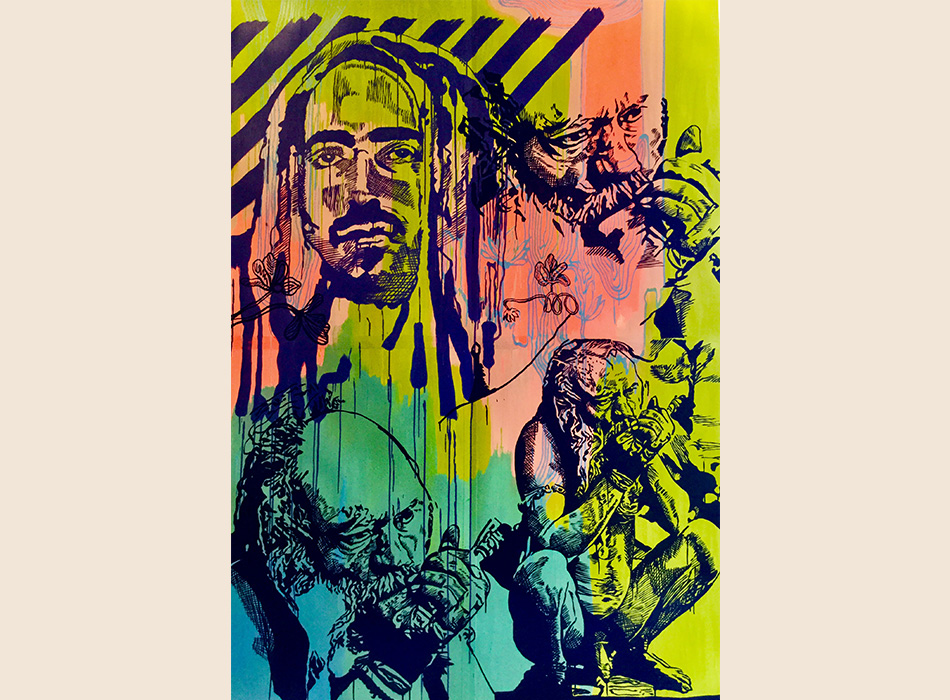

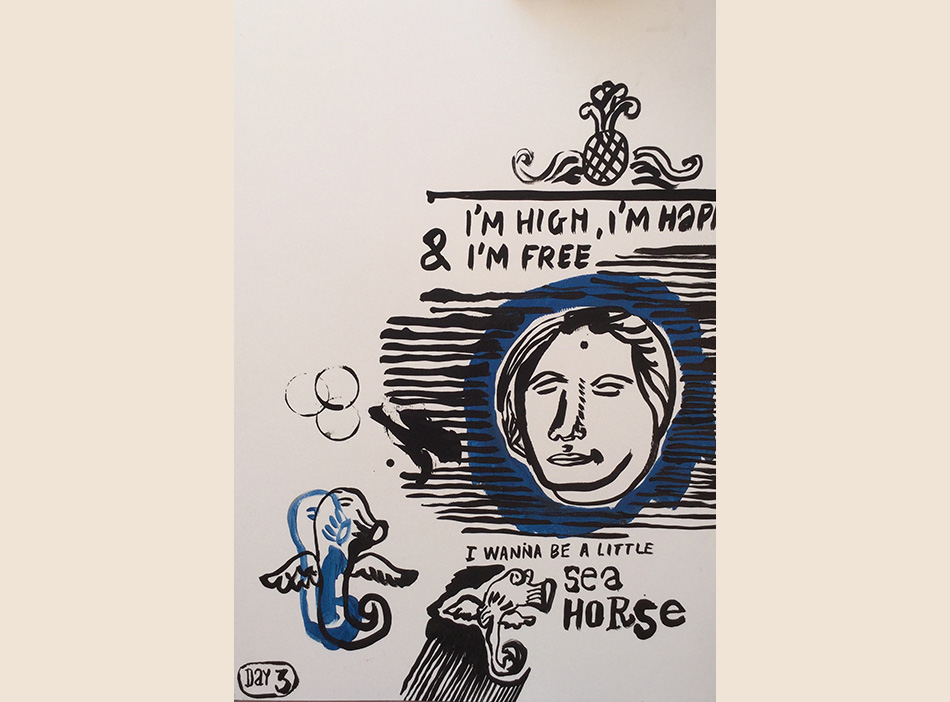

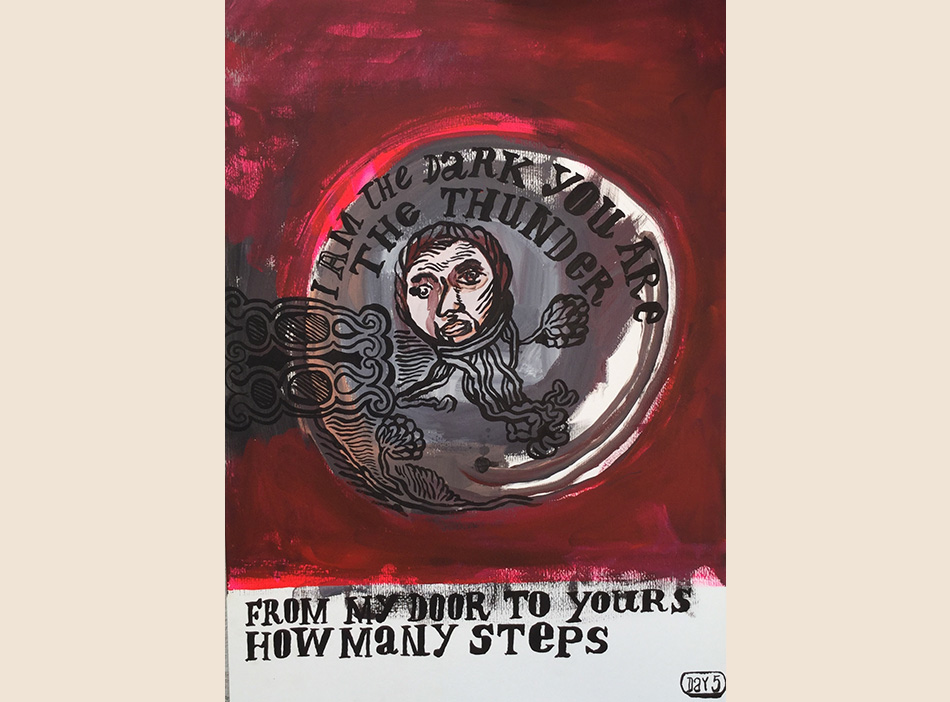

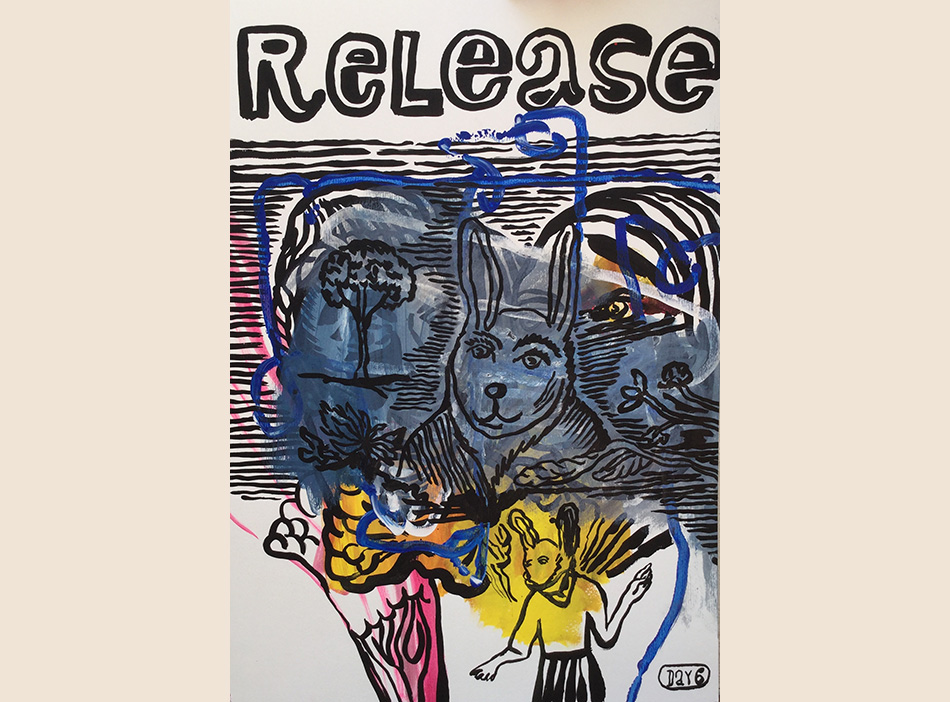

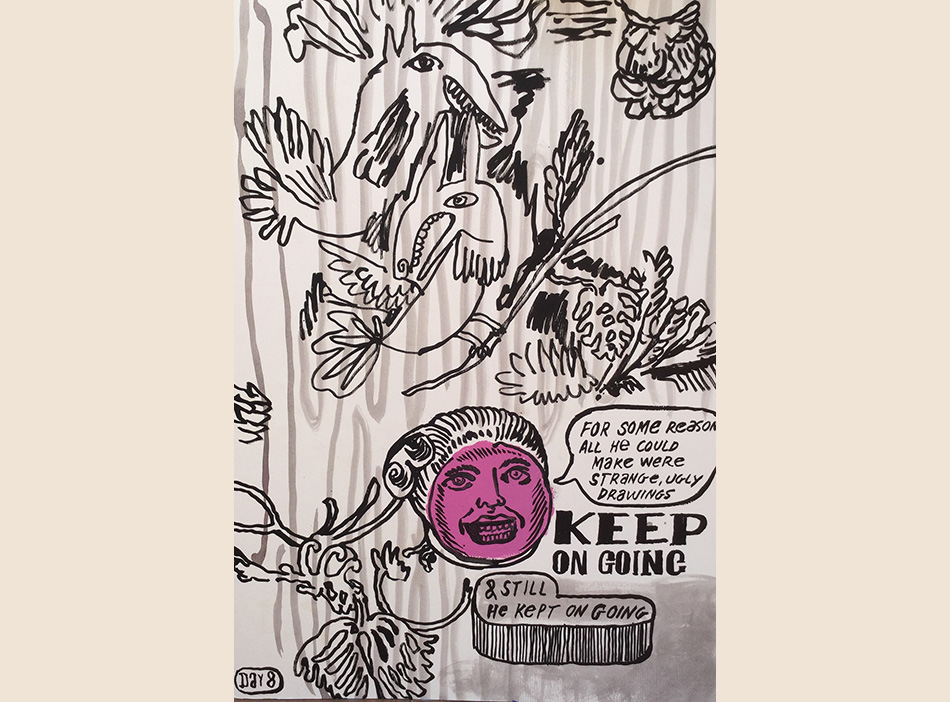

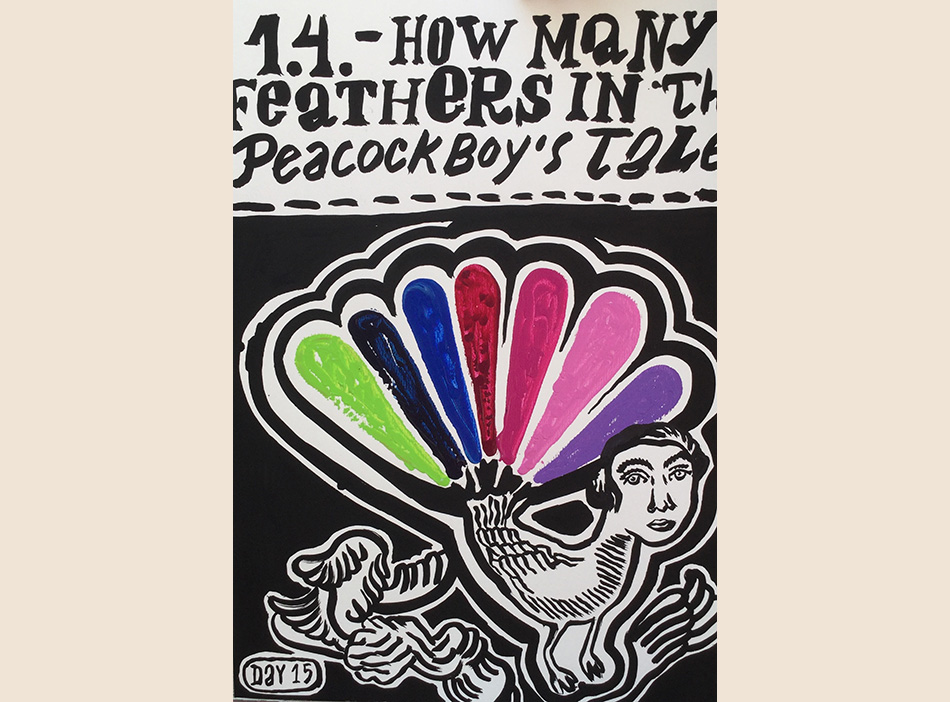

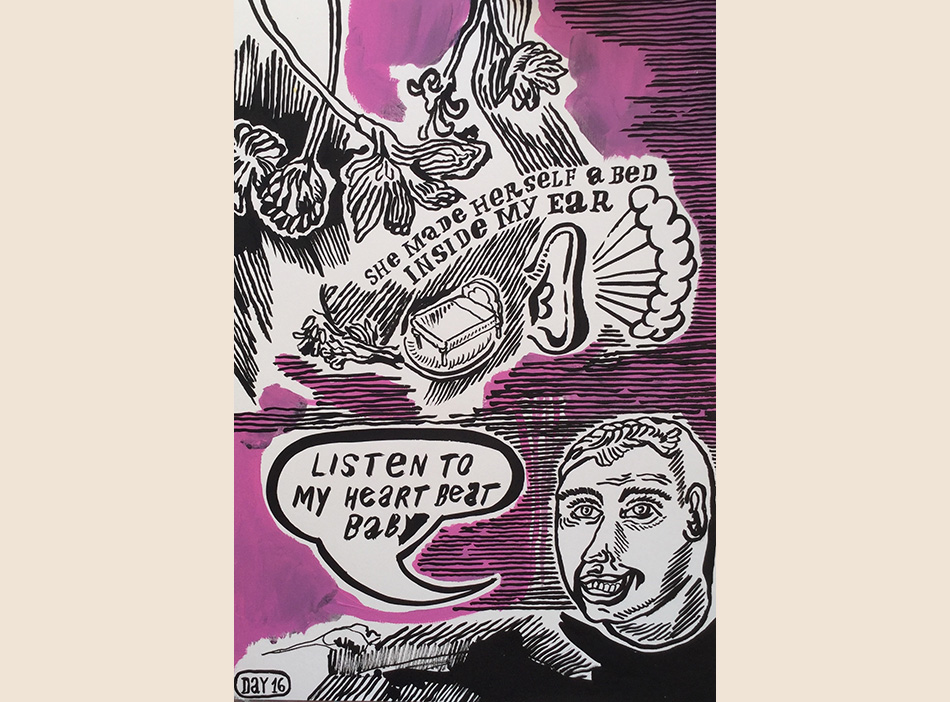

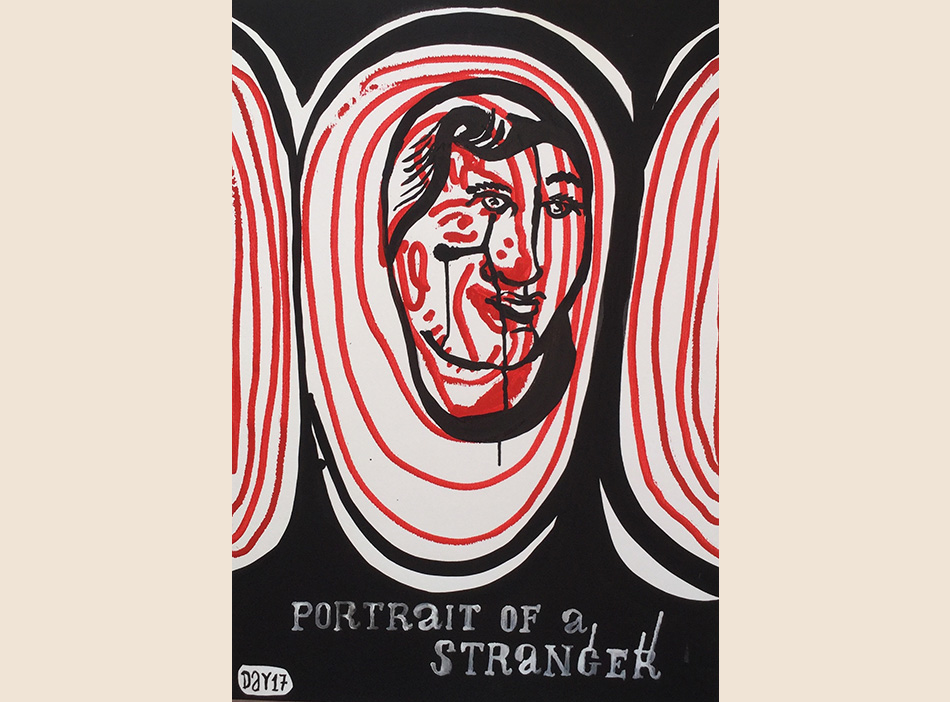

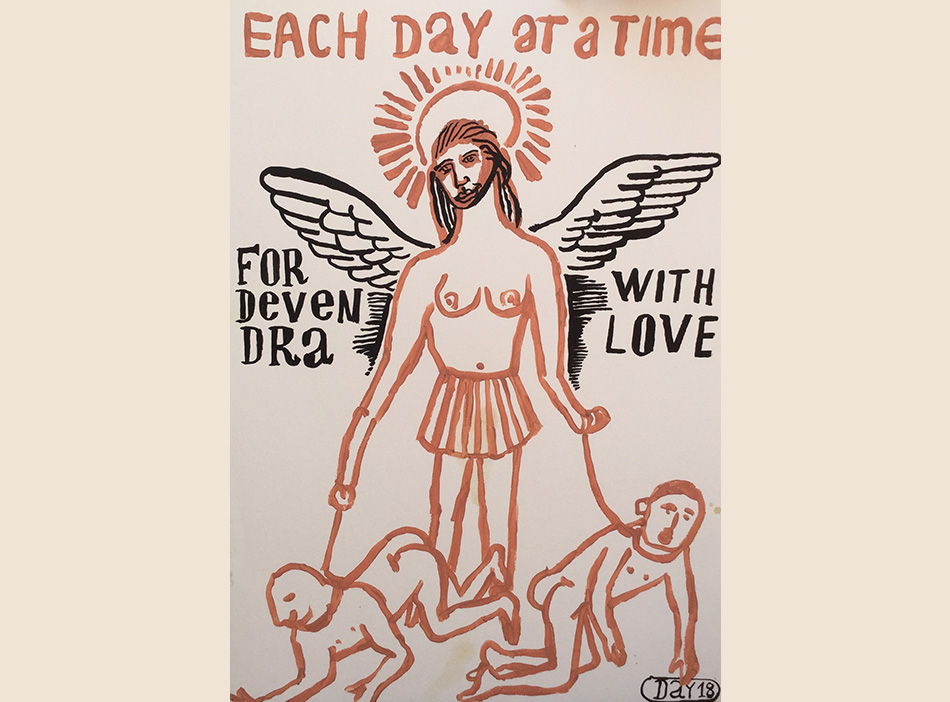

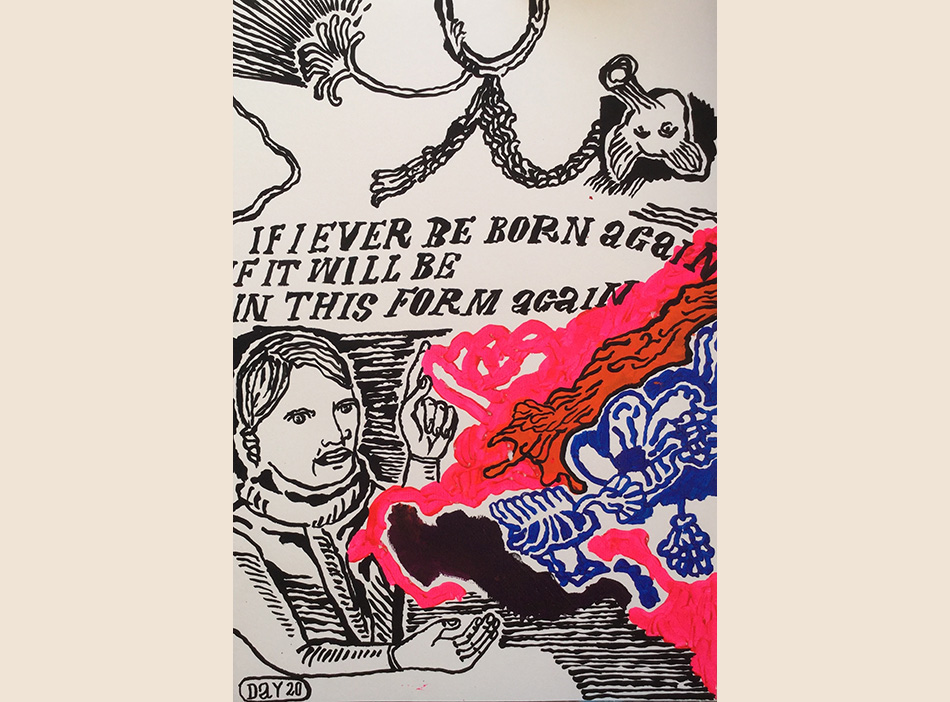

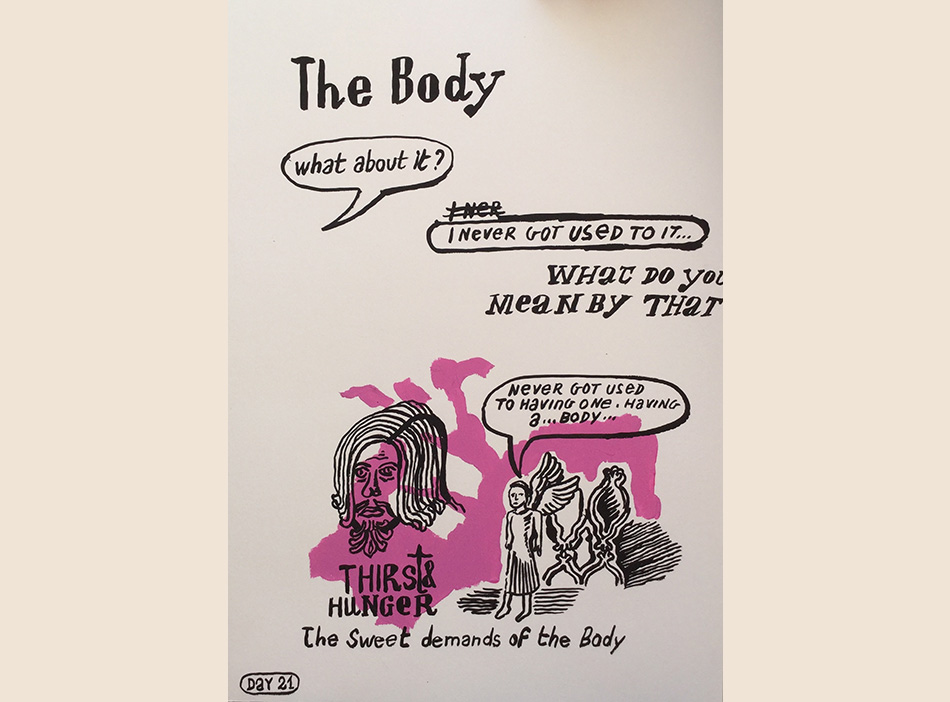

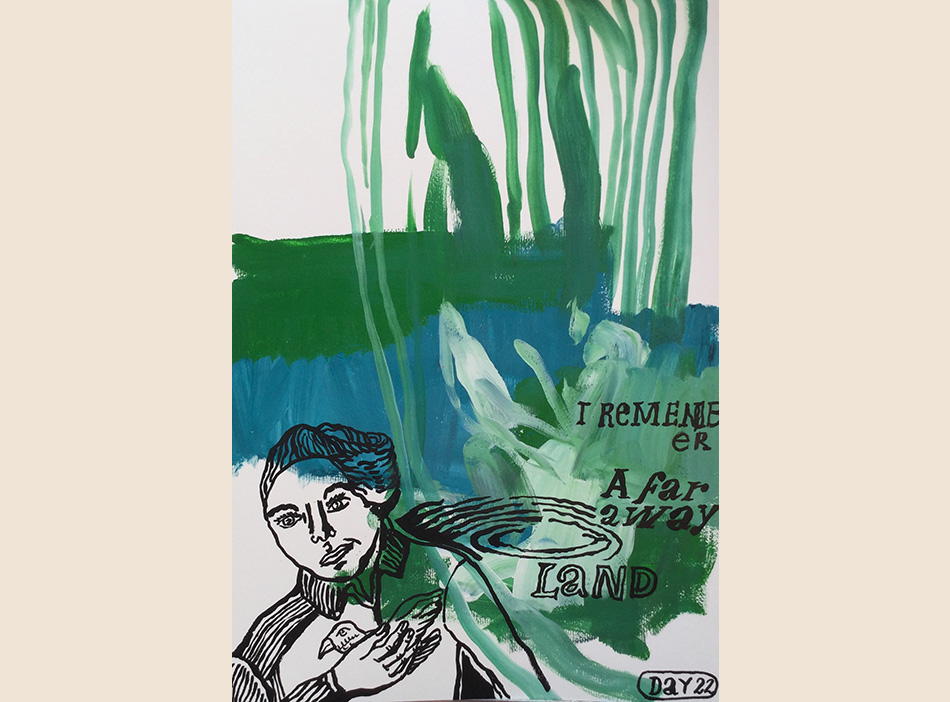

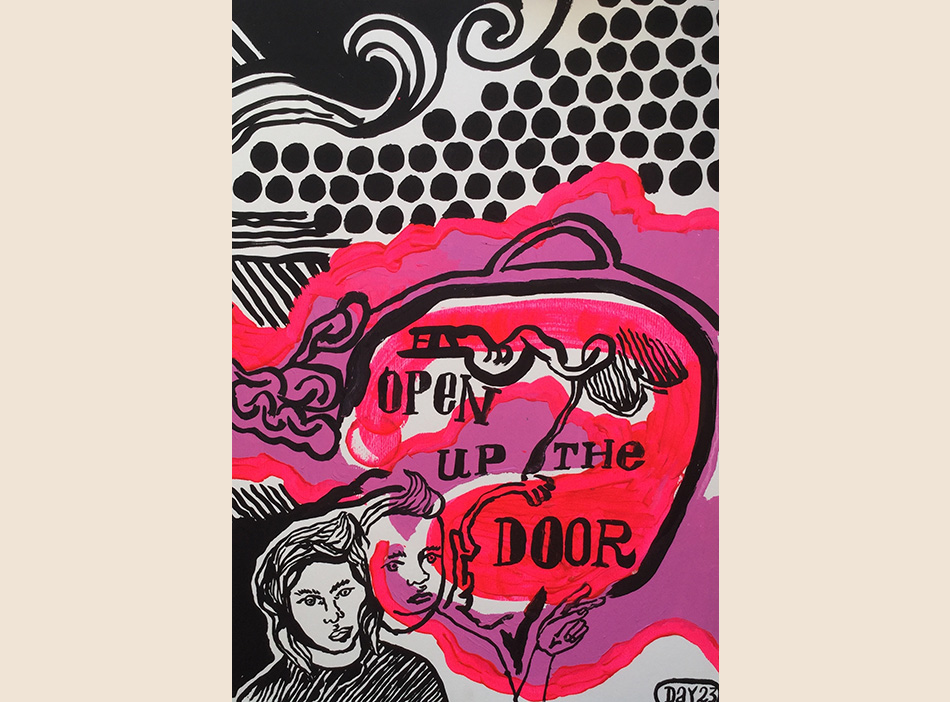

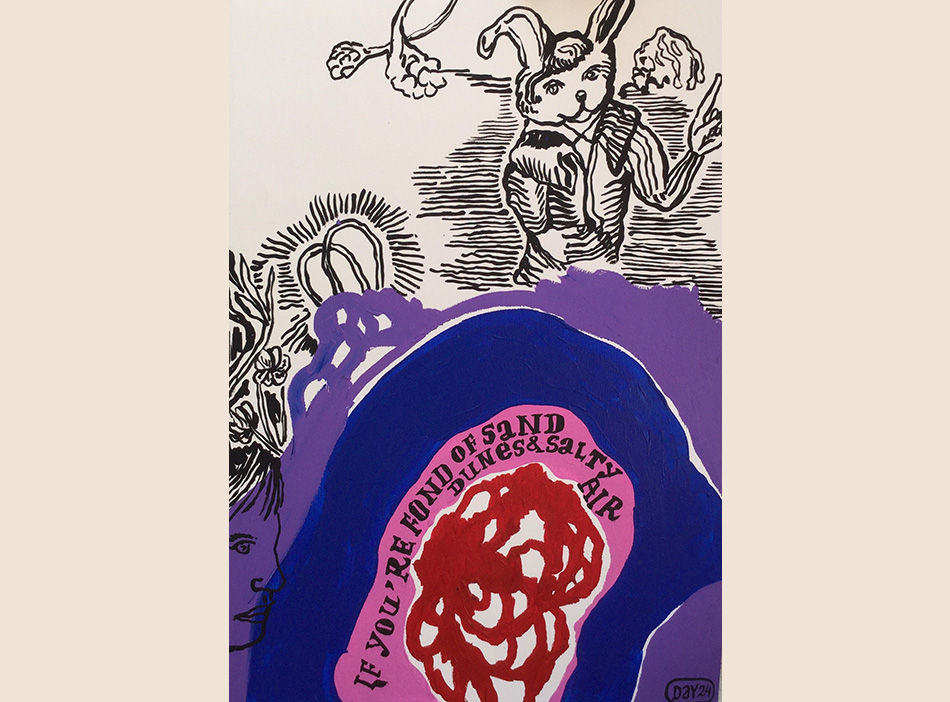

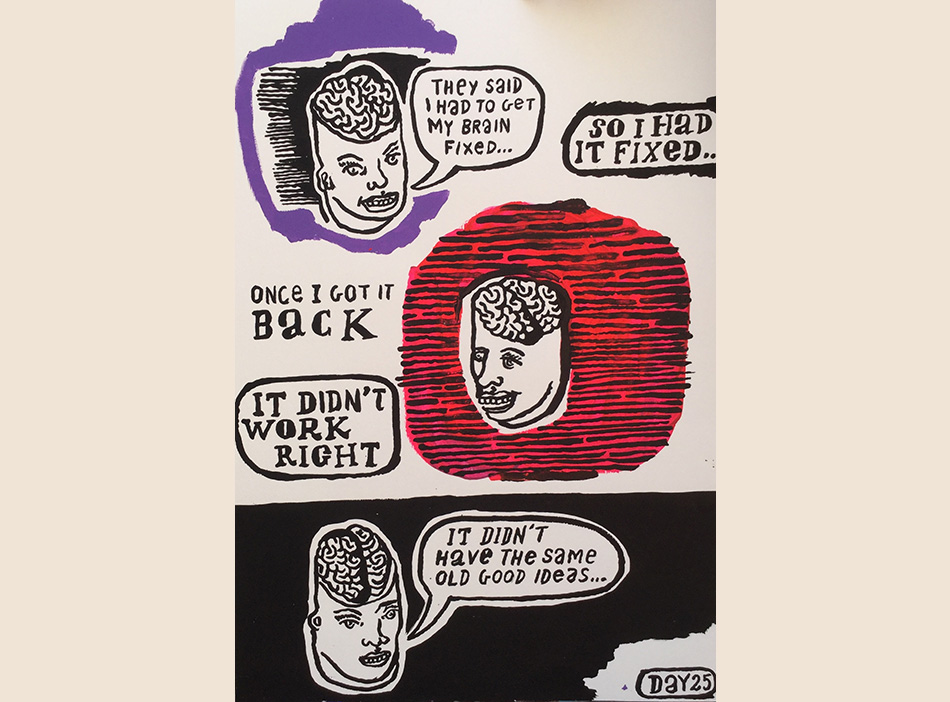

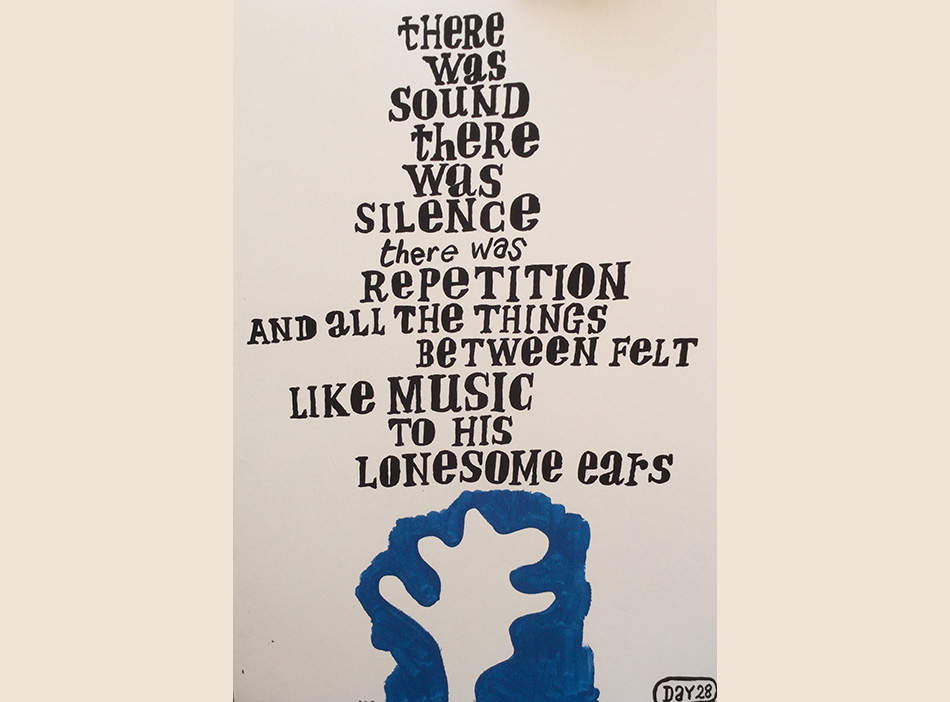

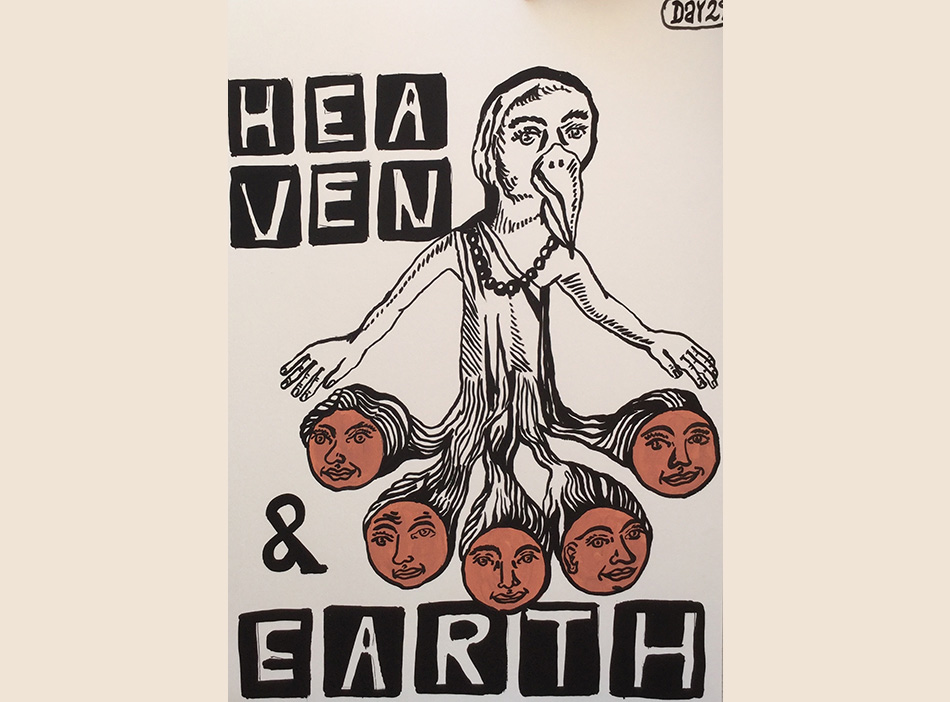

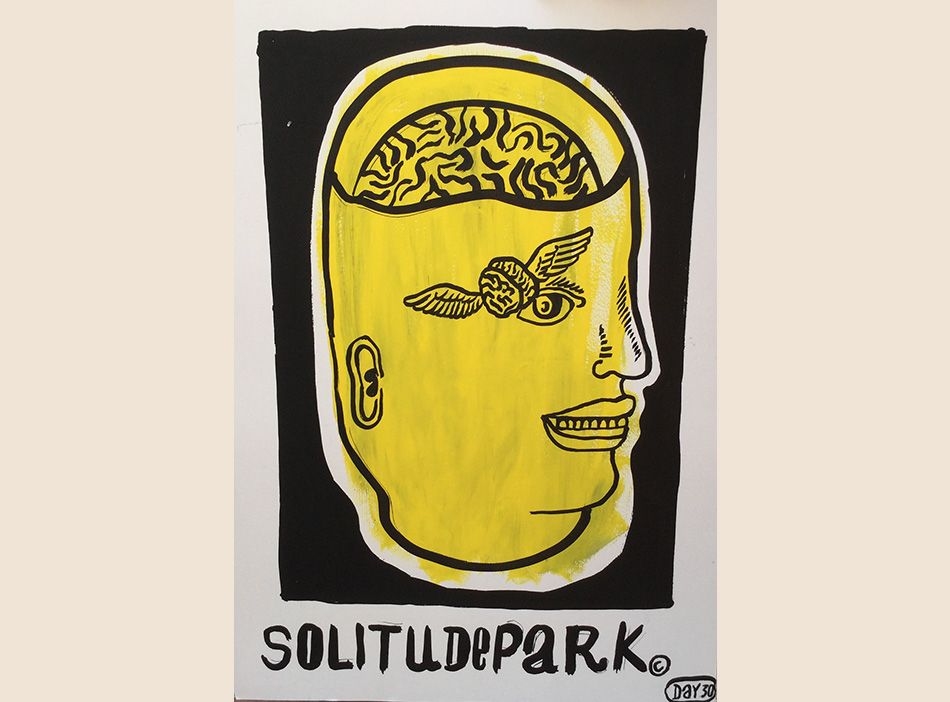

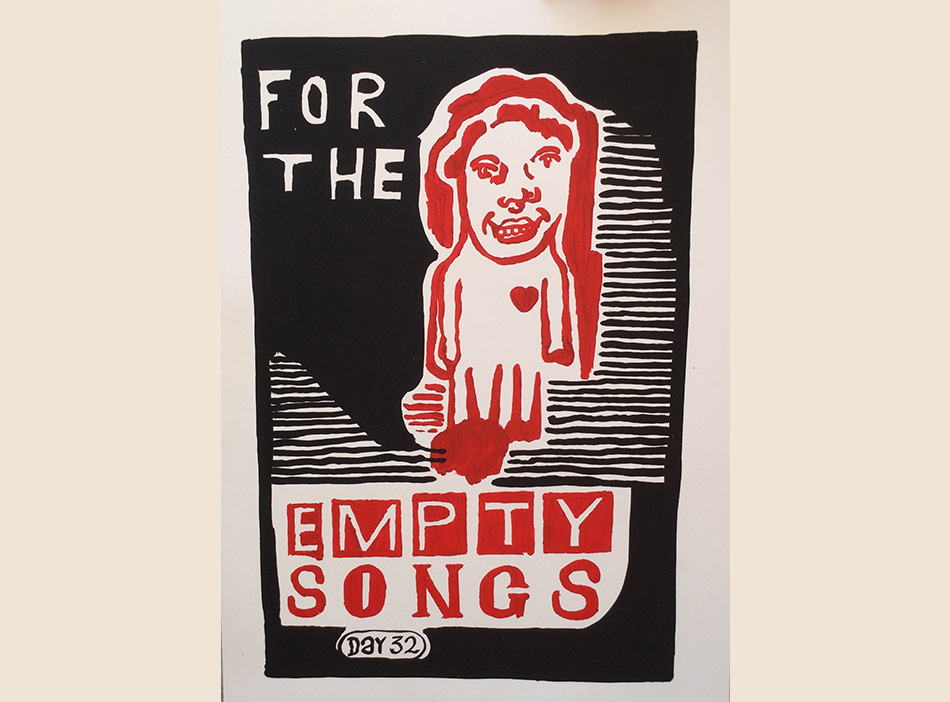

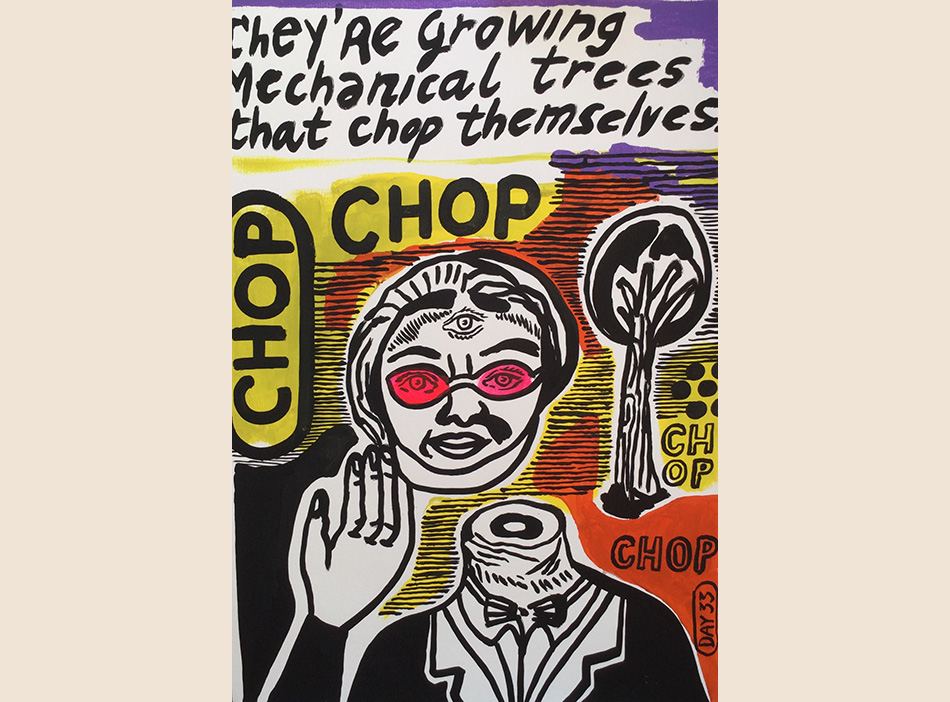

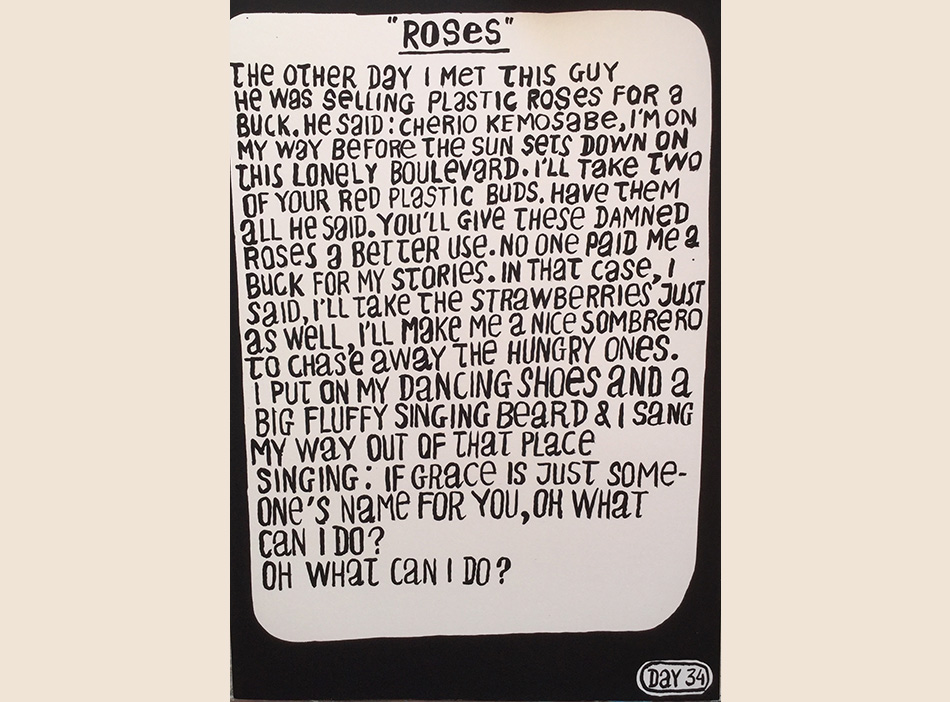

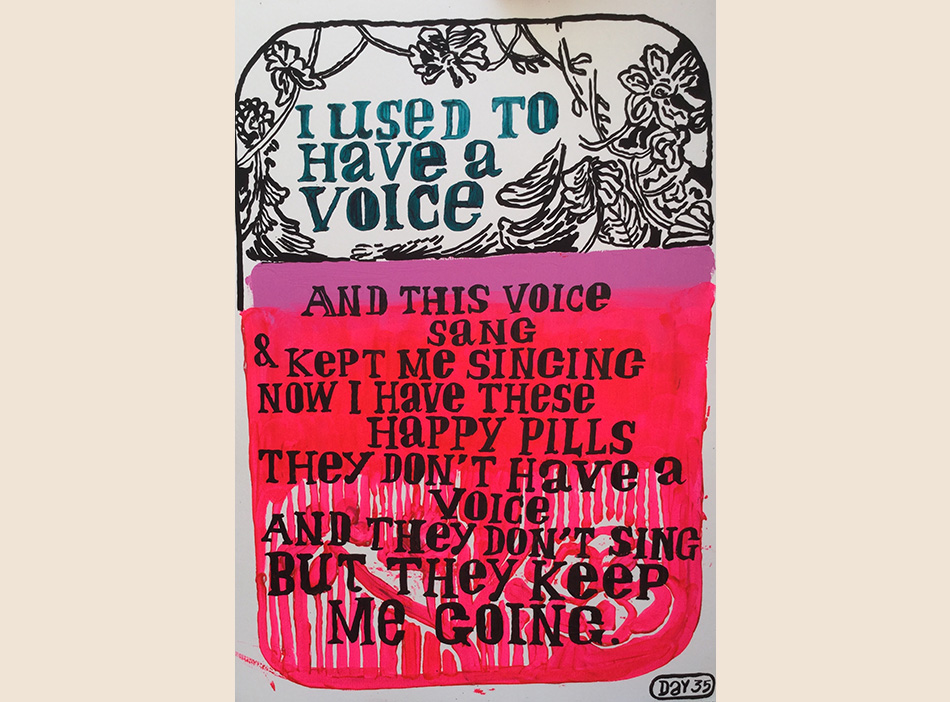

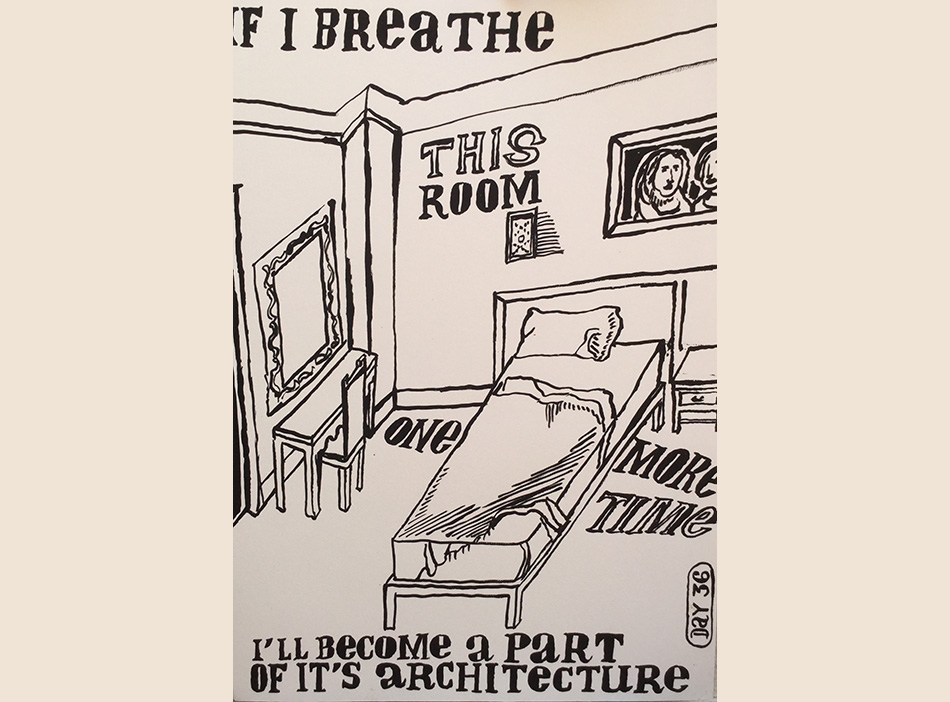

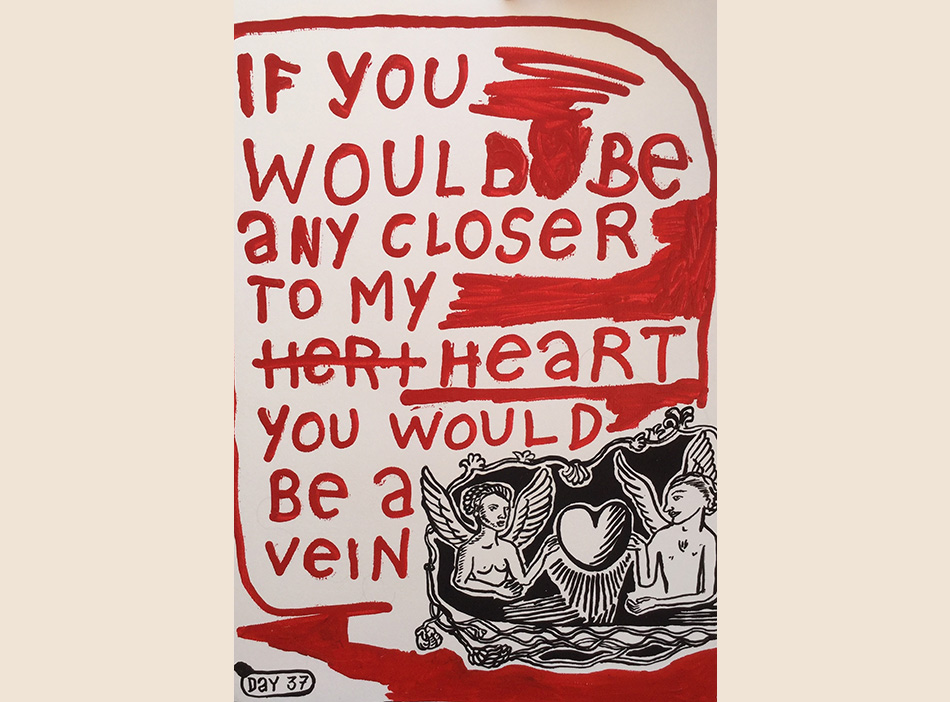

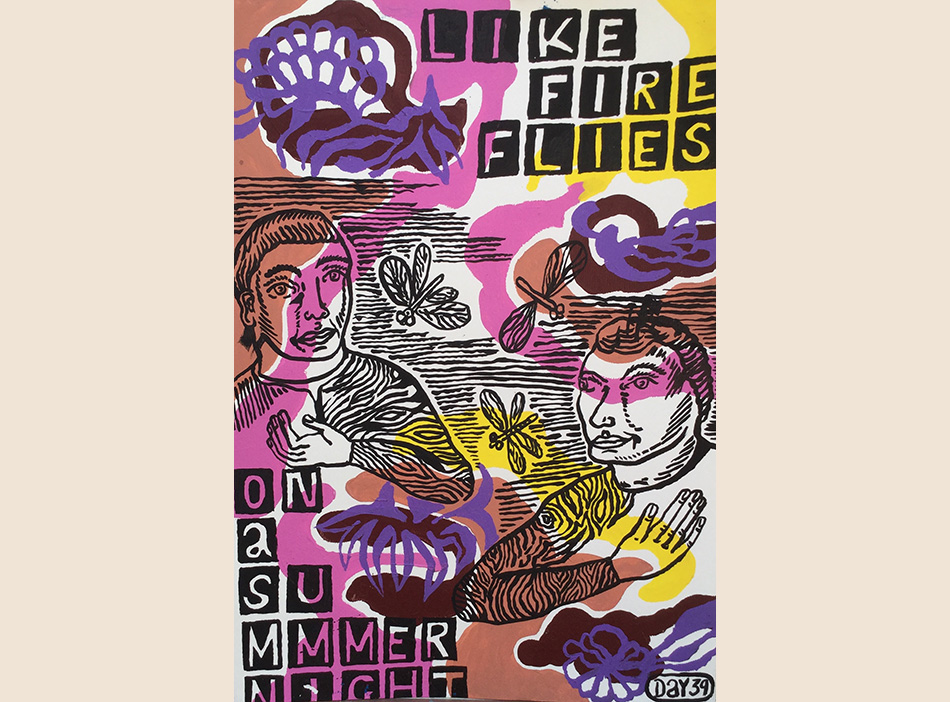

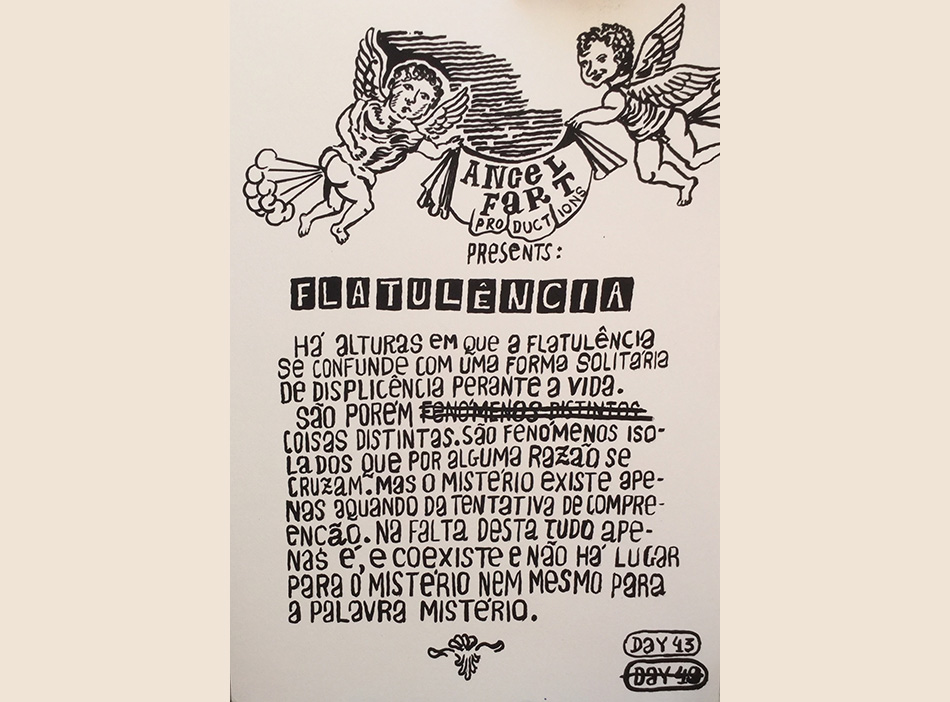

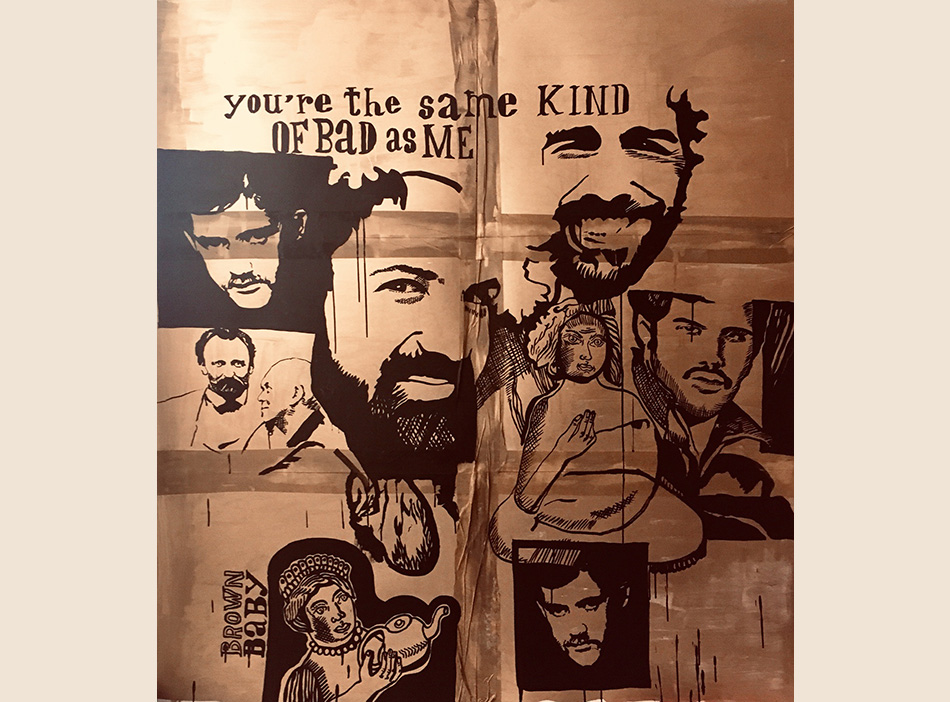

44DAYS When Time is Not Linear and 2 are missing

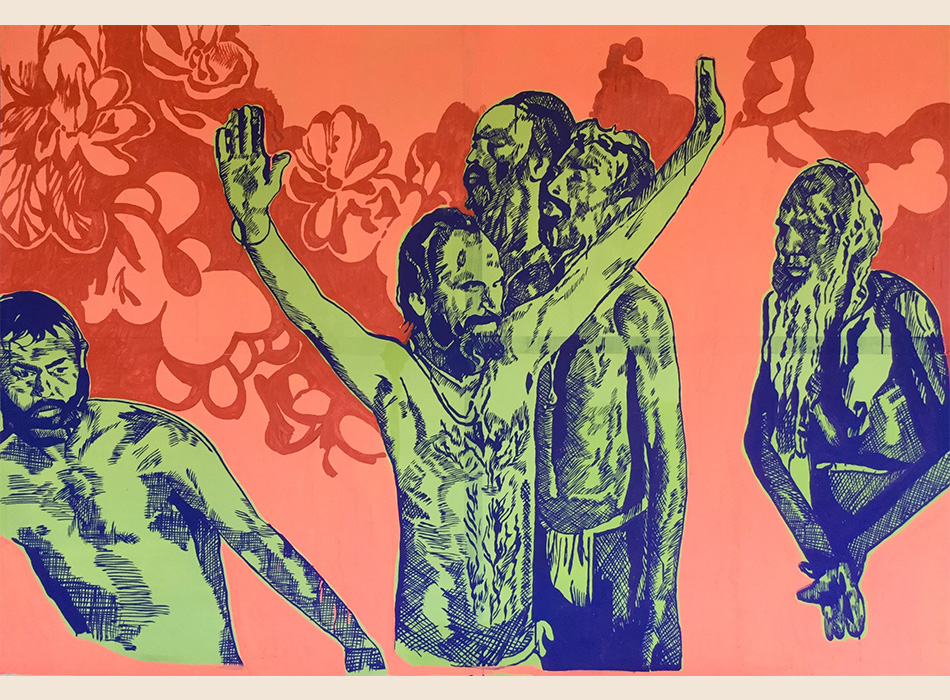

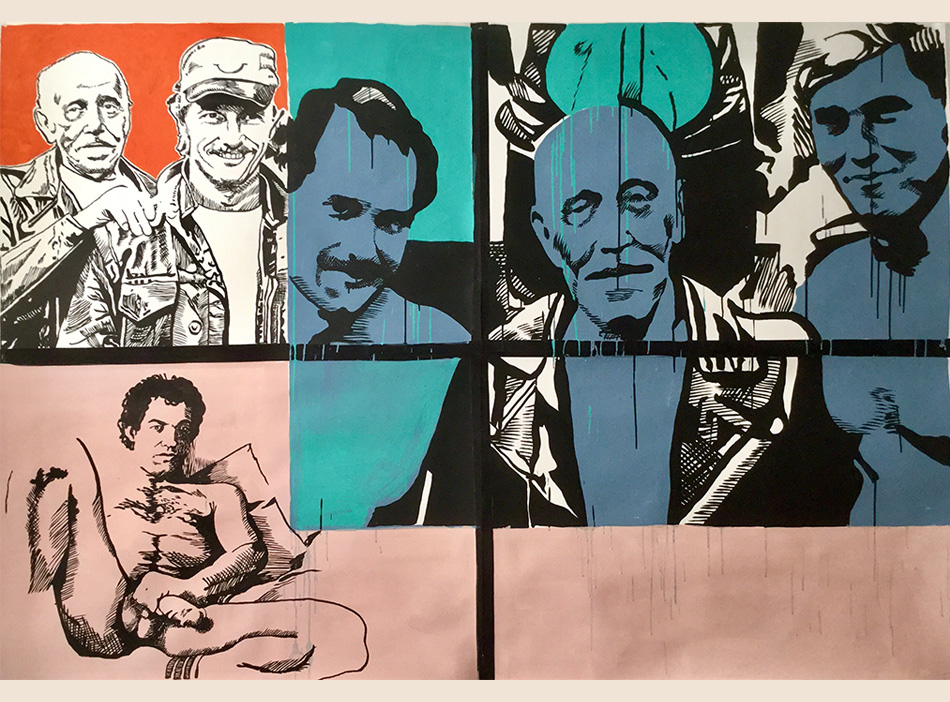

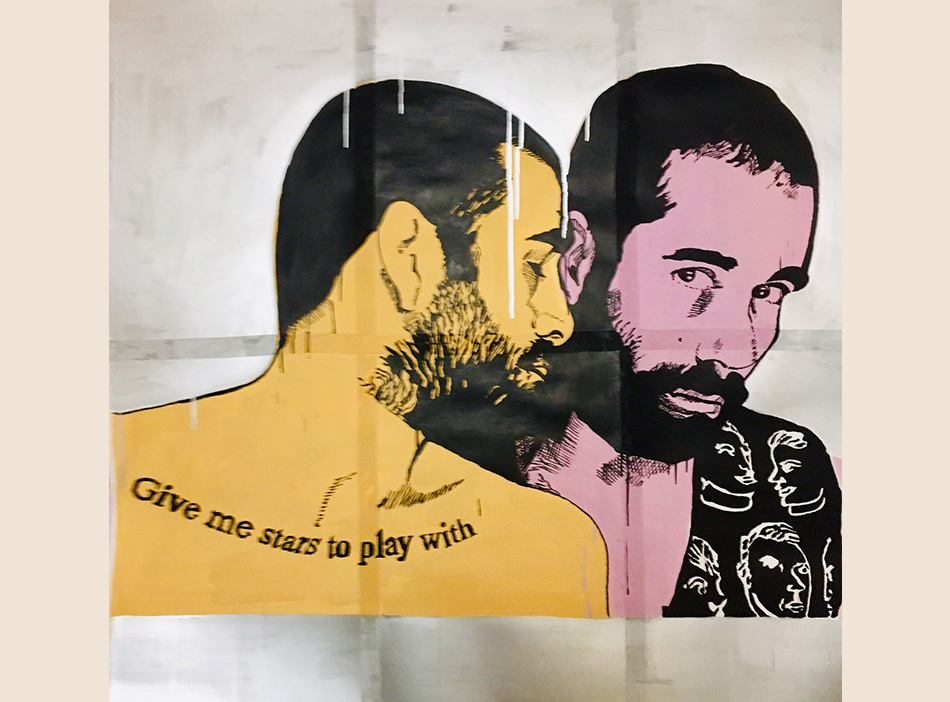

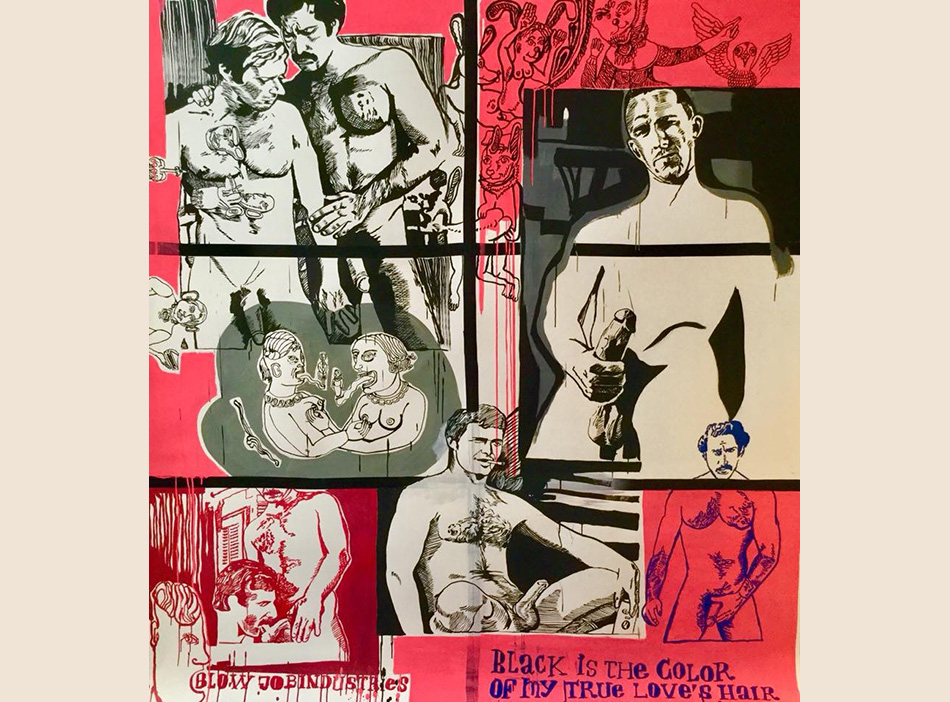

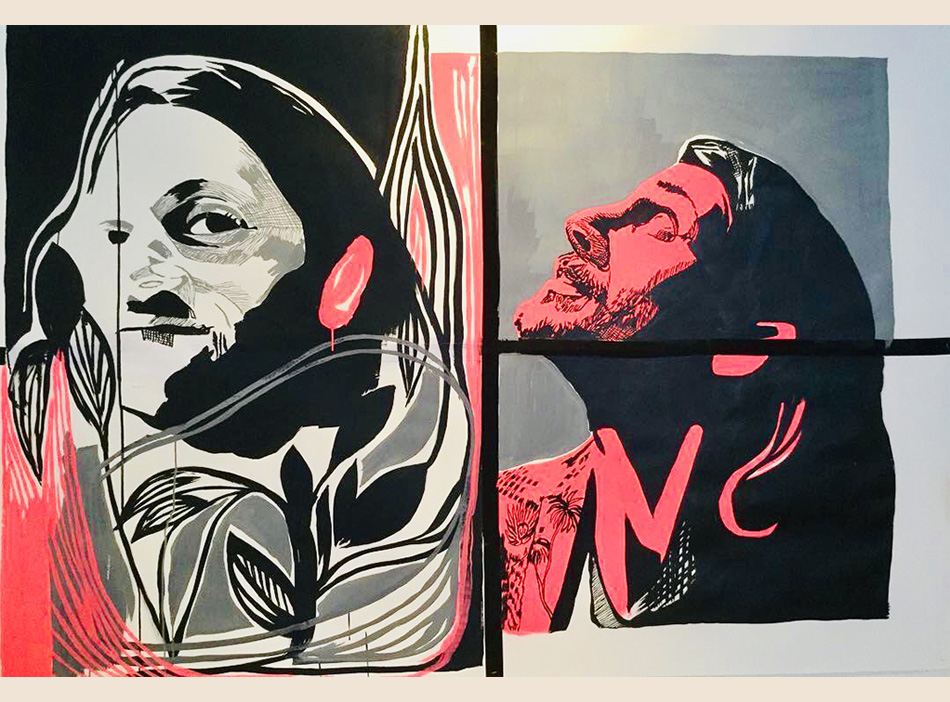

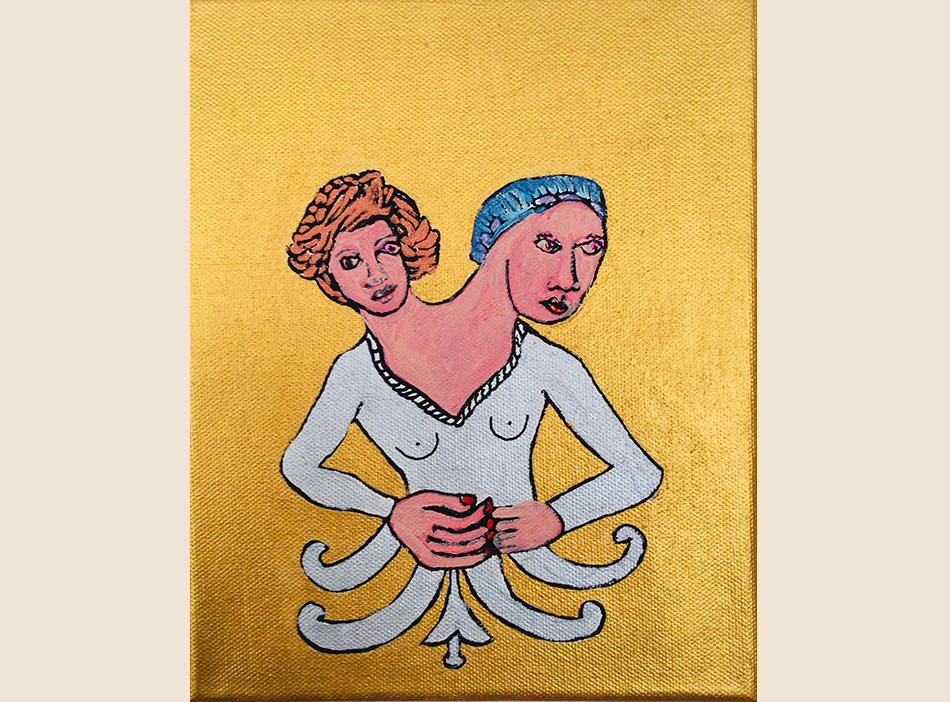

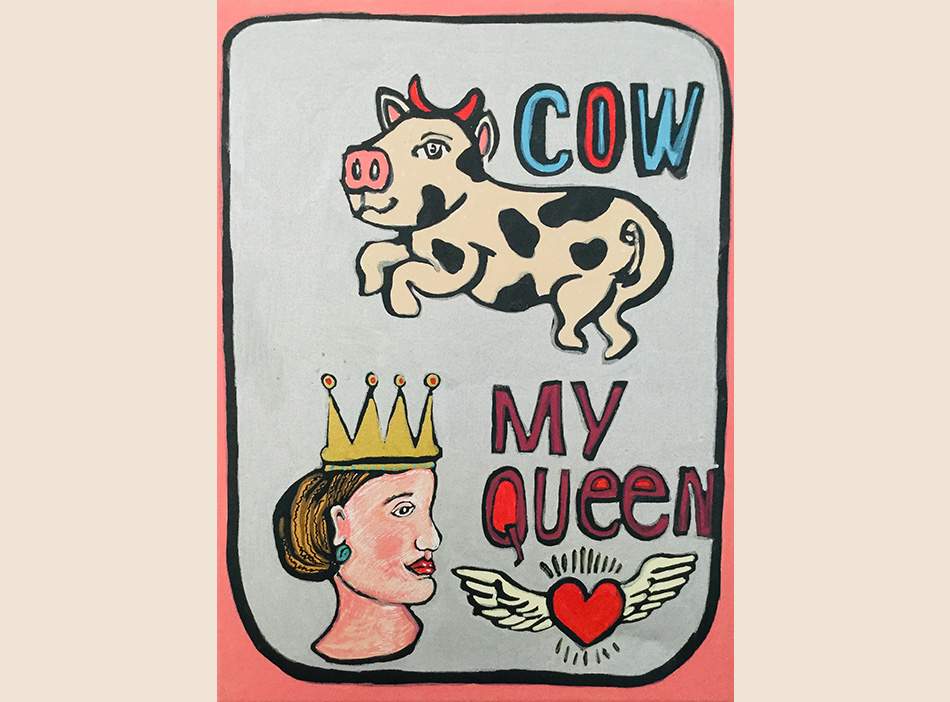

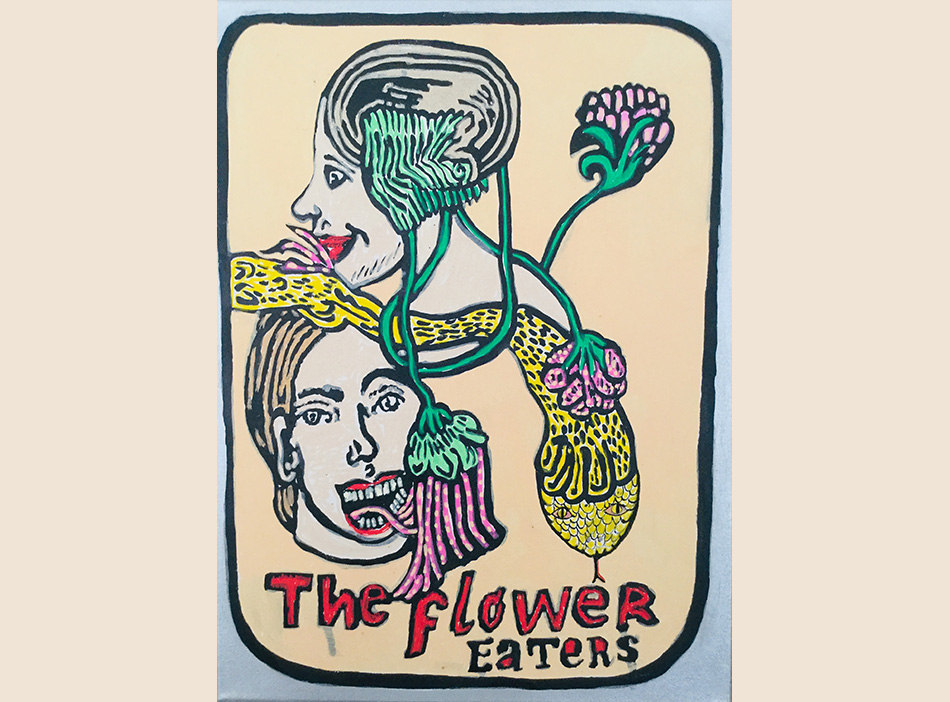

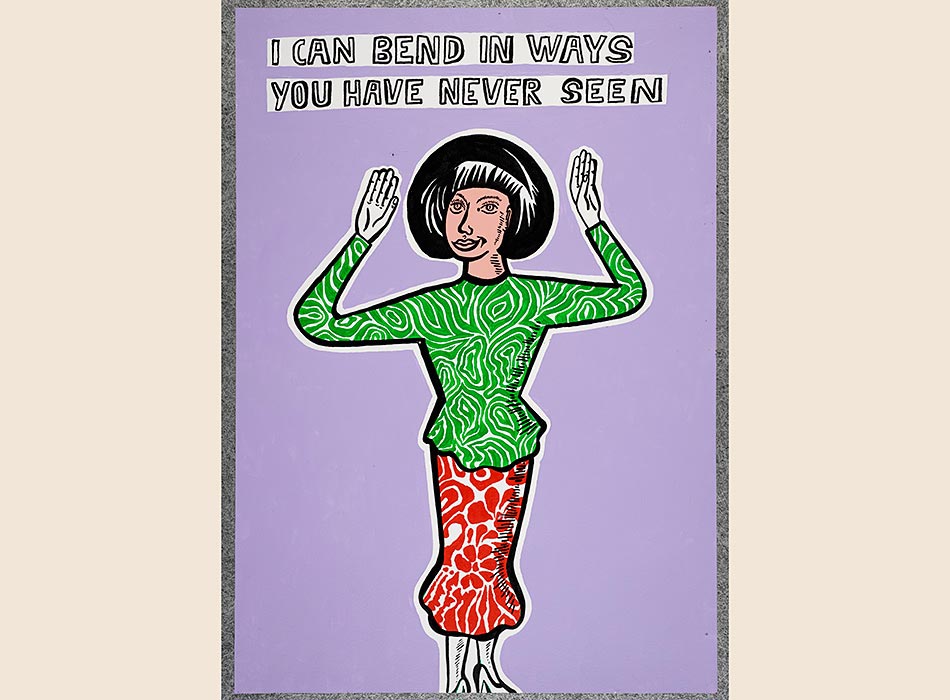

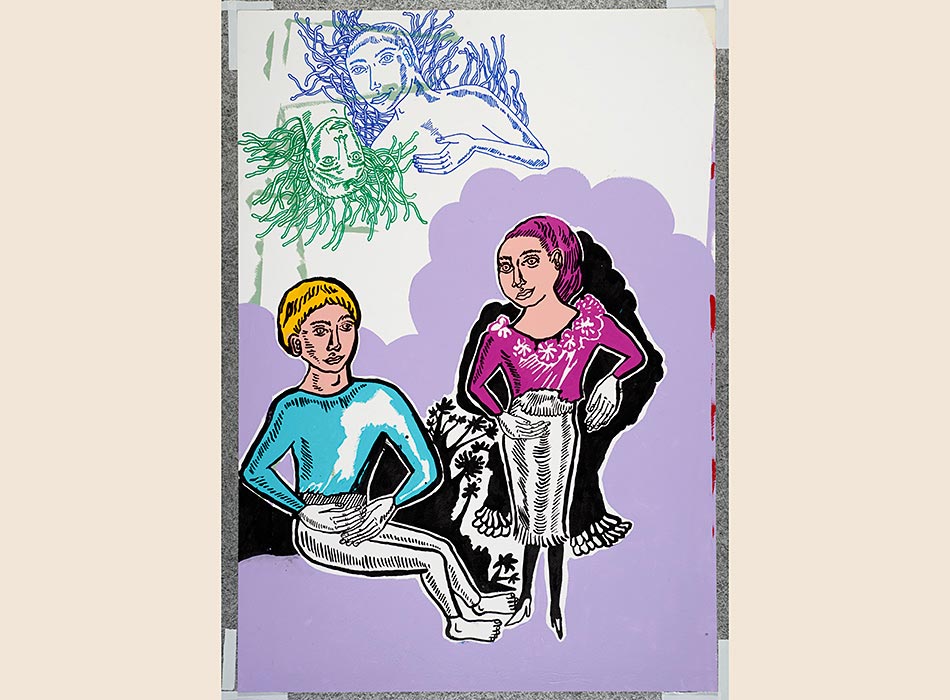

Boys Who Love Boys & Girls Who Love Girls Collection 2018

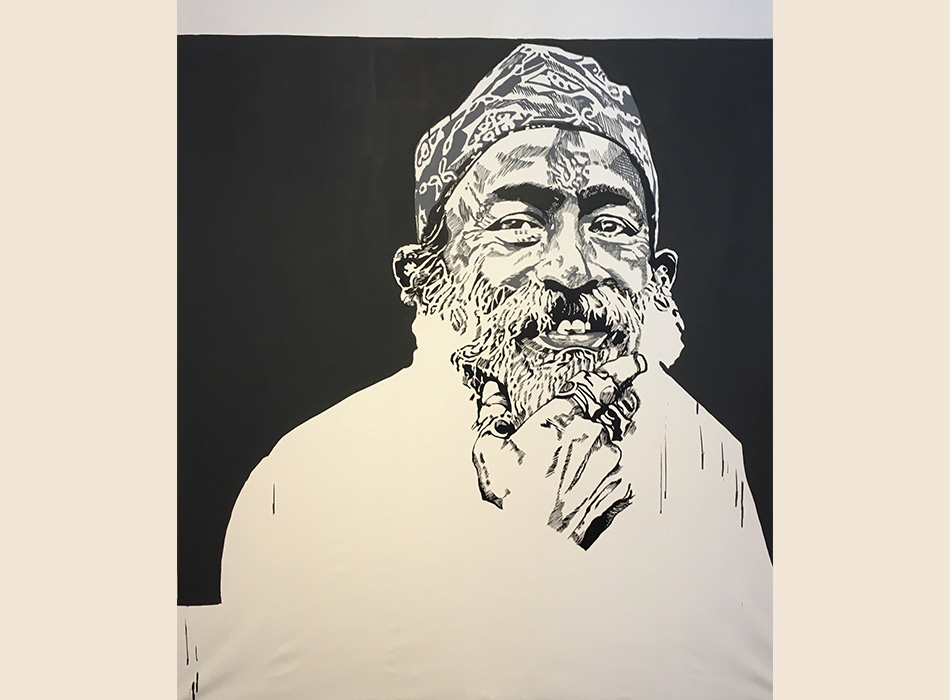

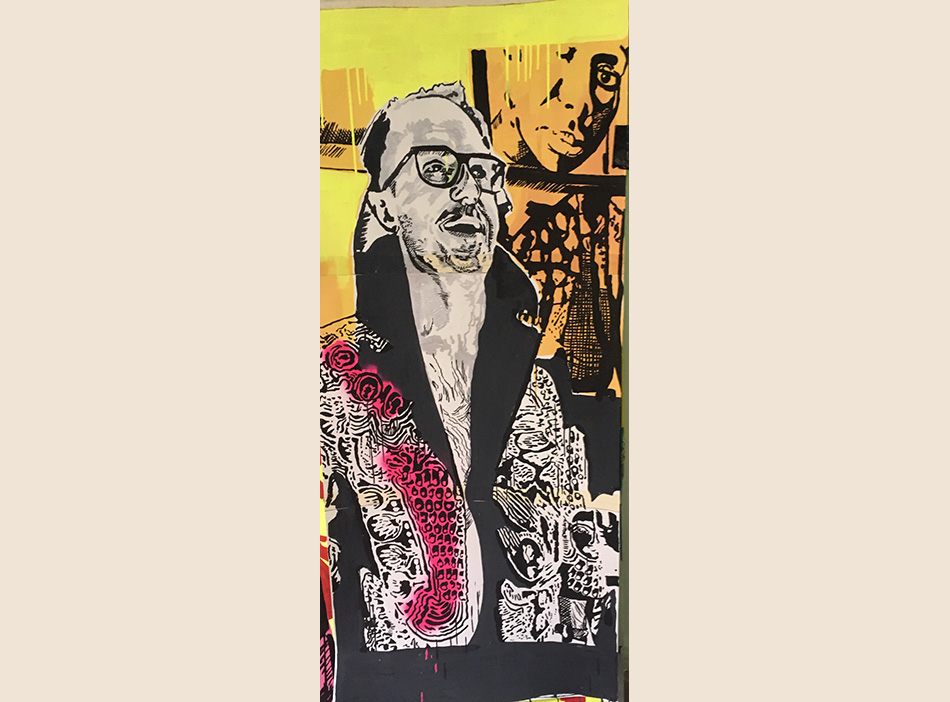

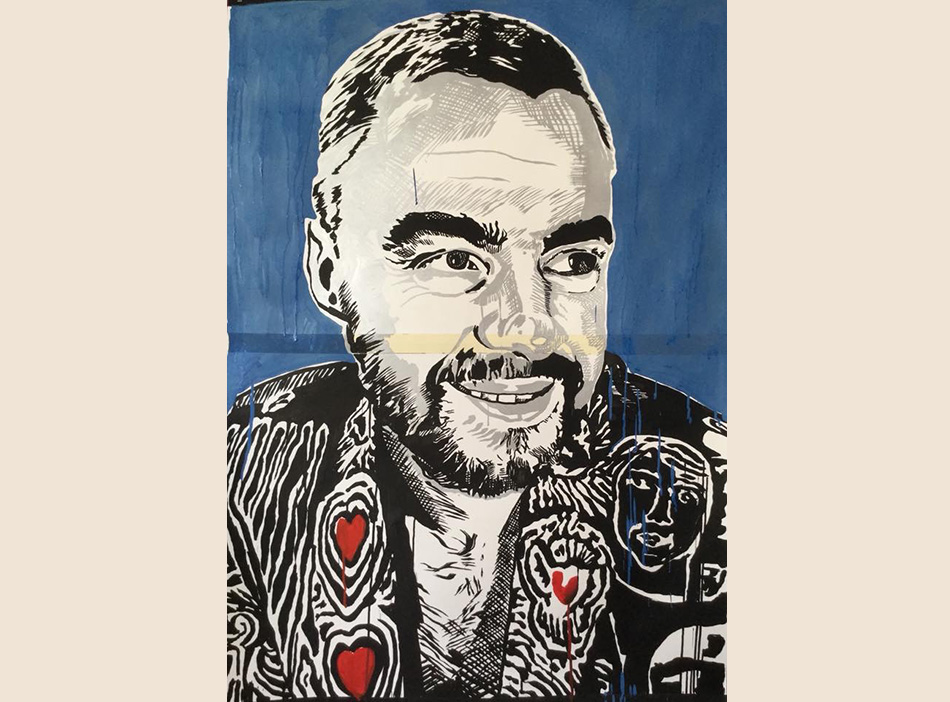

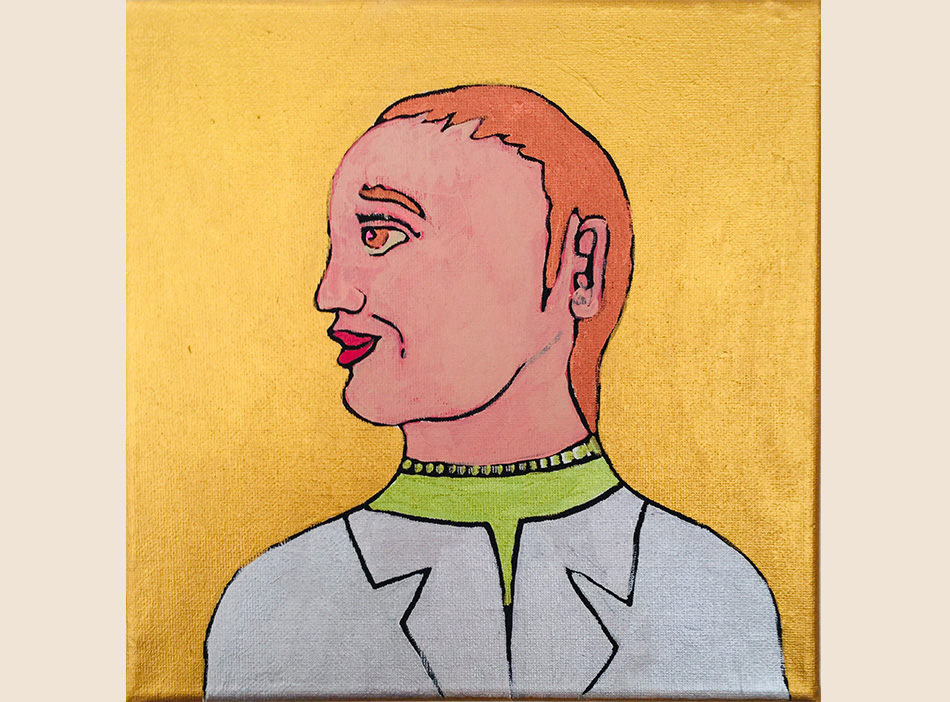

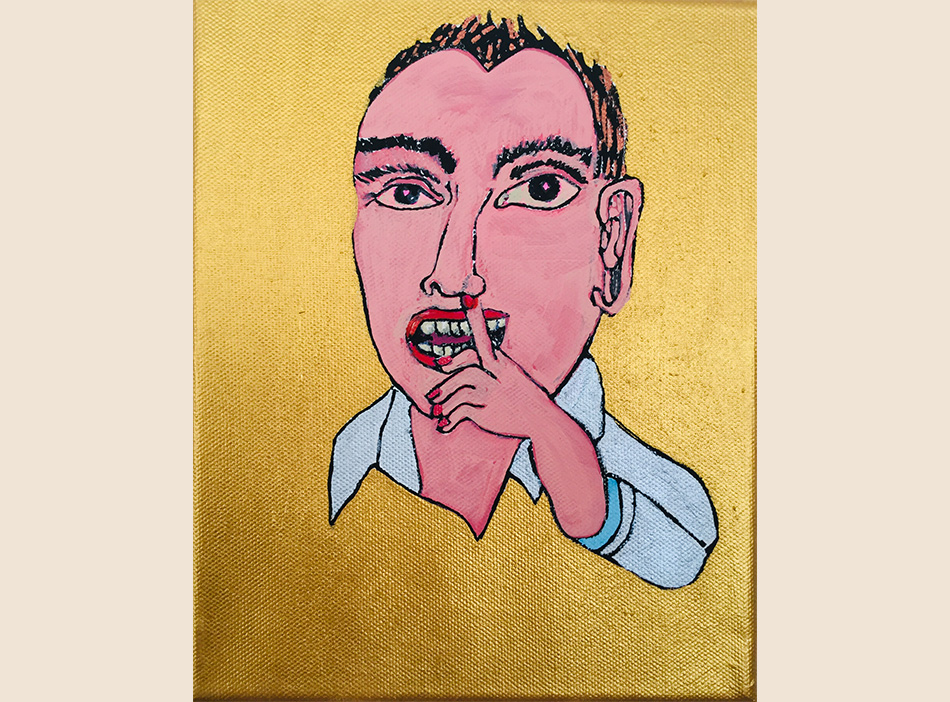

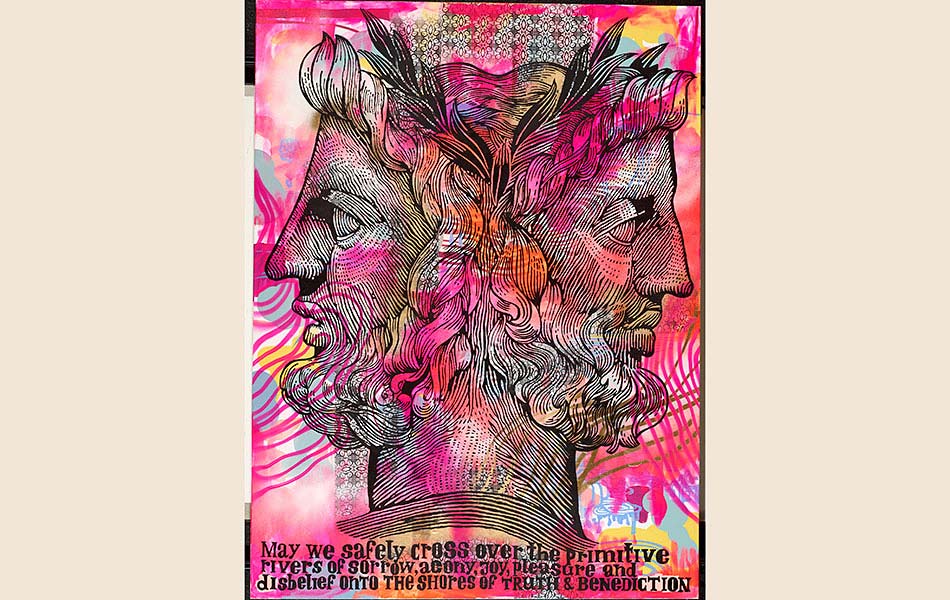

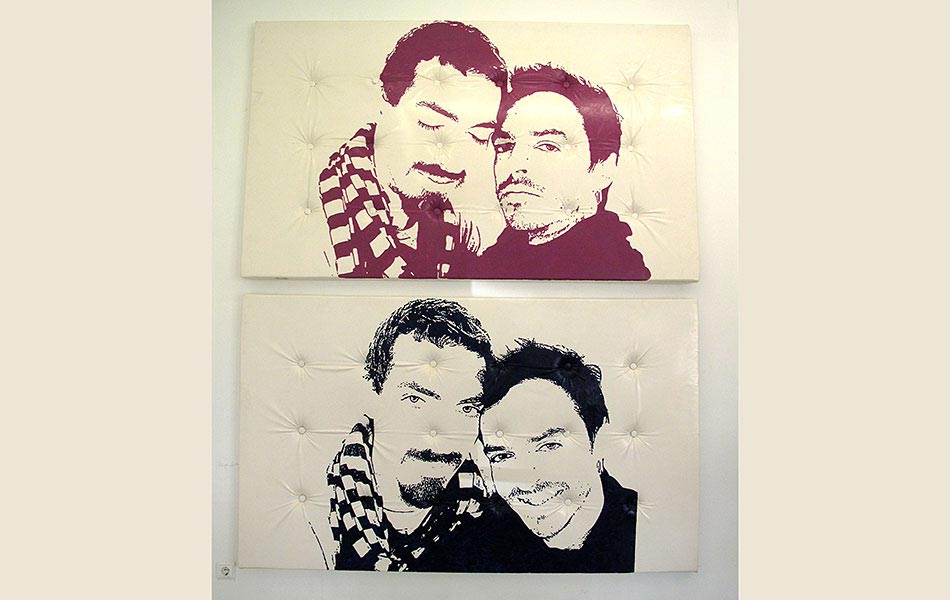

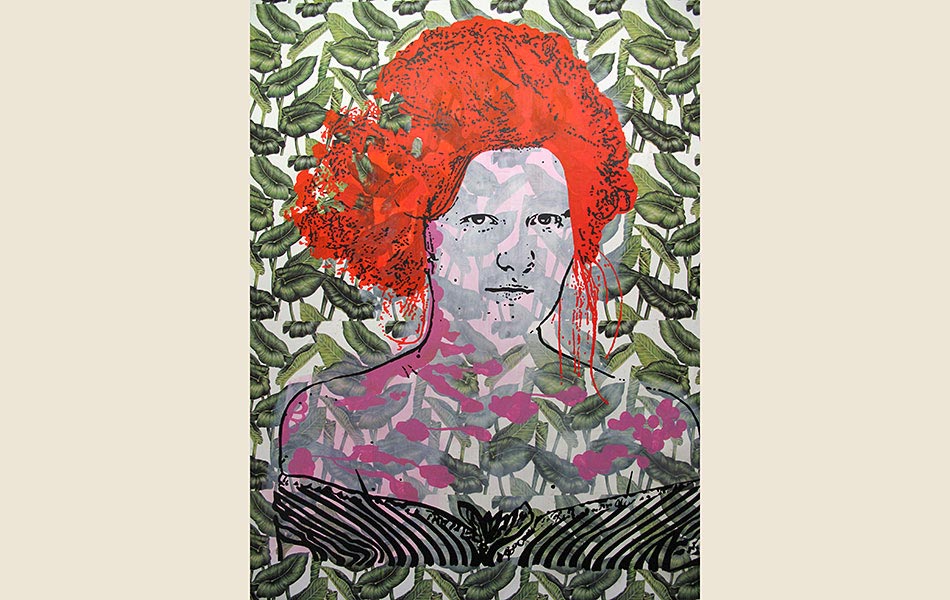

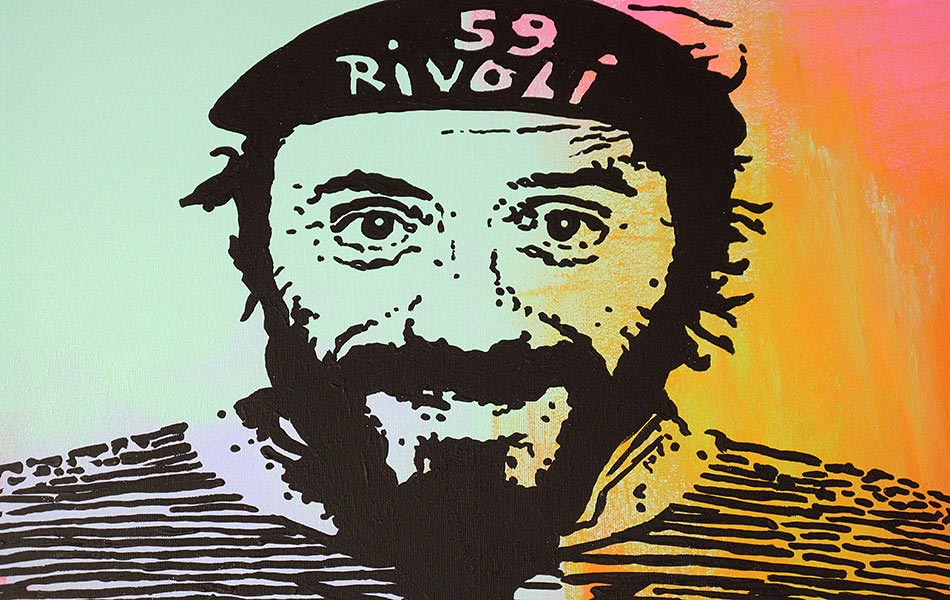

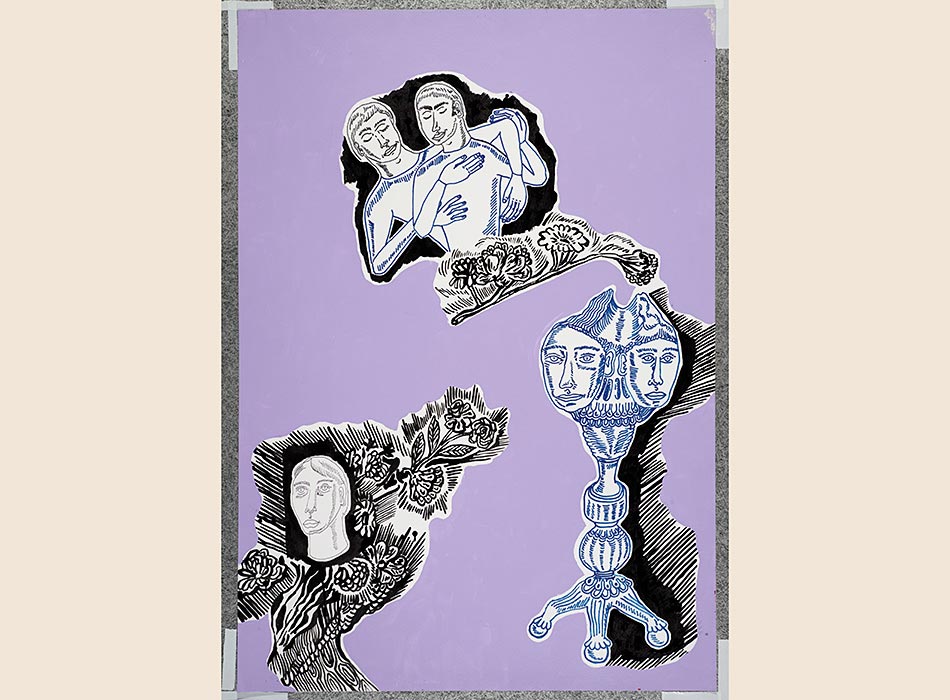

Portraits 2018

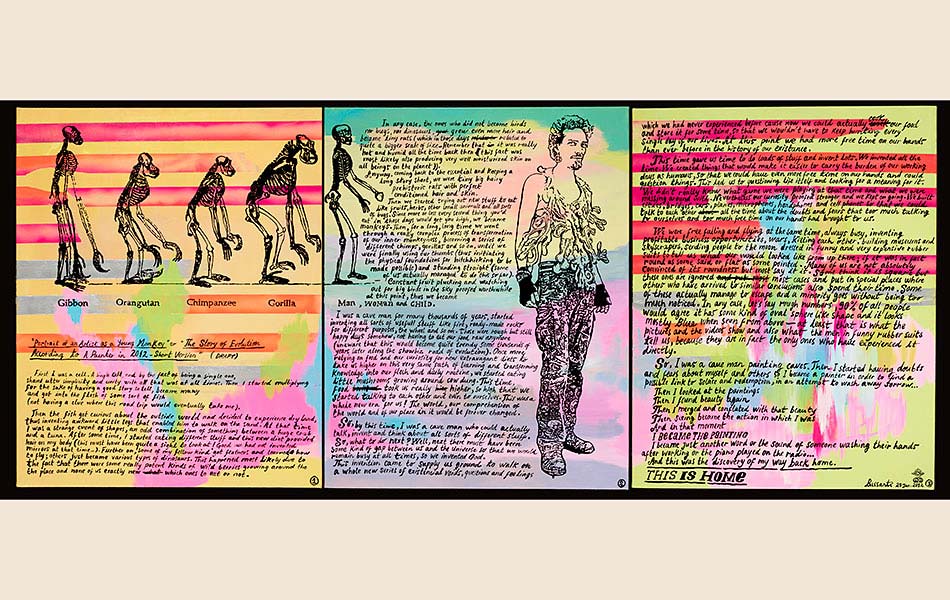

#EVIVAOTRAUMA – Luisa Soeiro & Bassanti 2017 / 2018

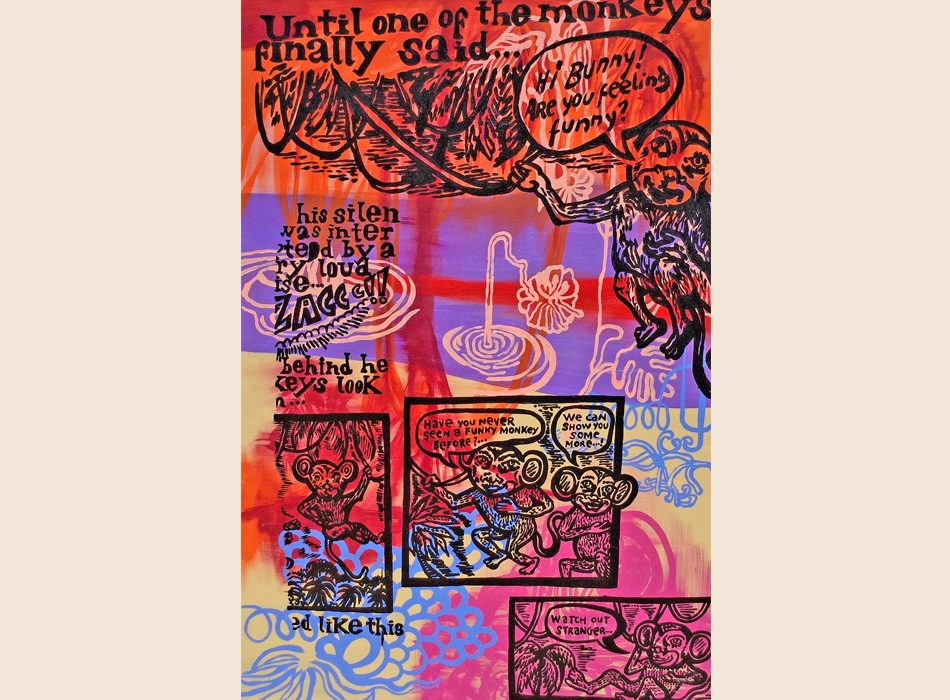

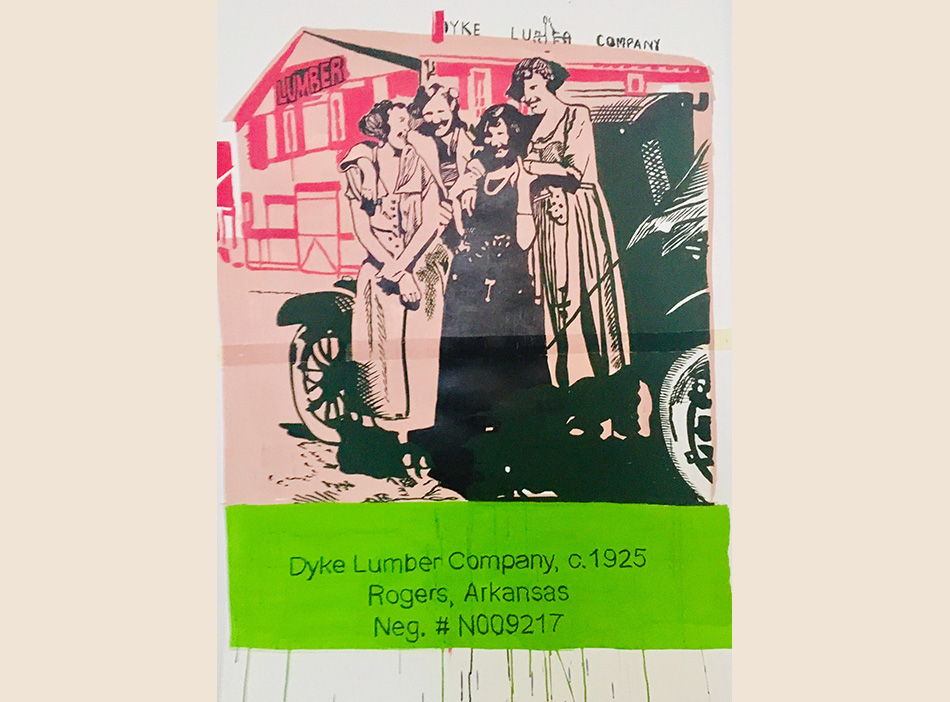

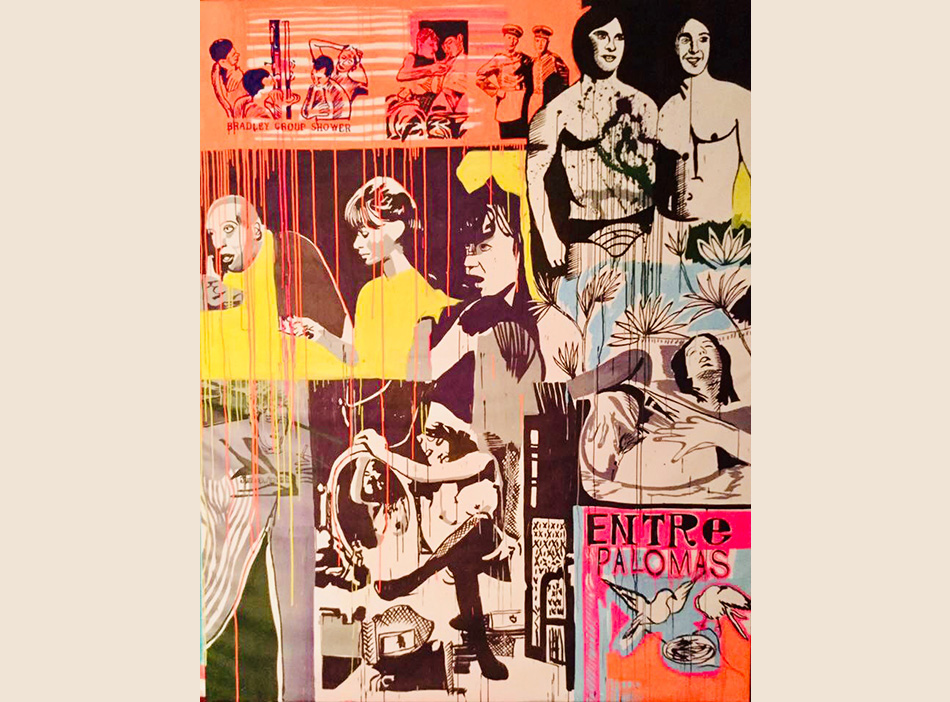

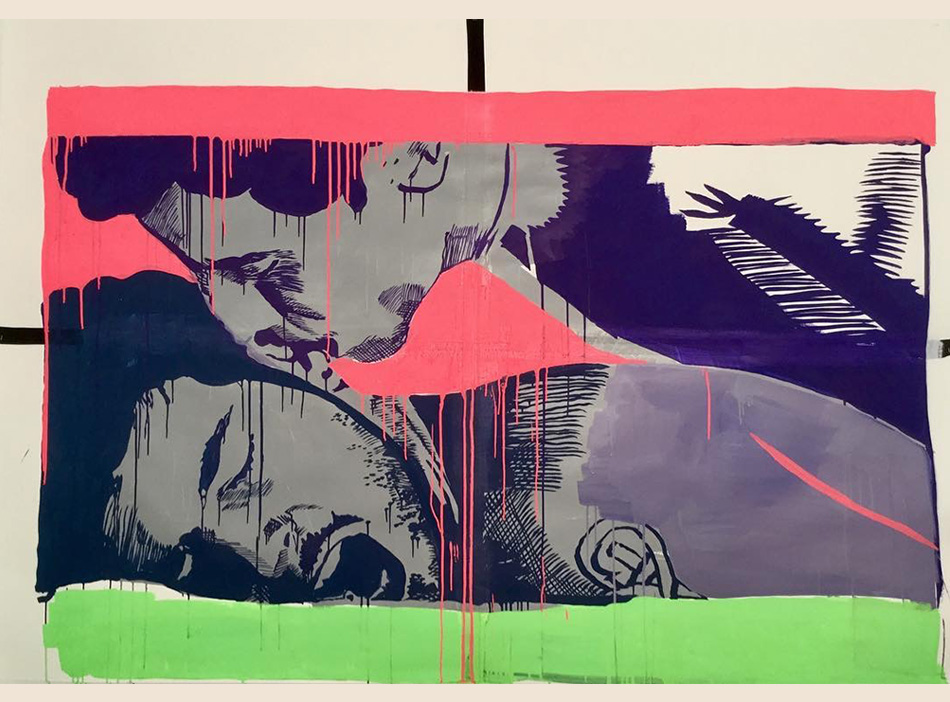

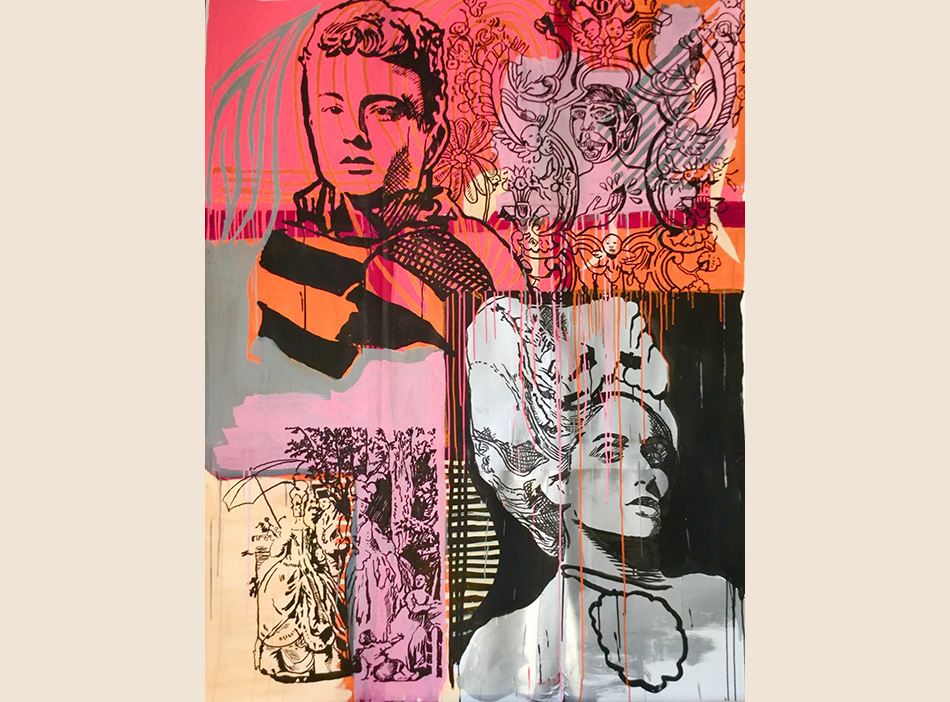

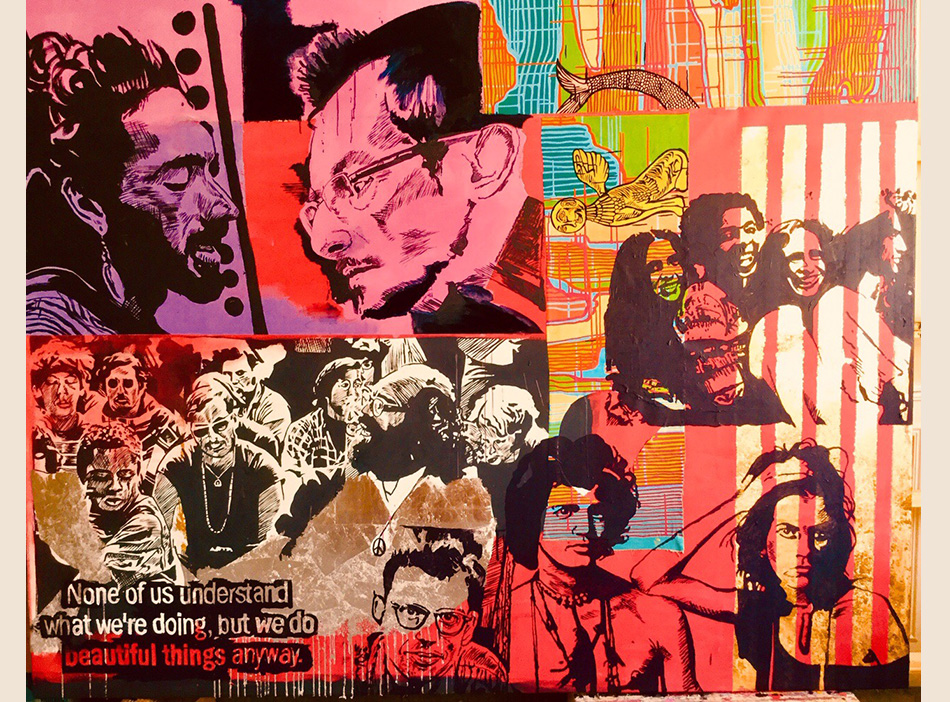

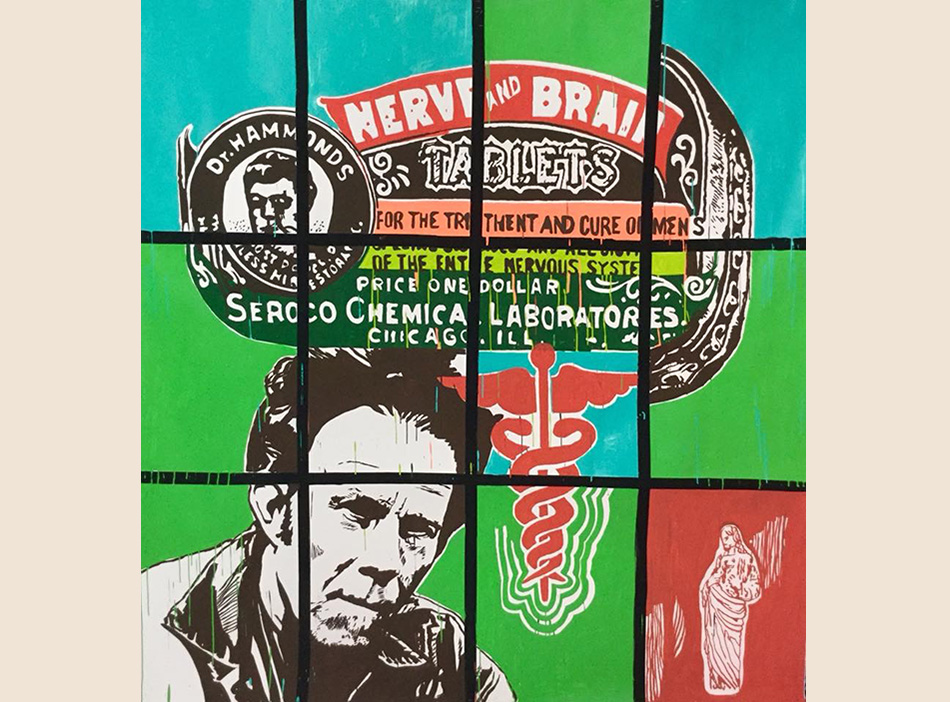

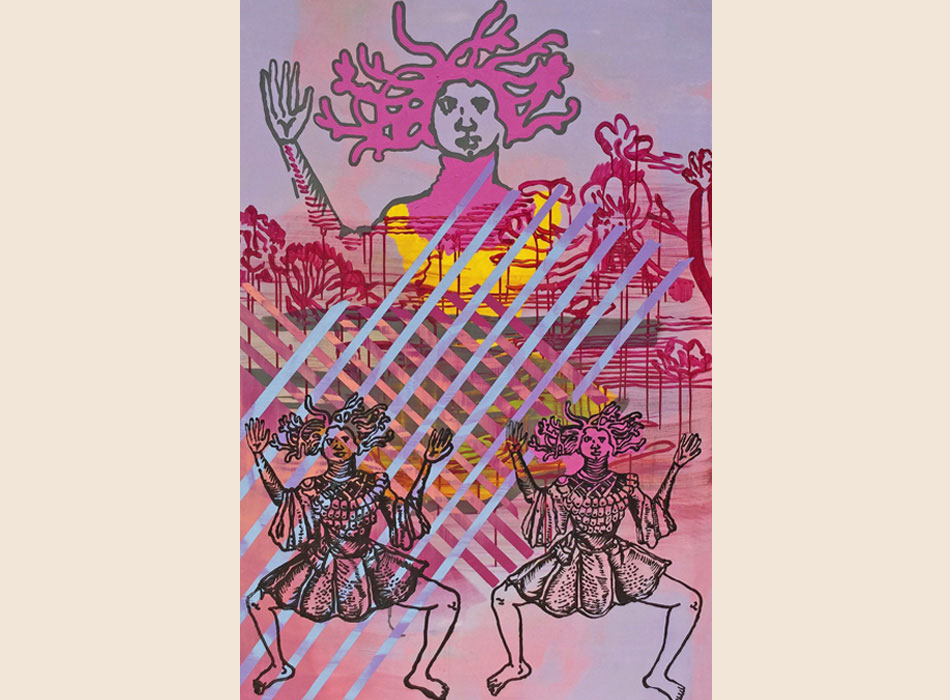

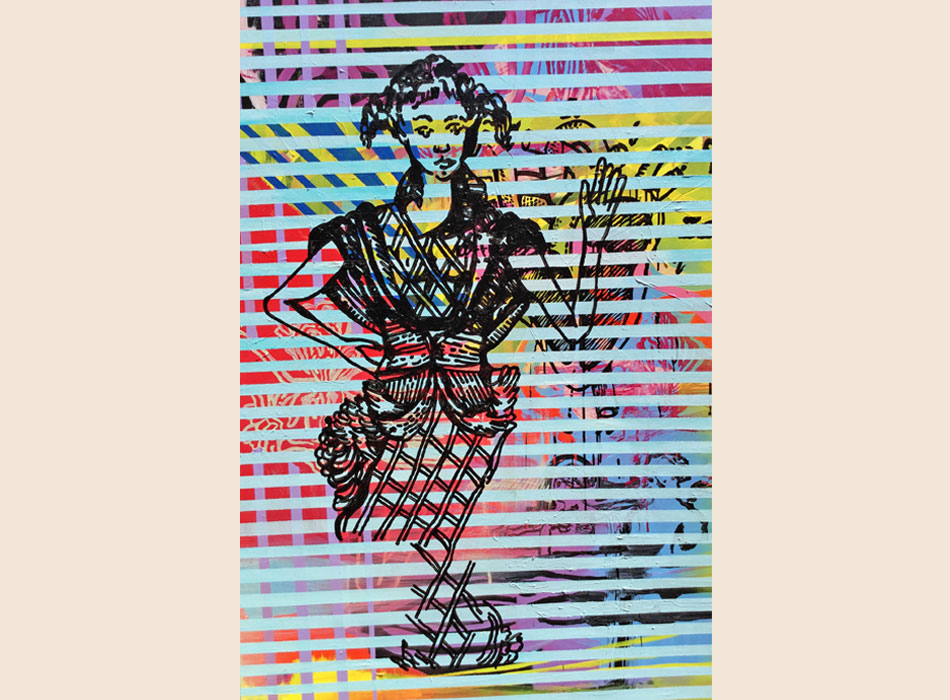

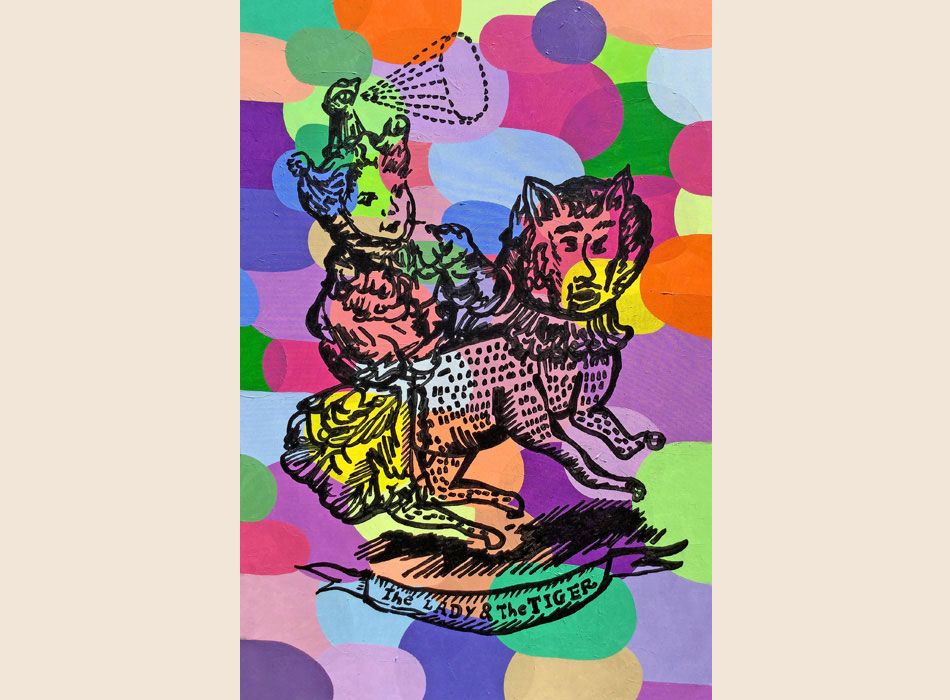

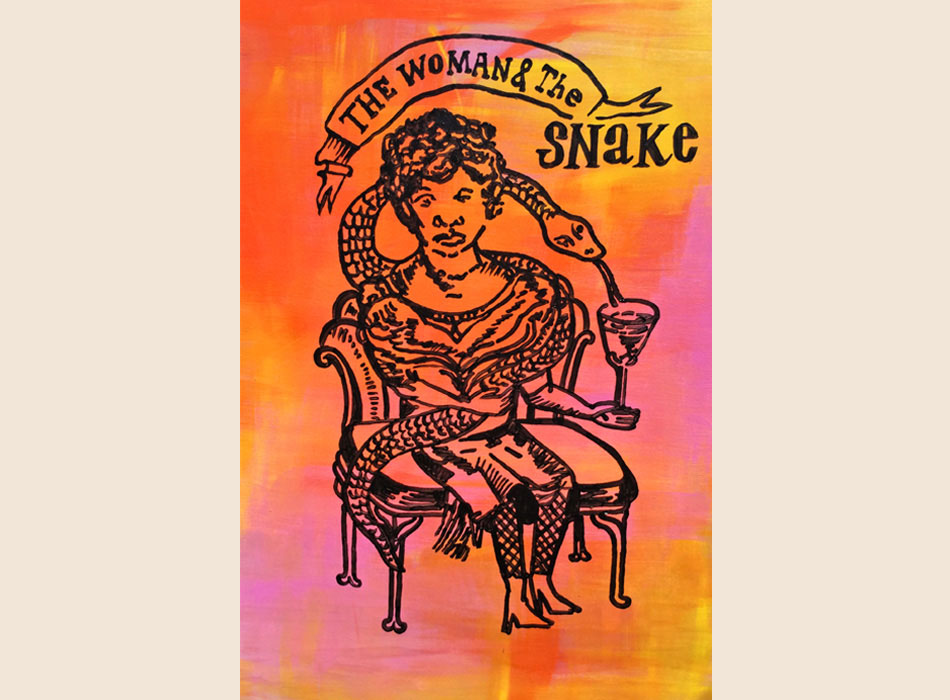

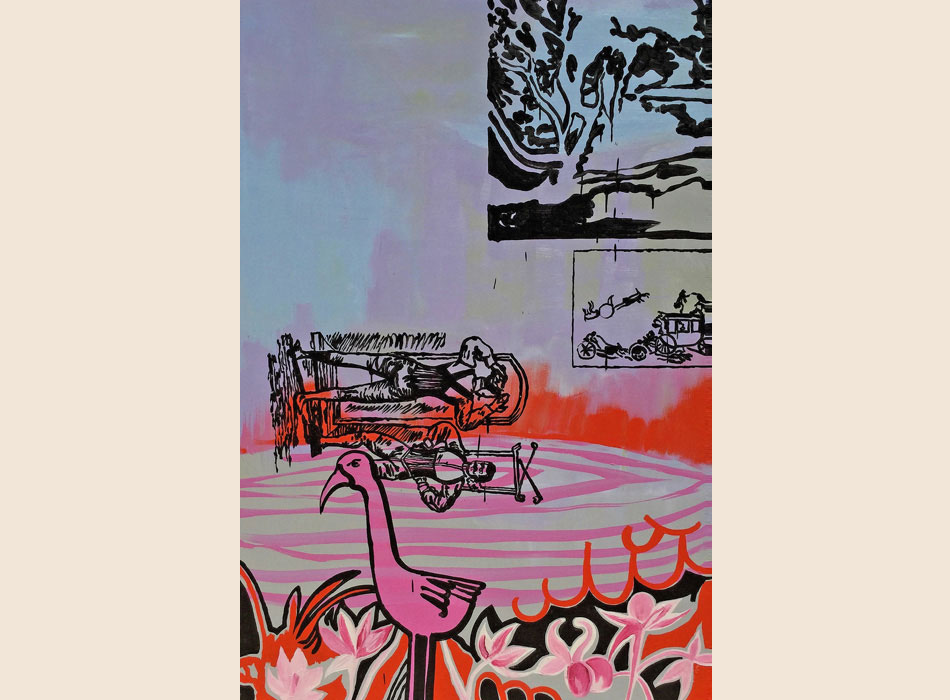

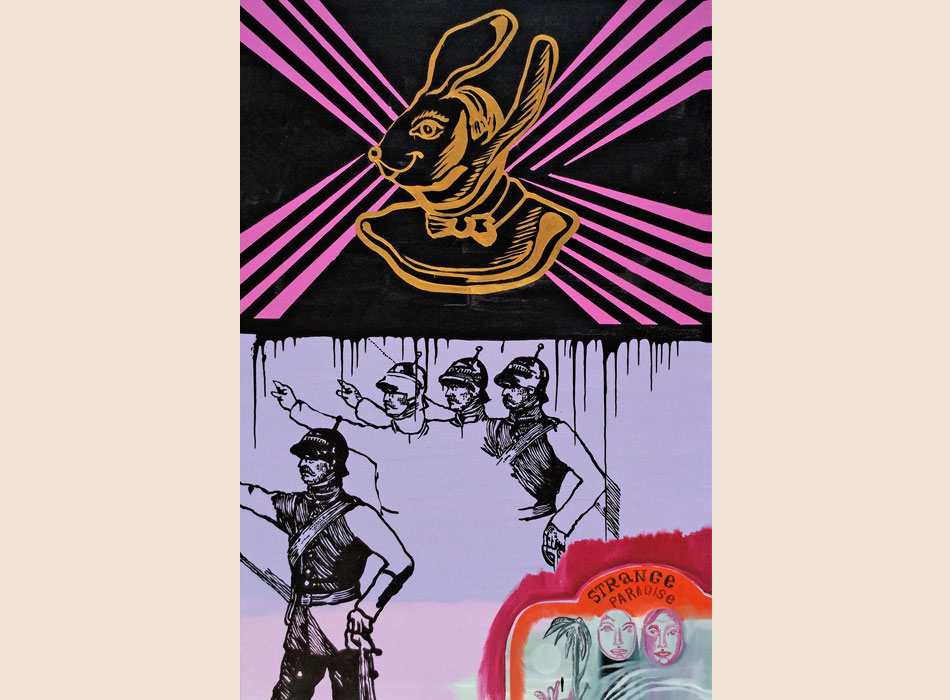

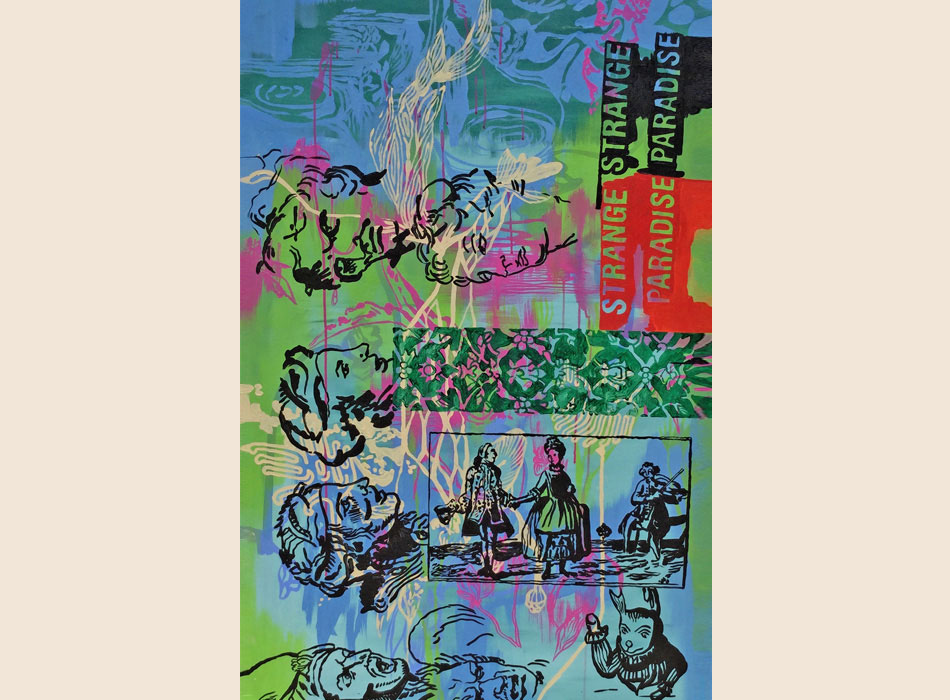

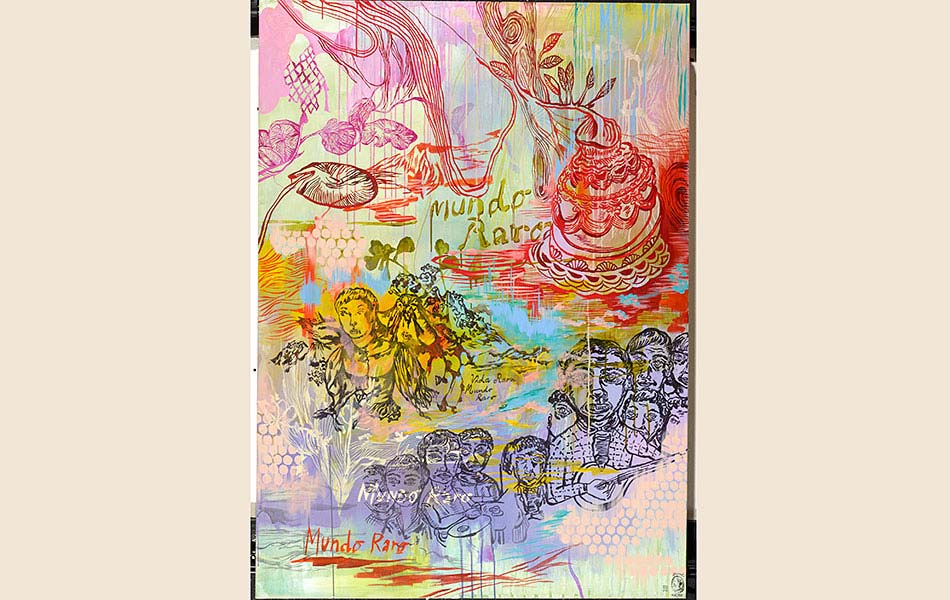

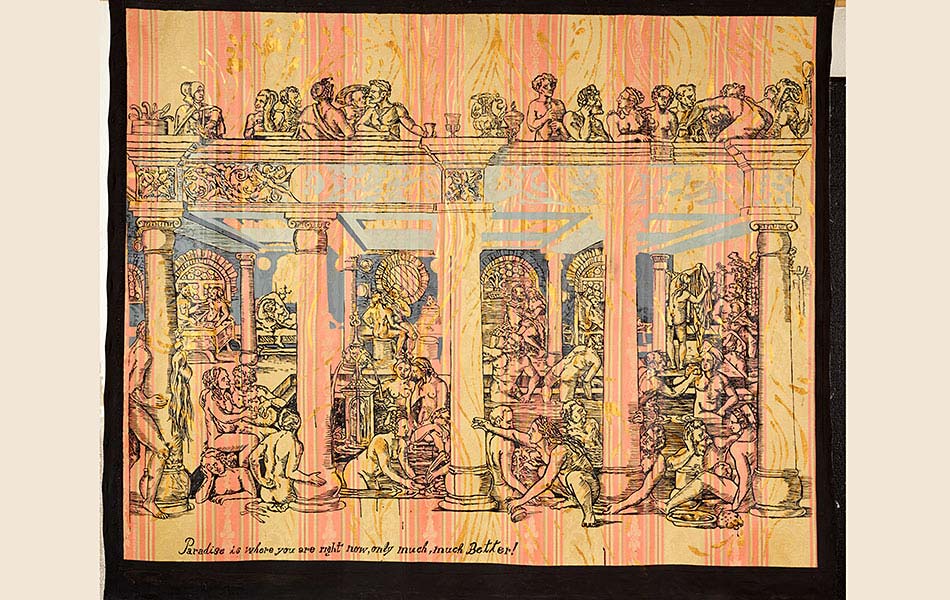

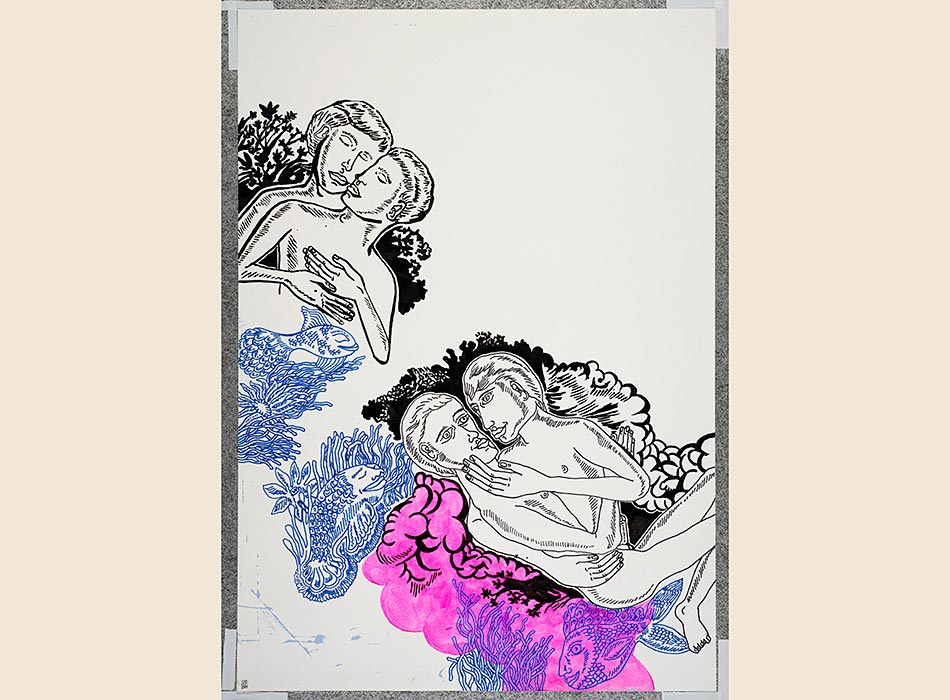

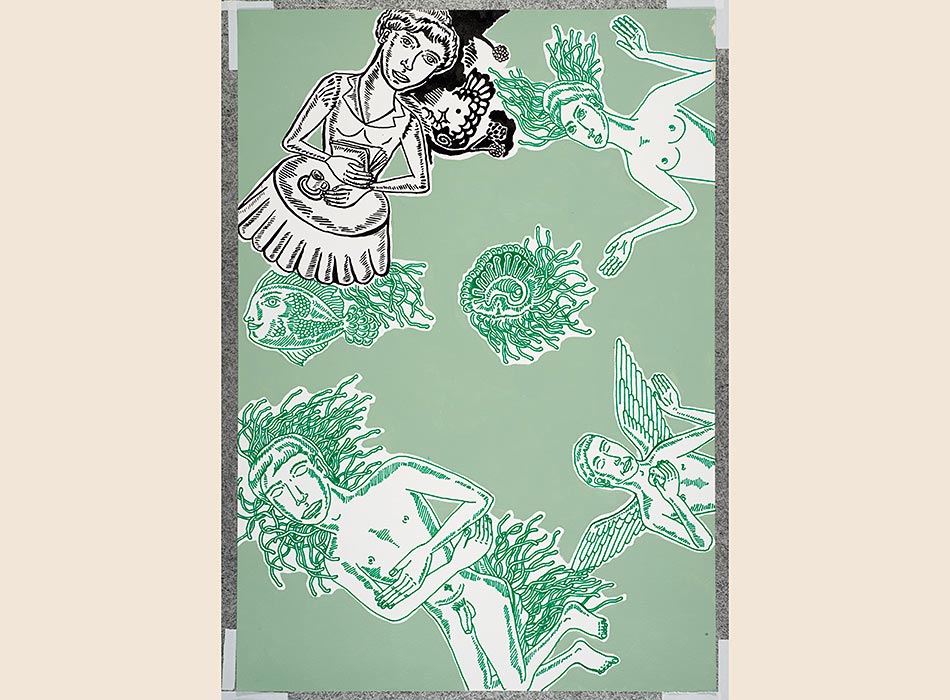

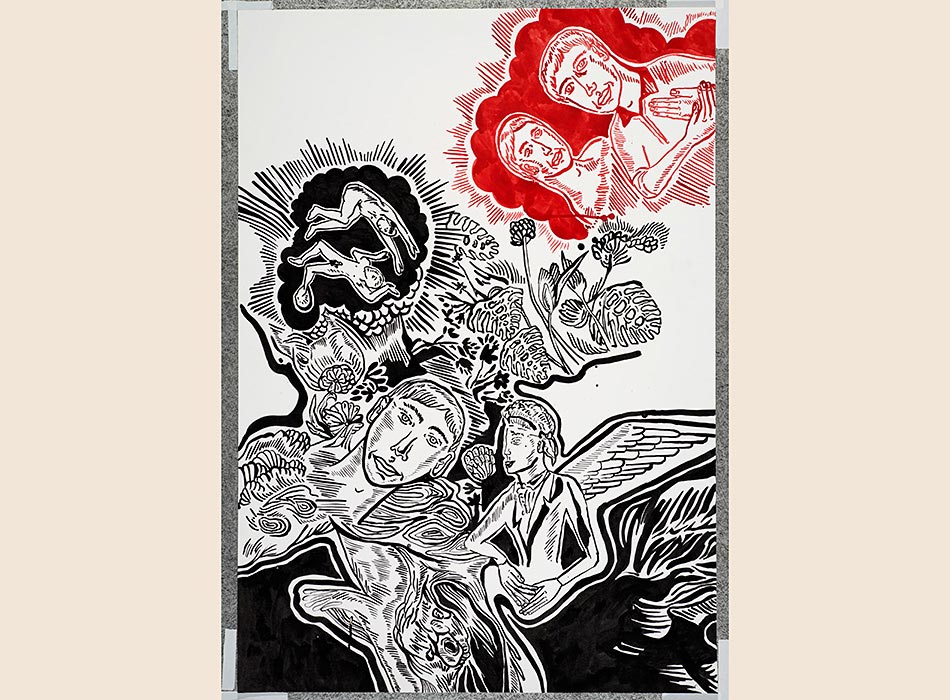

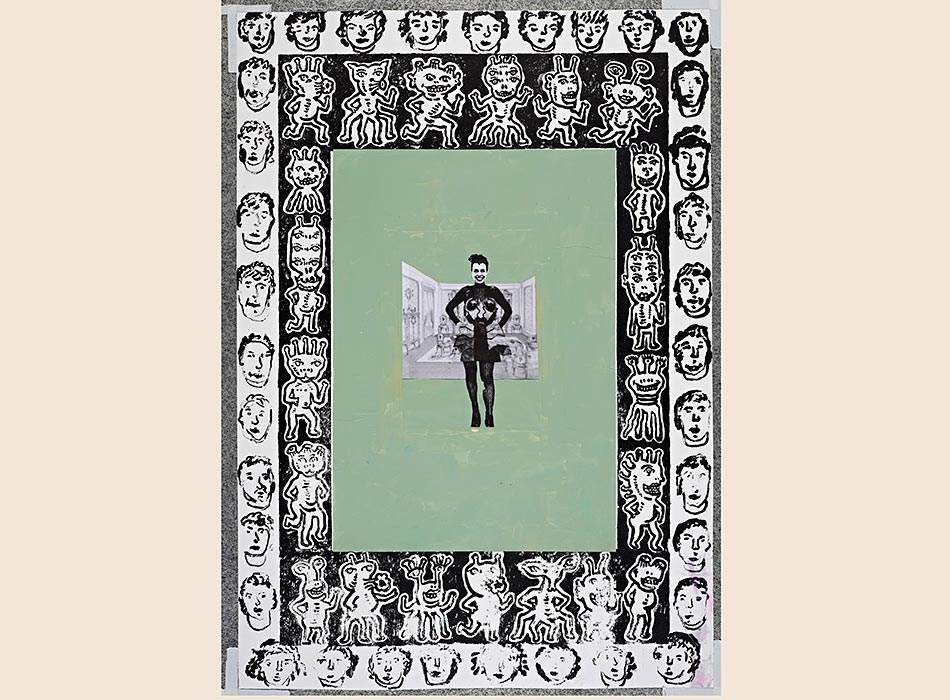

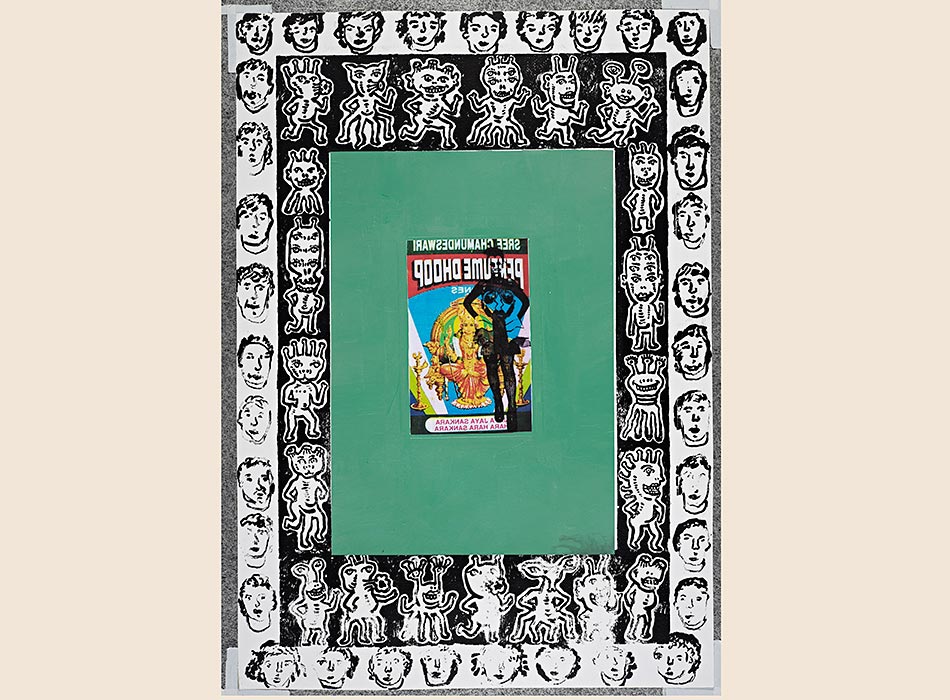

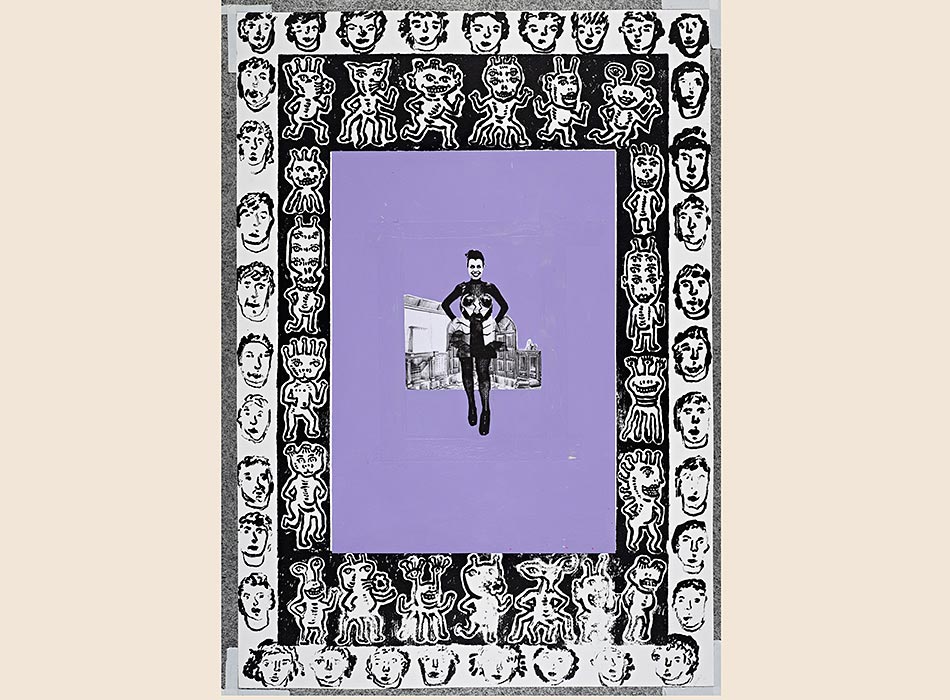

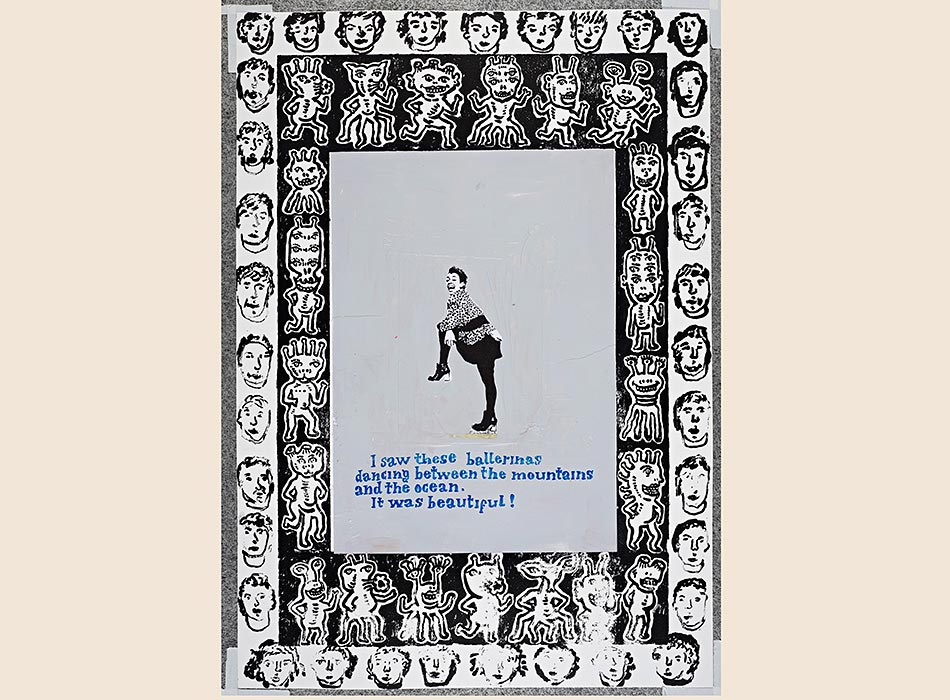

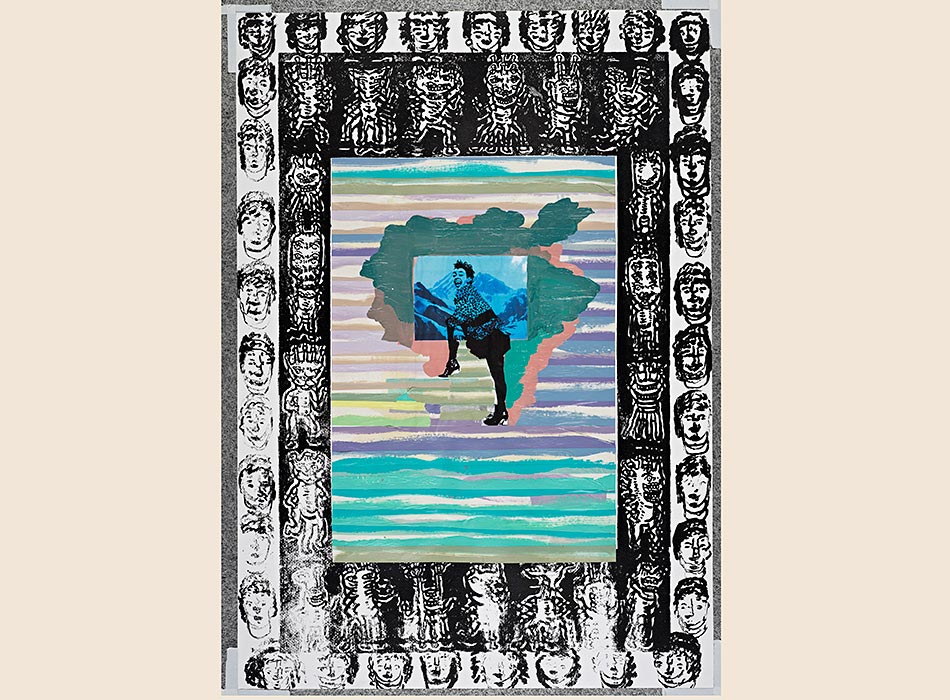

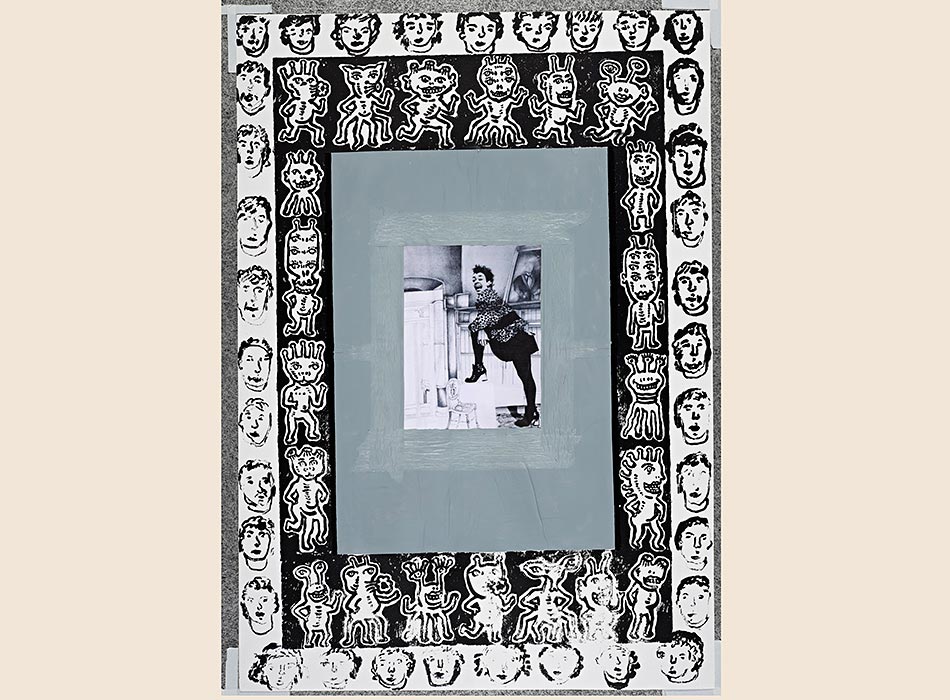

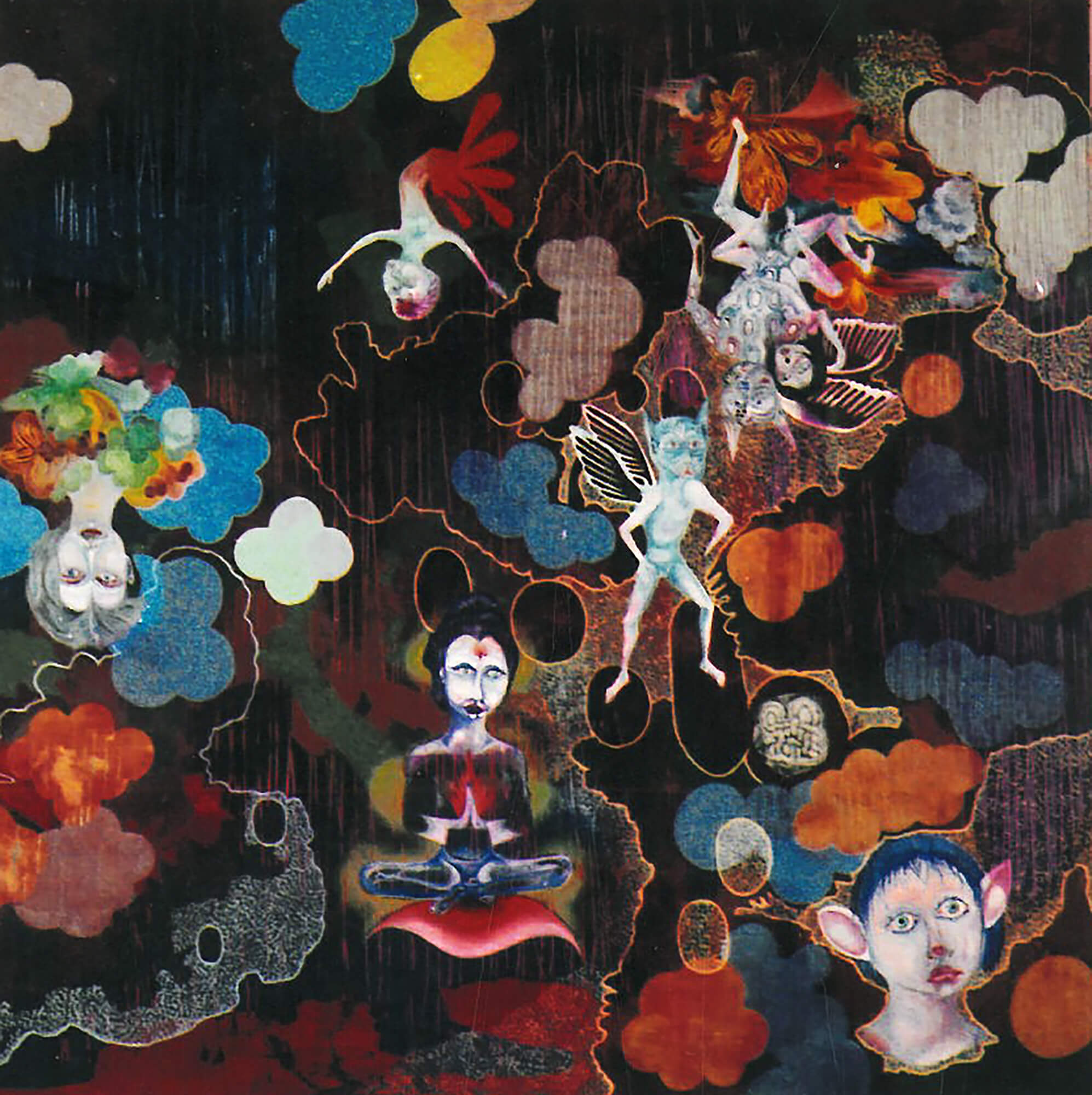

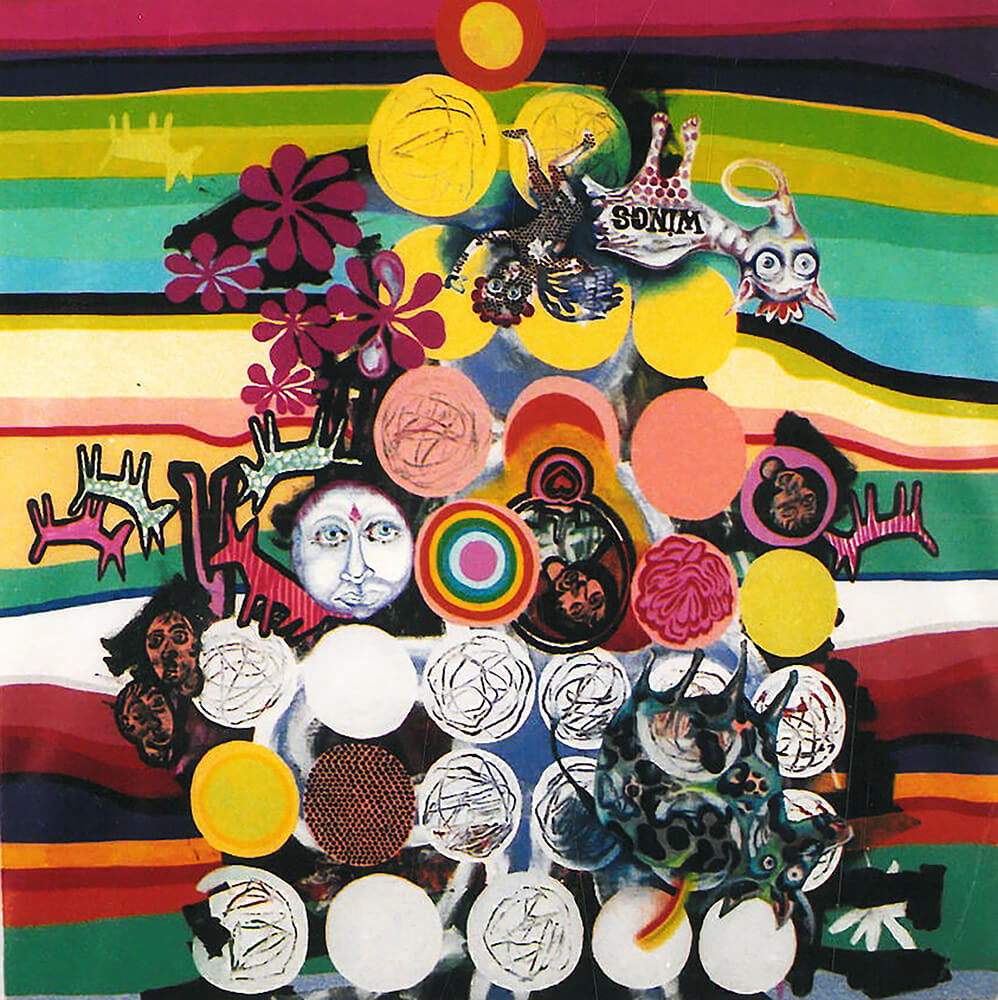

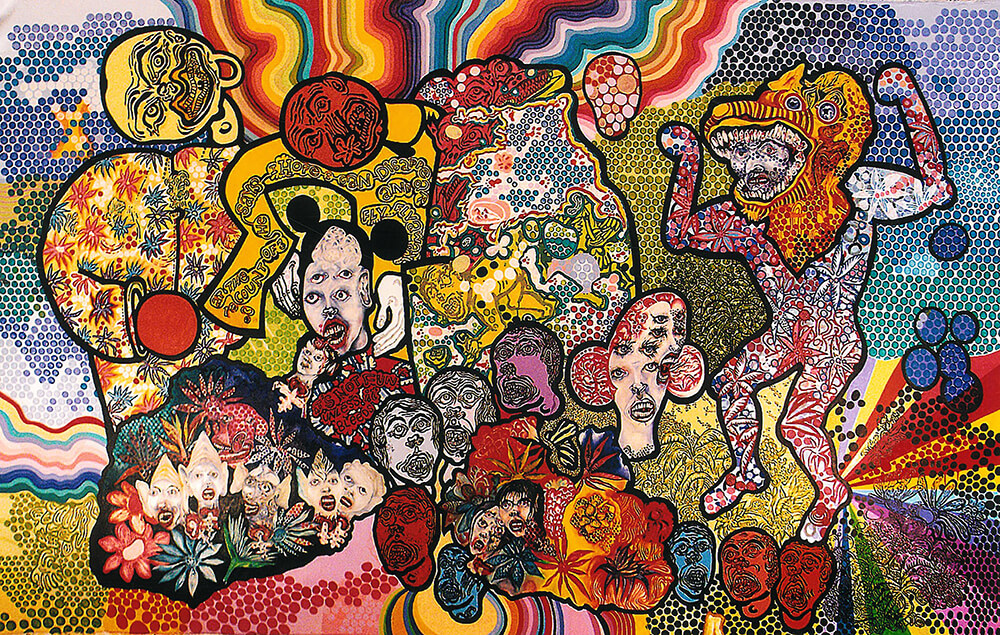

Strange Paradise Series, 2014/2015

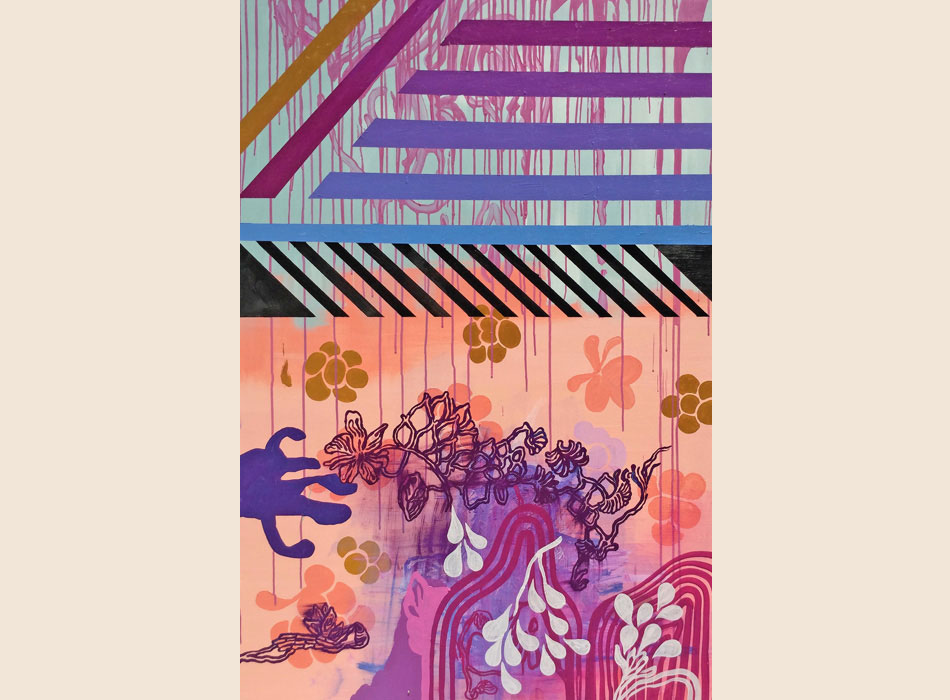

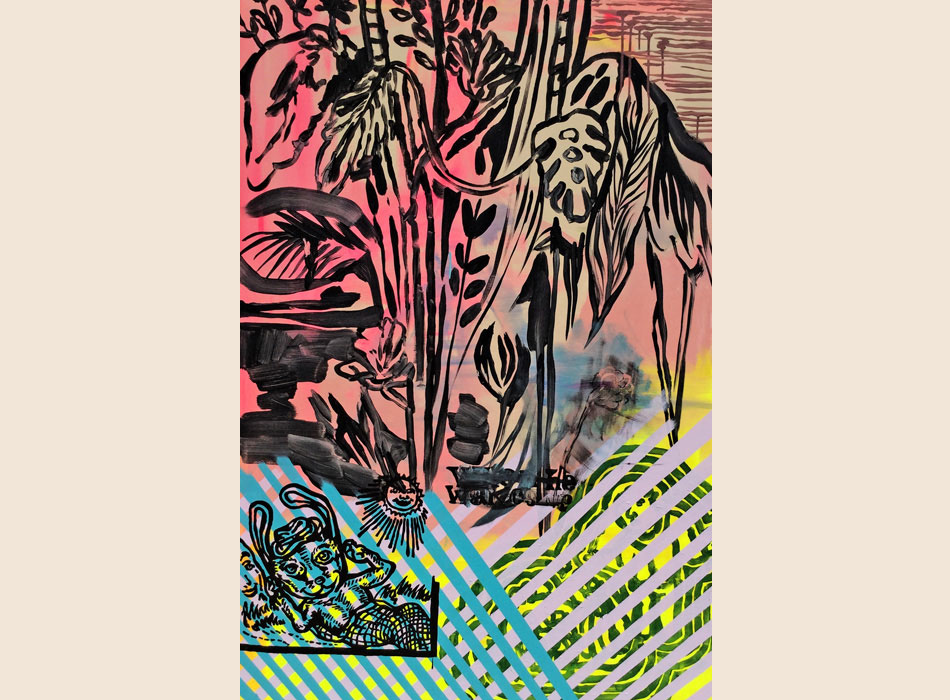

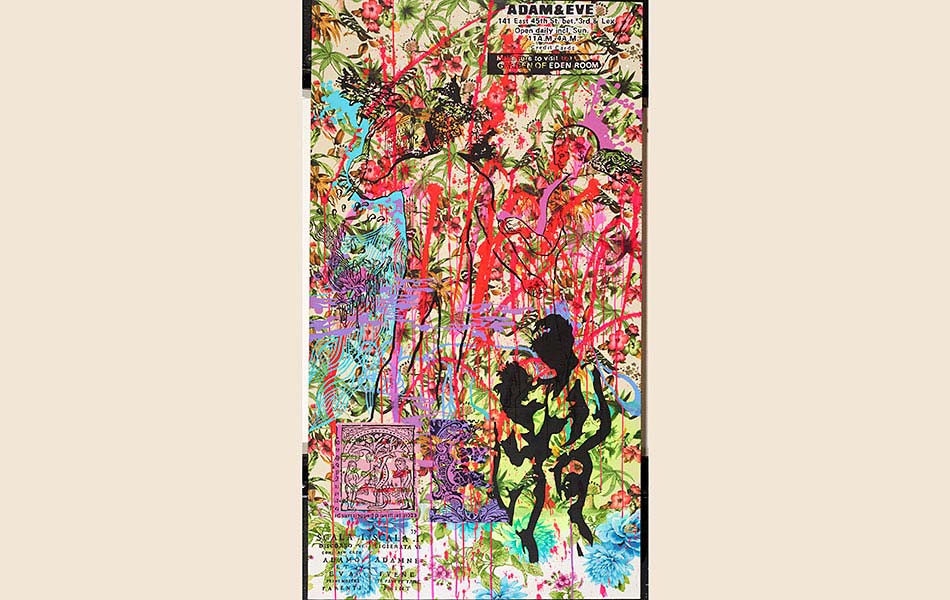

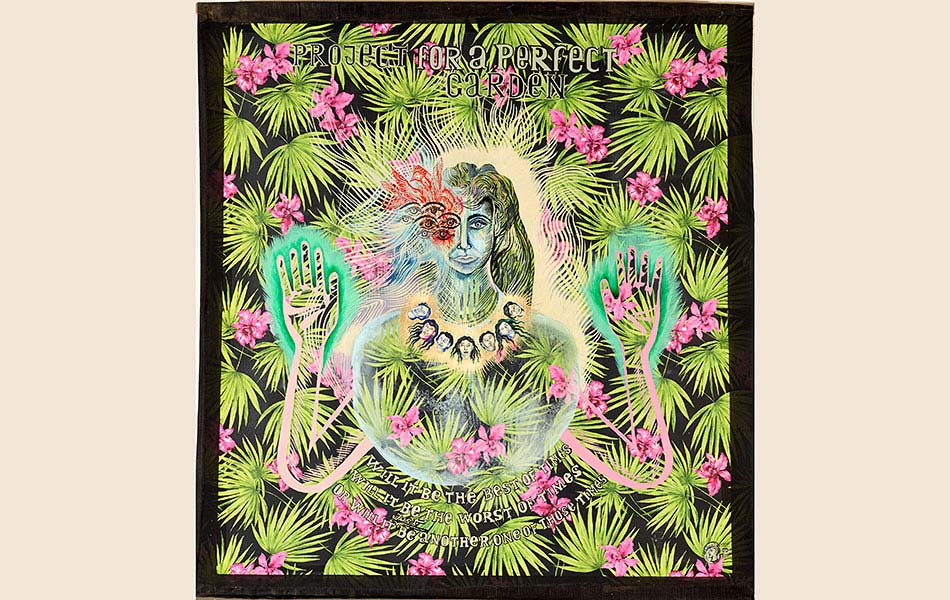

Project for a Perfect Garden, 2012

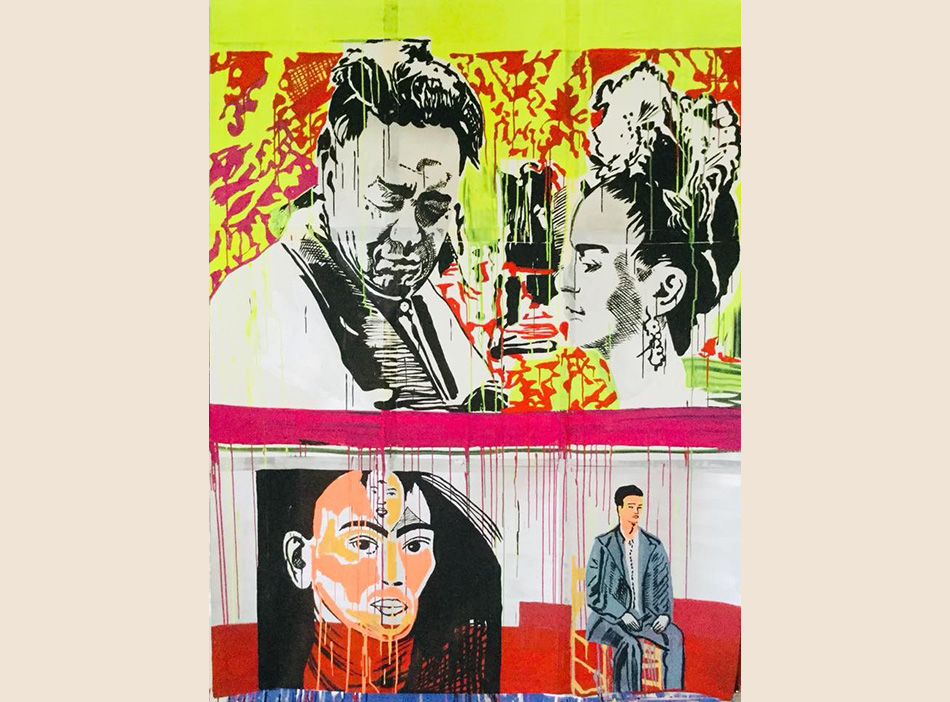

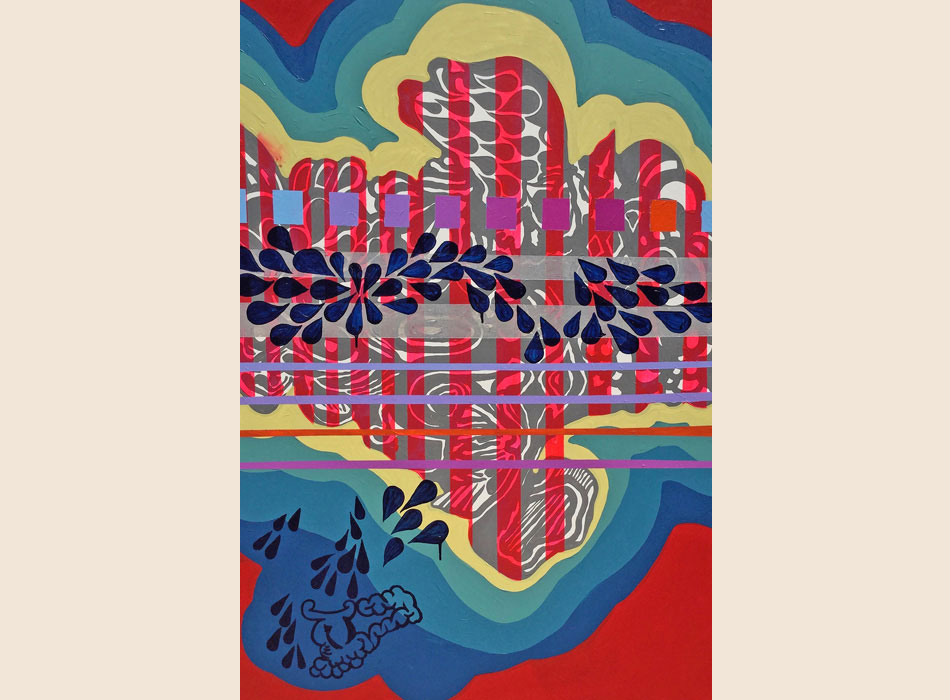

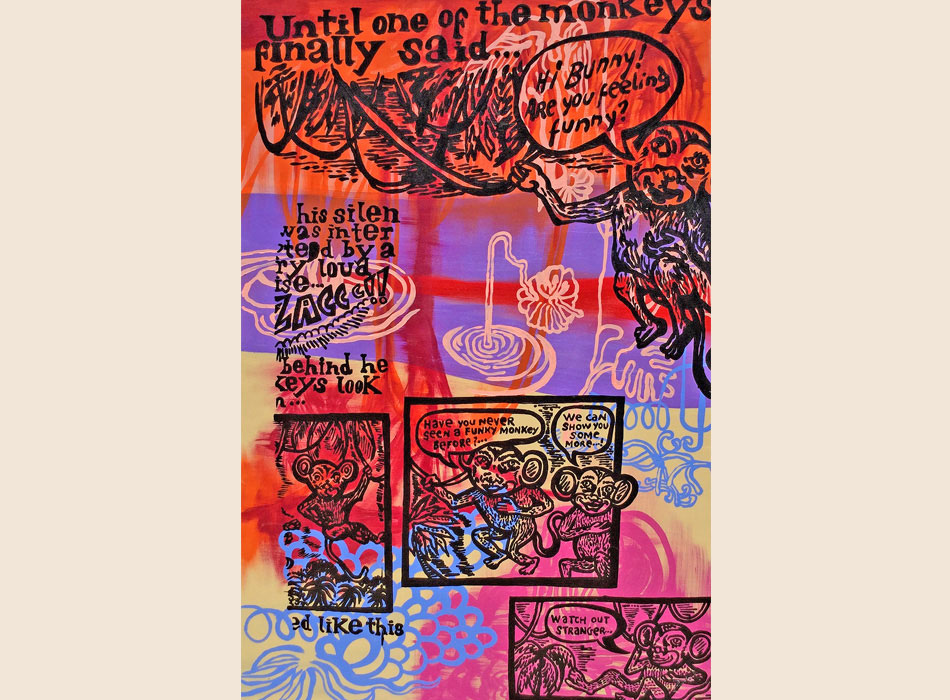

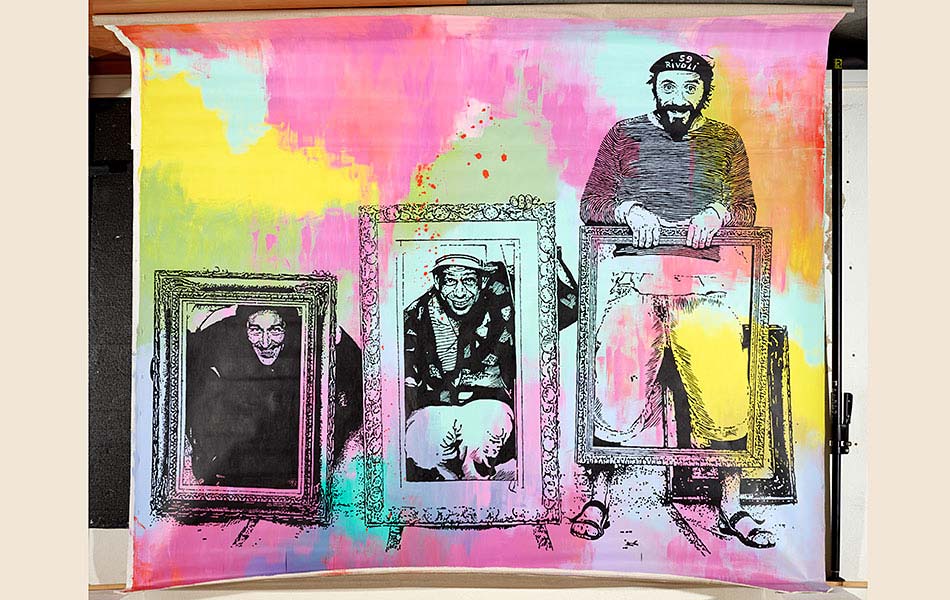

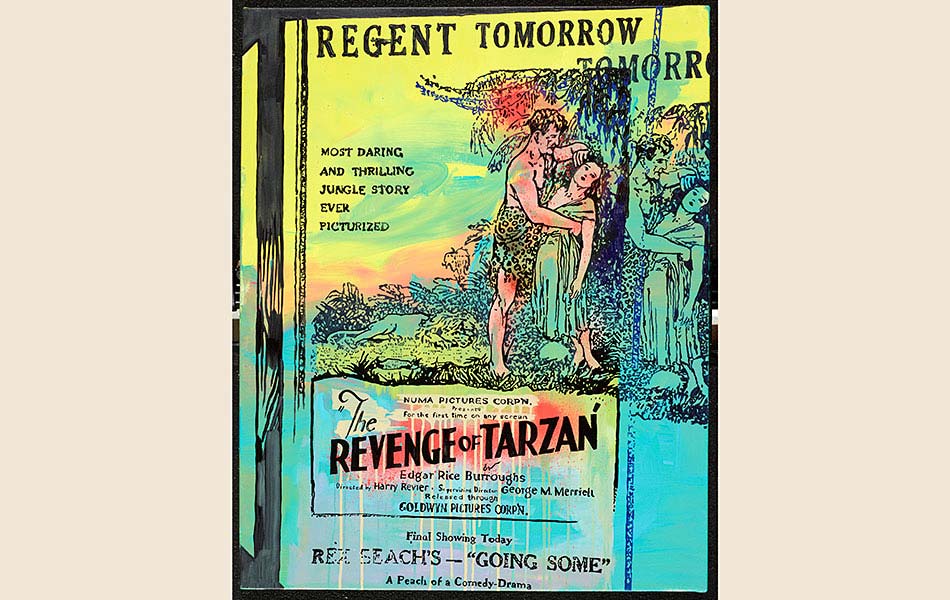

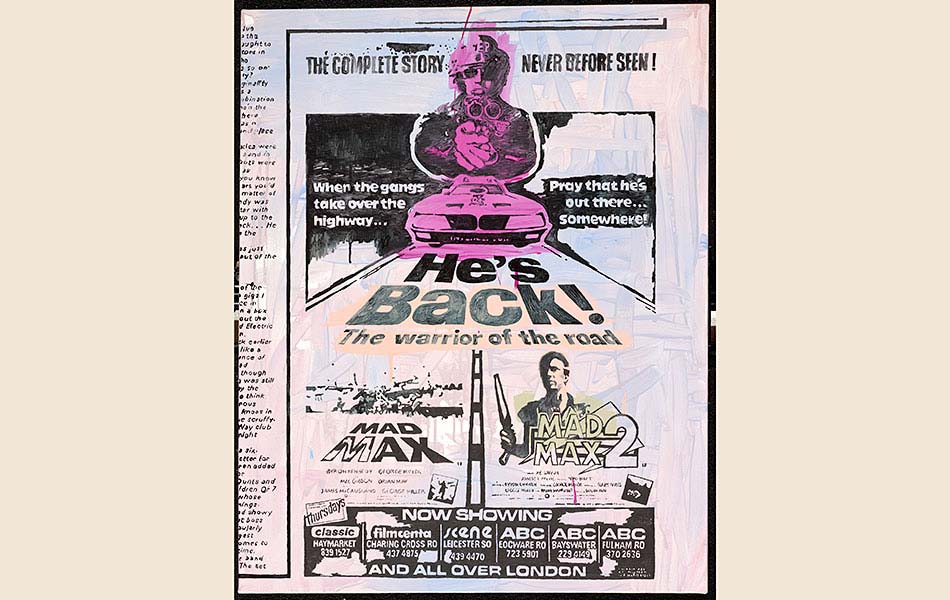

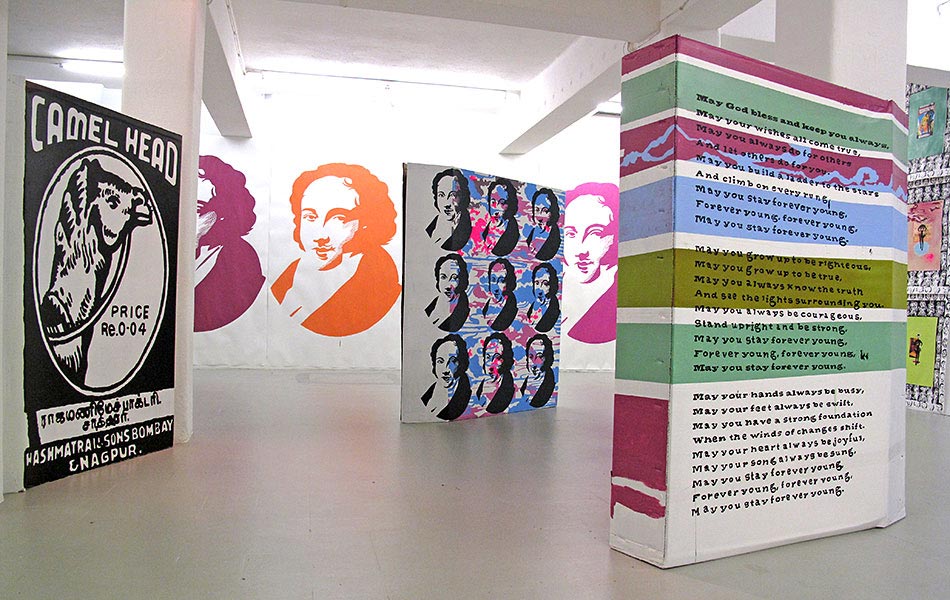

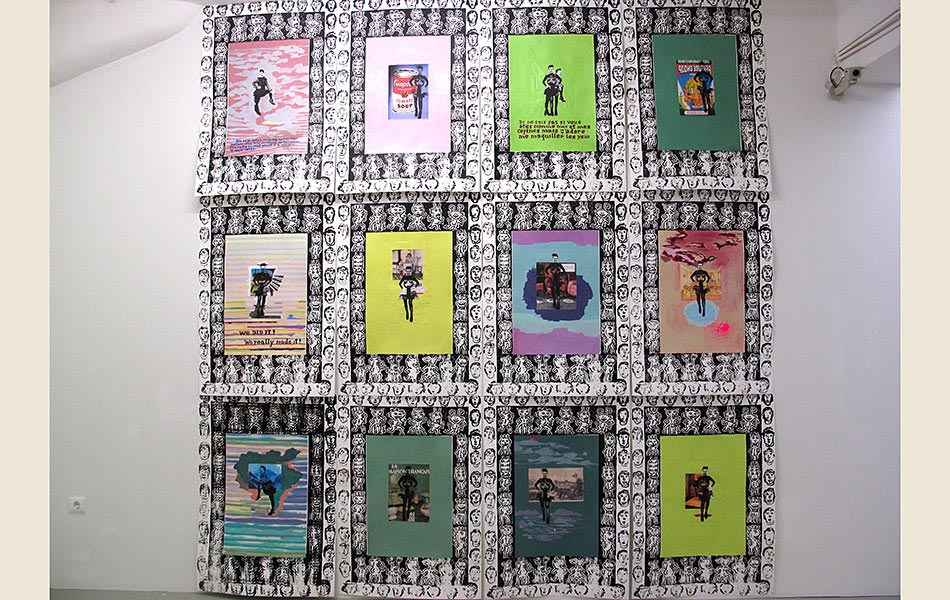

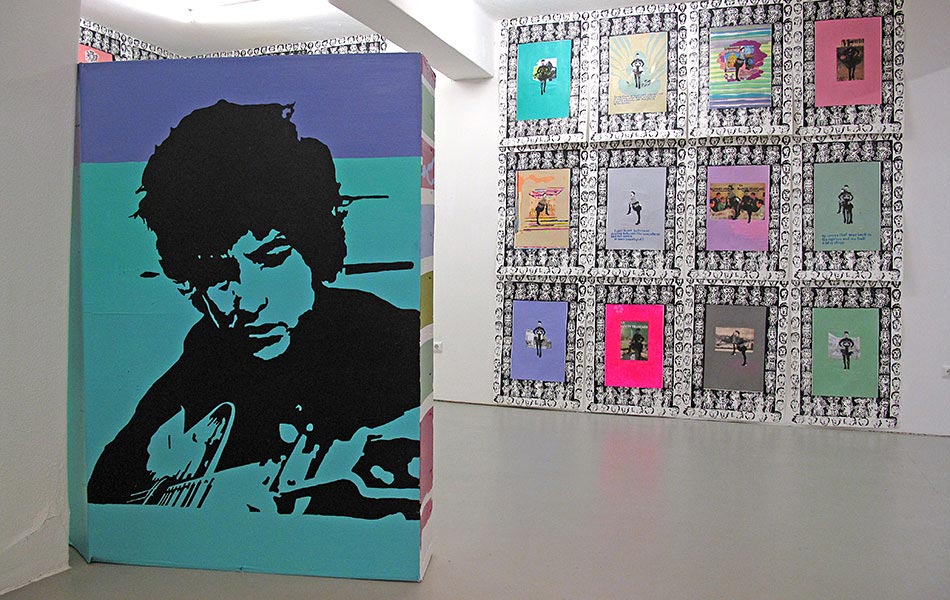

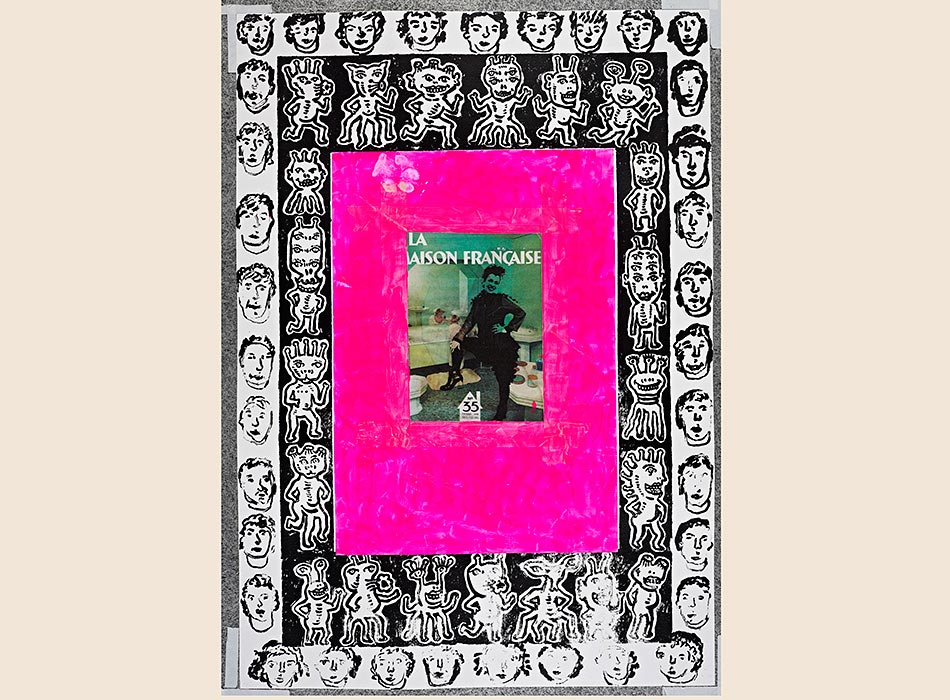

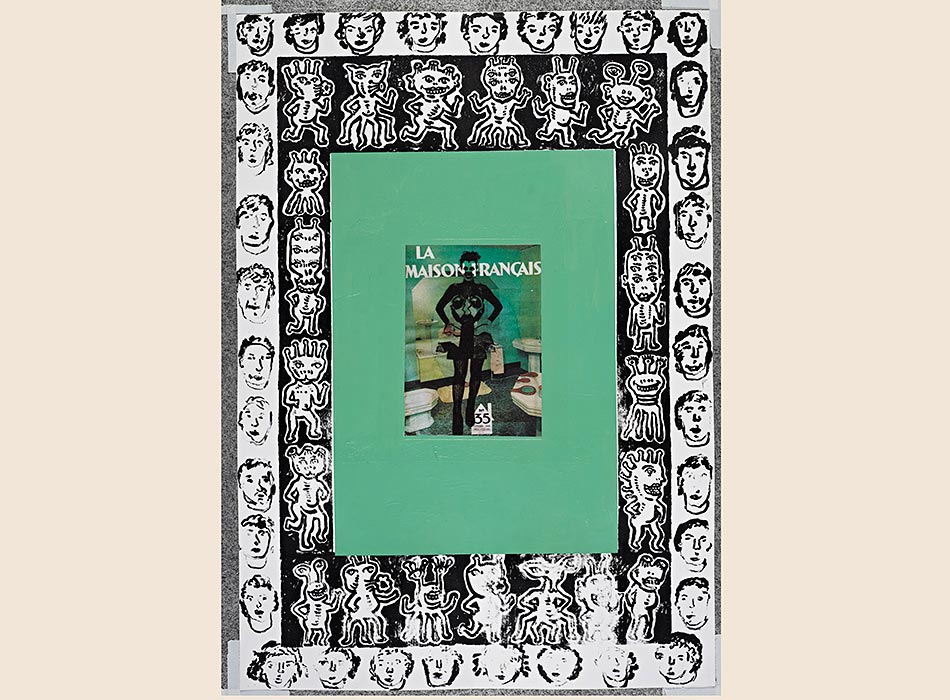

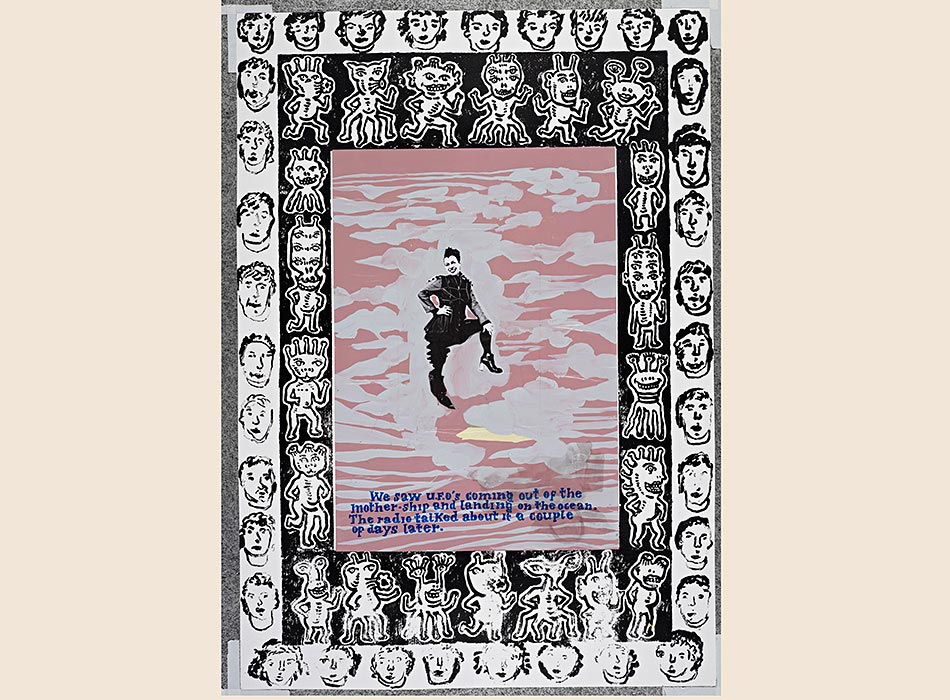

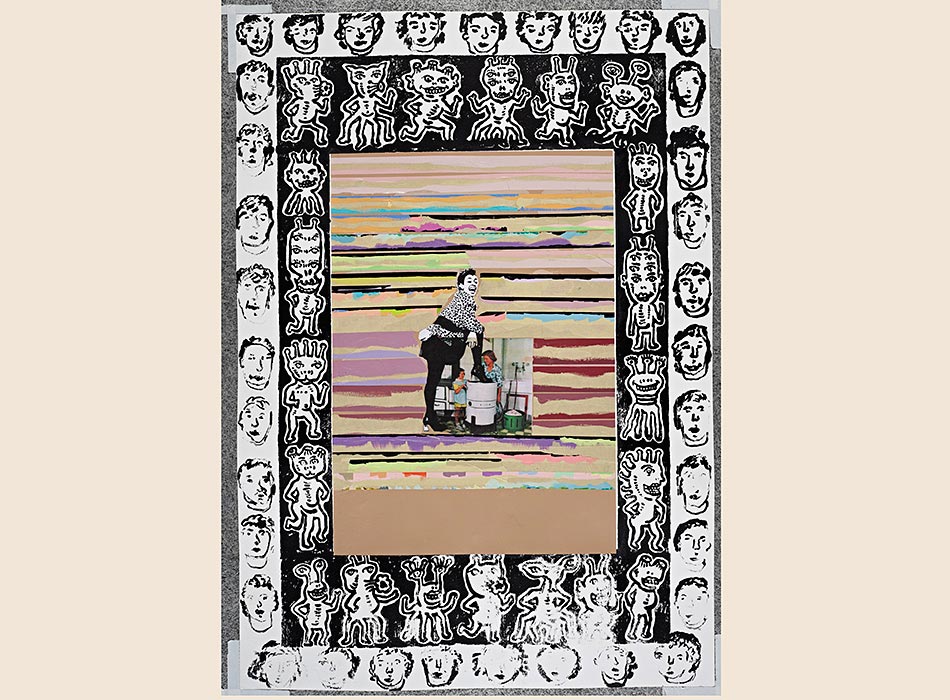

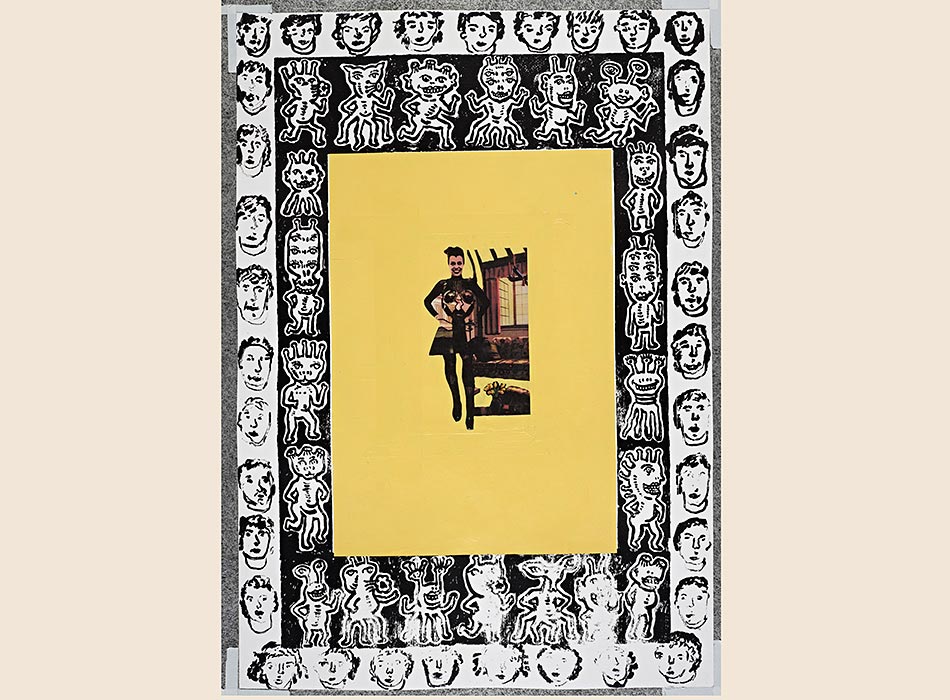

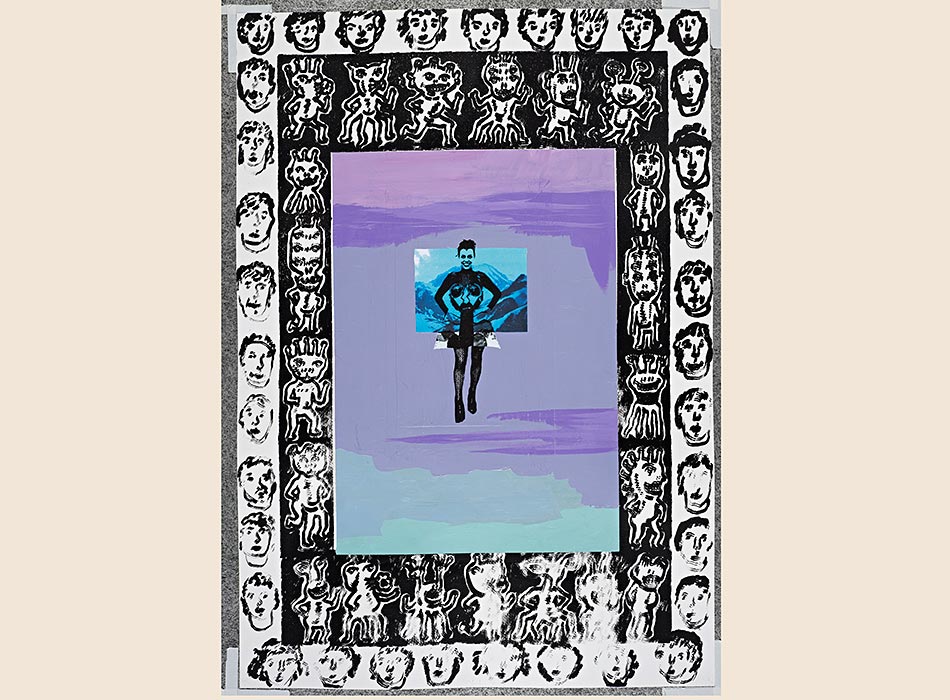

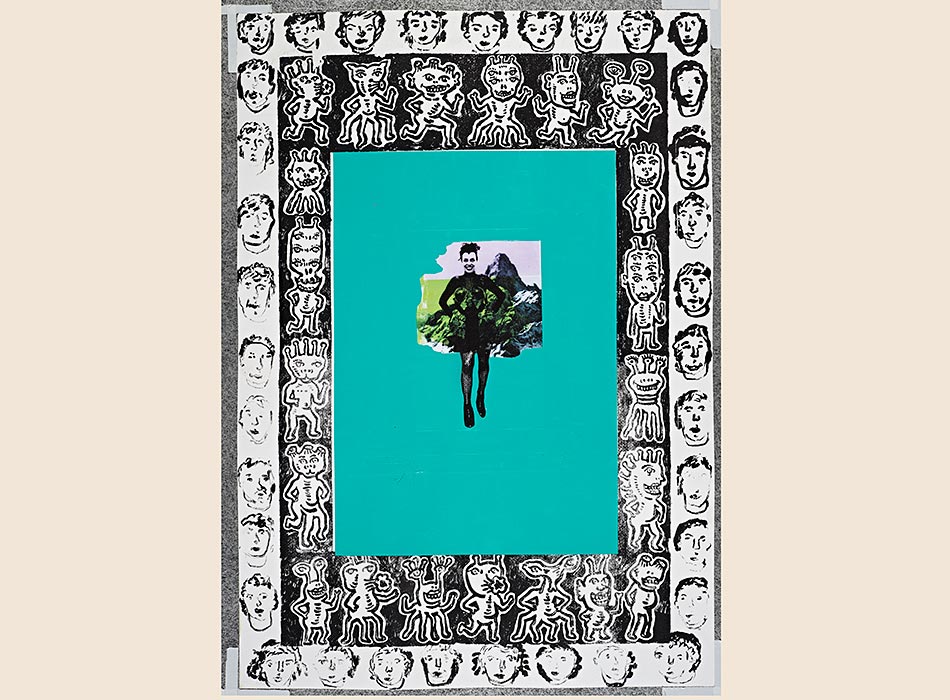

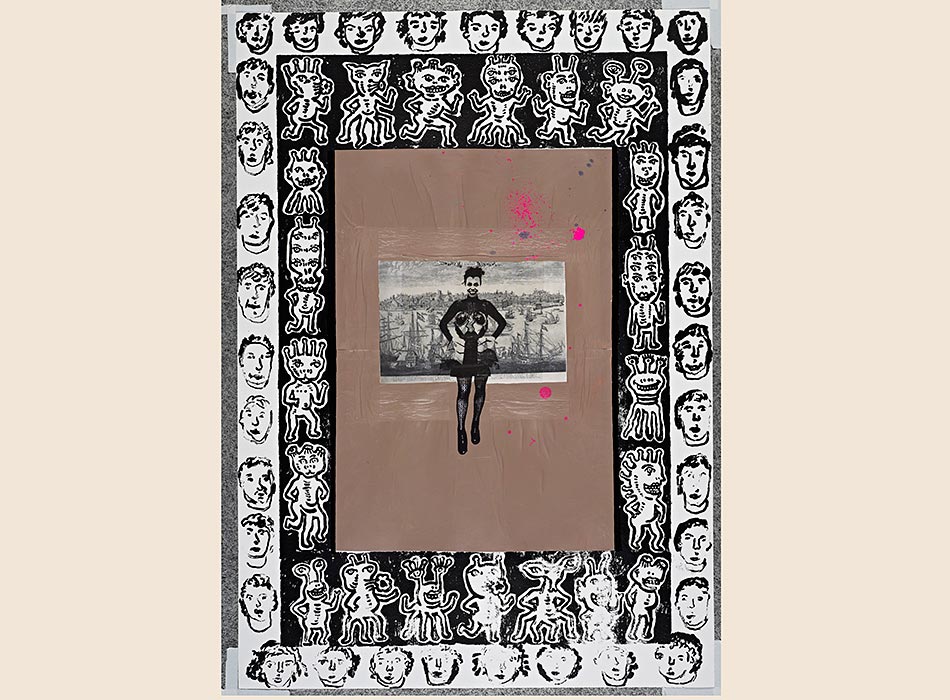

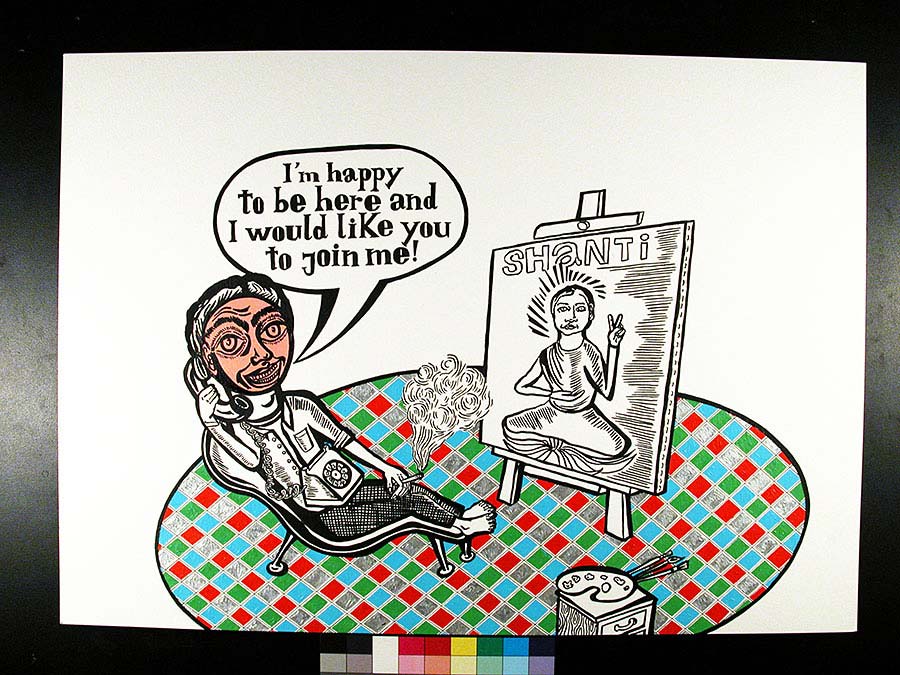

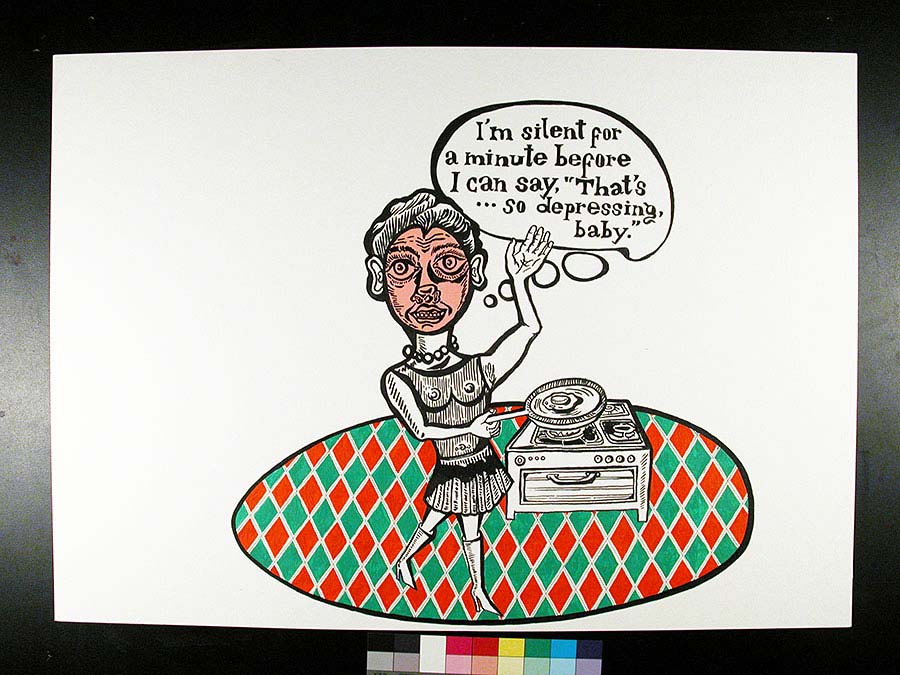

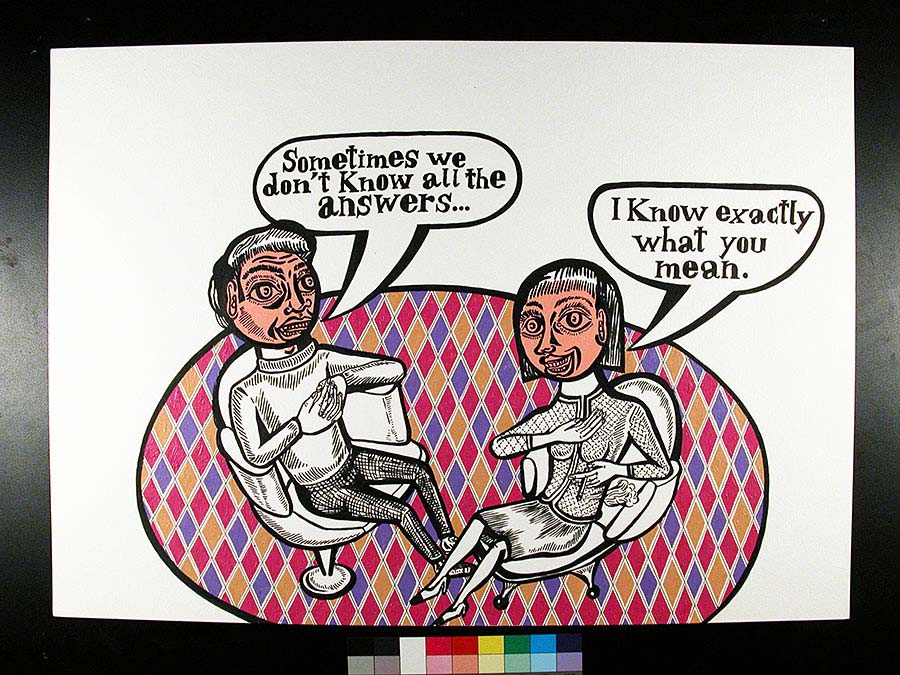

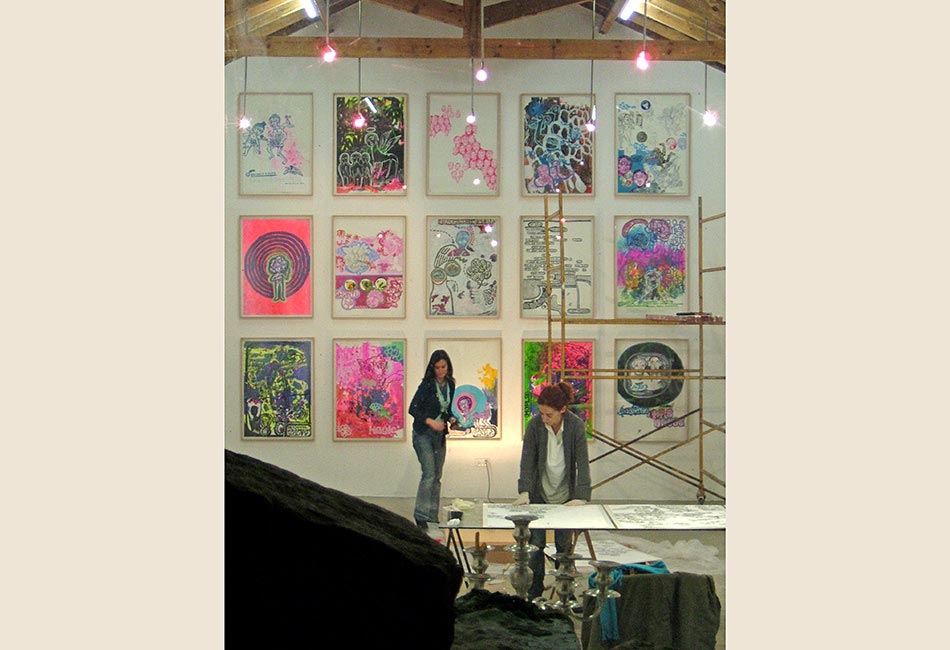

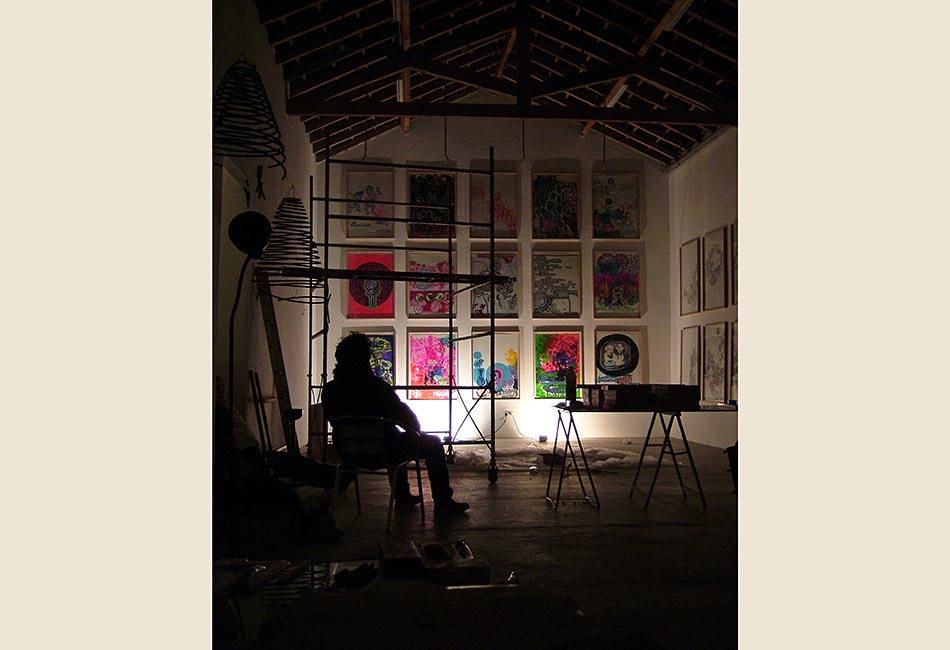

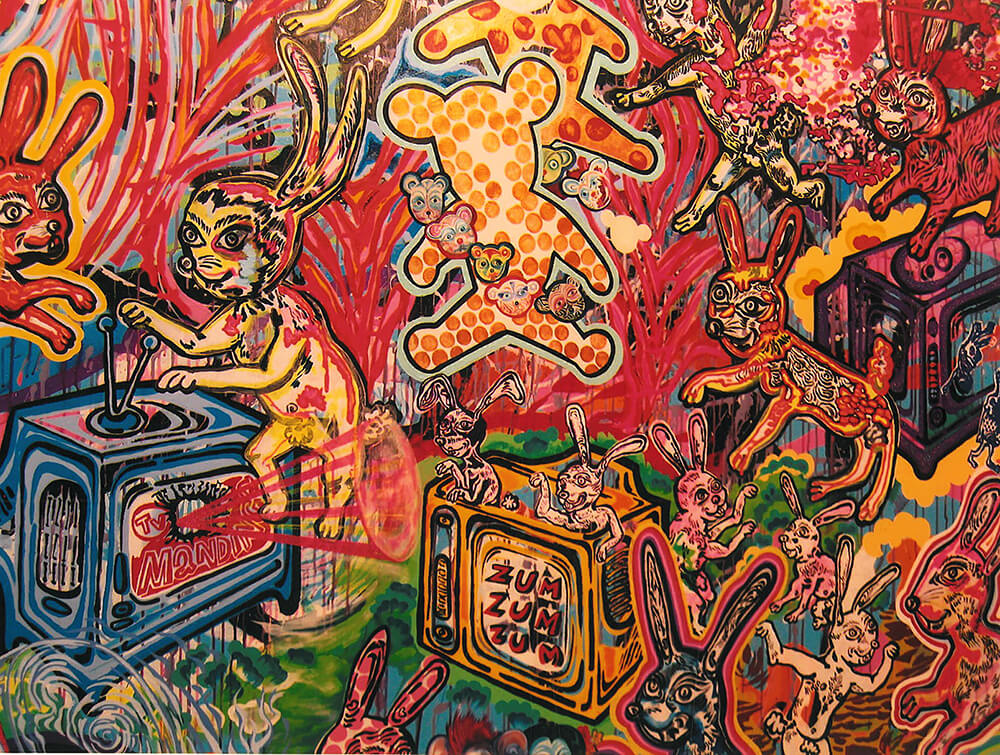

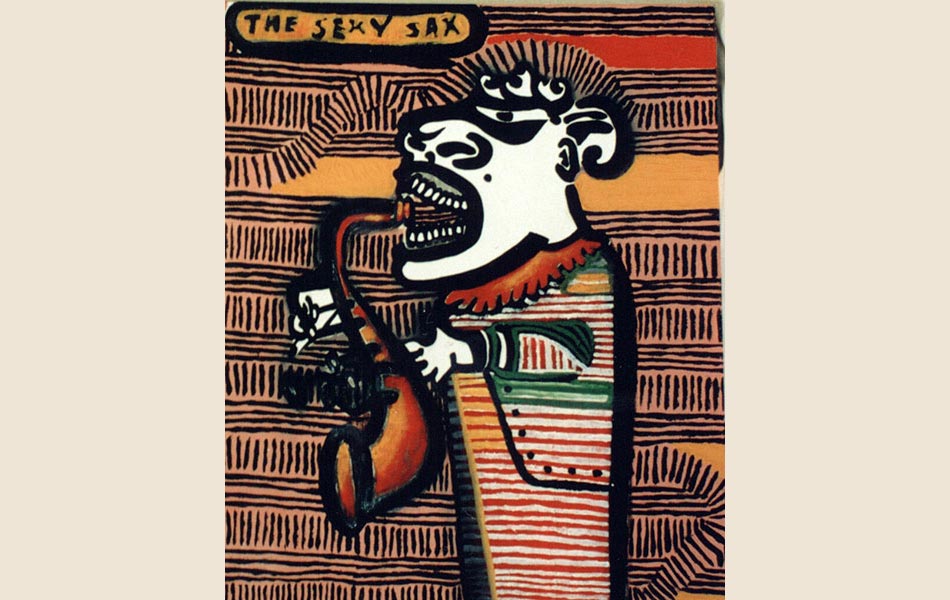

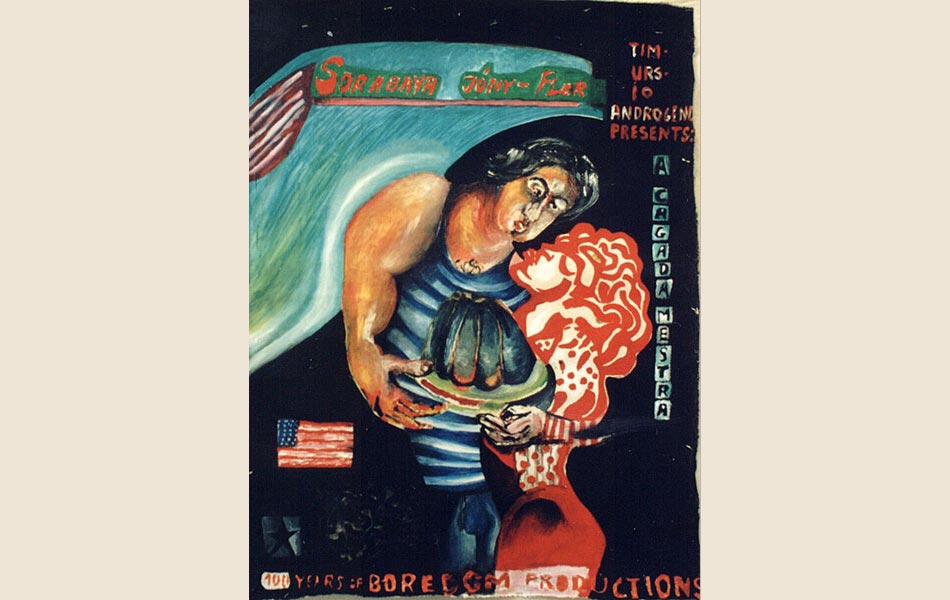

“Funky Wallpaper”, Galeria Jorge Shirley, 2010

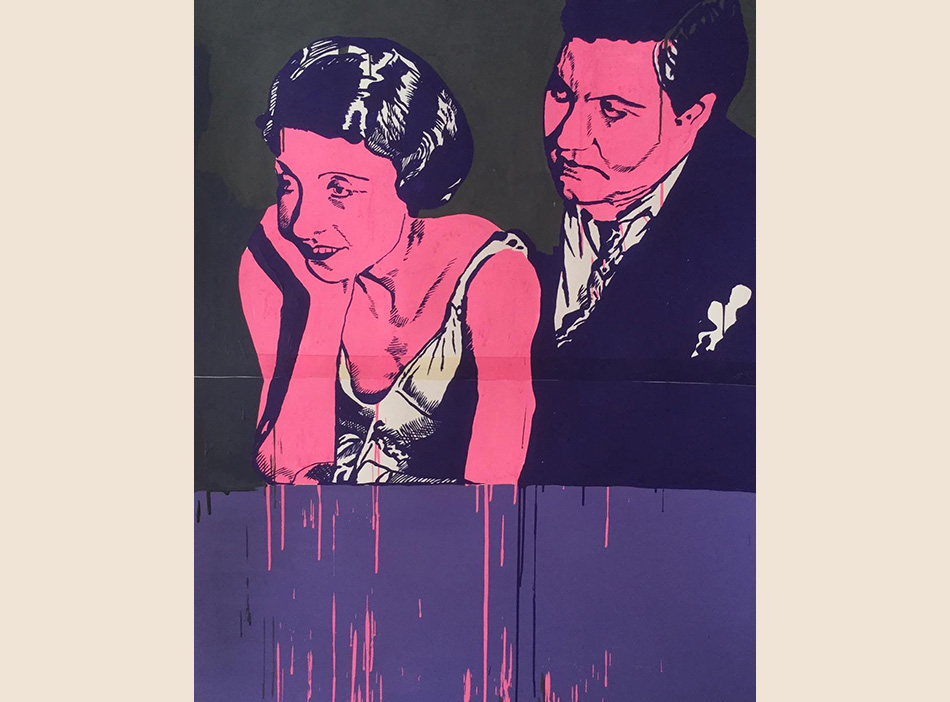

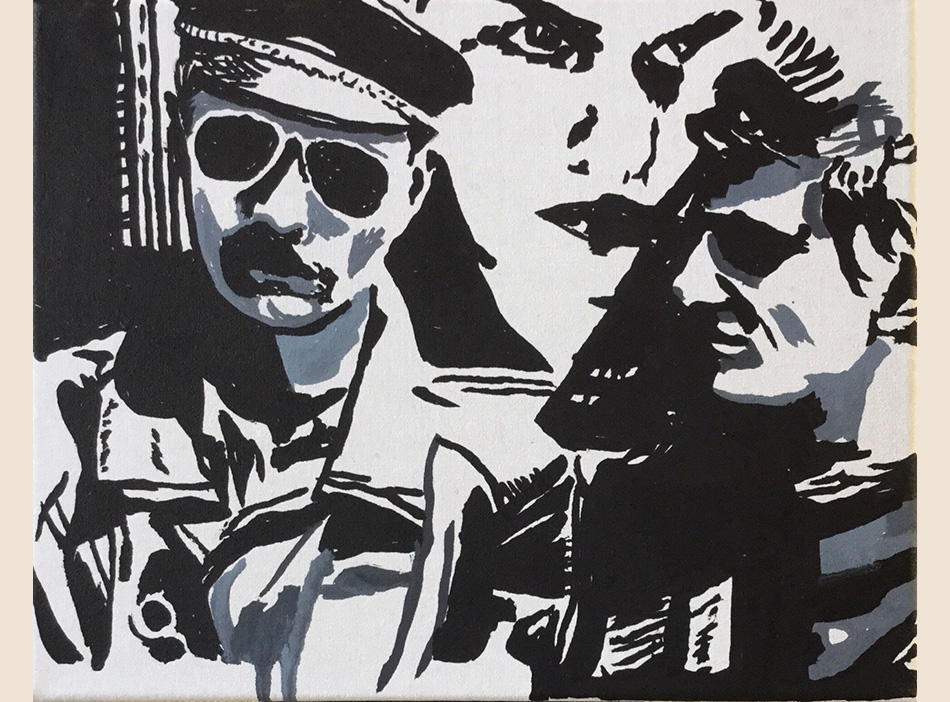

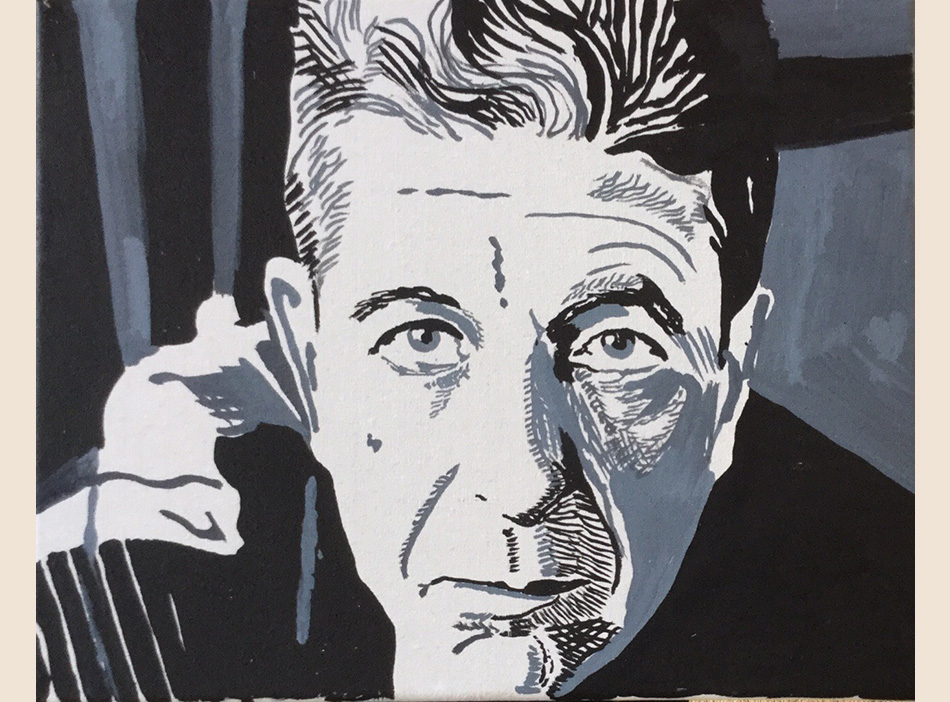

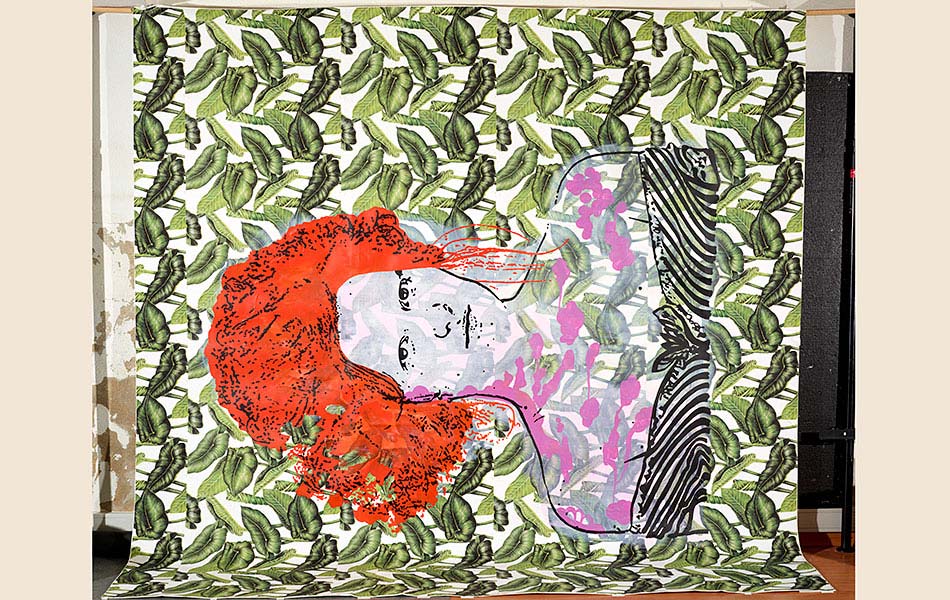

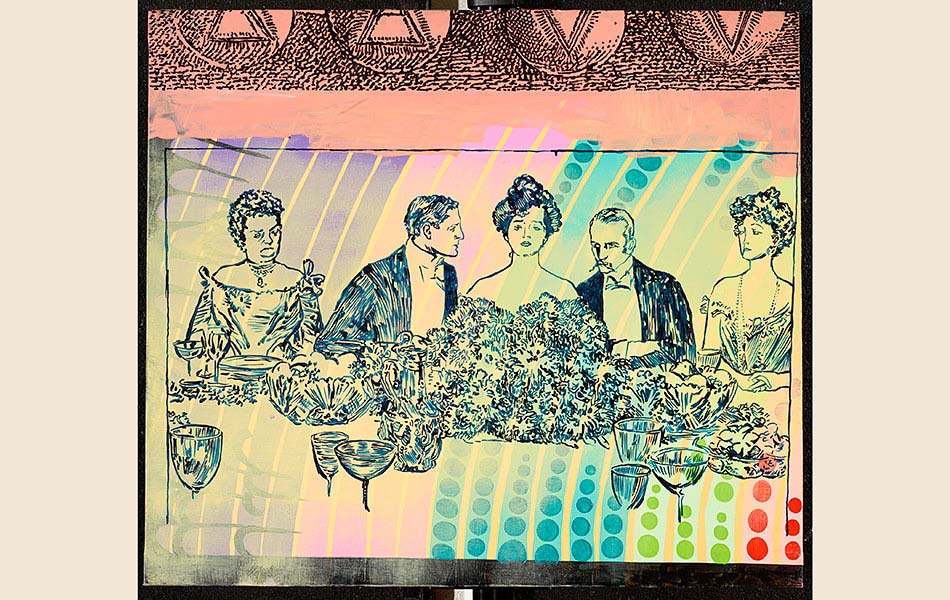

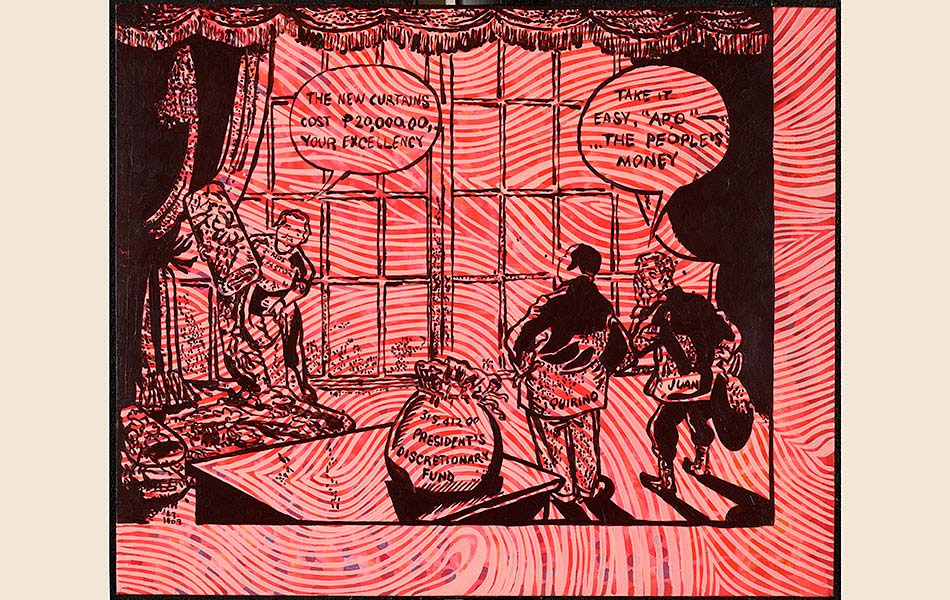

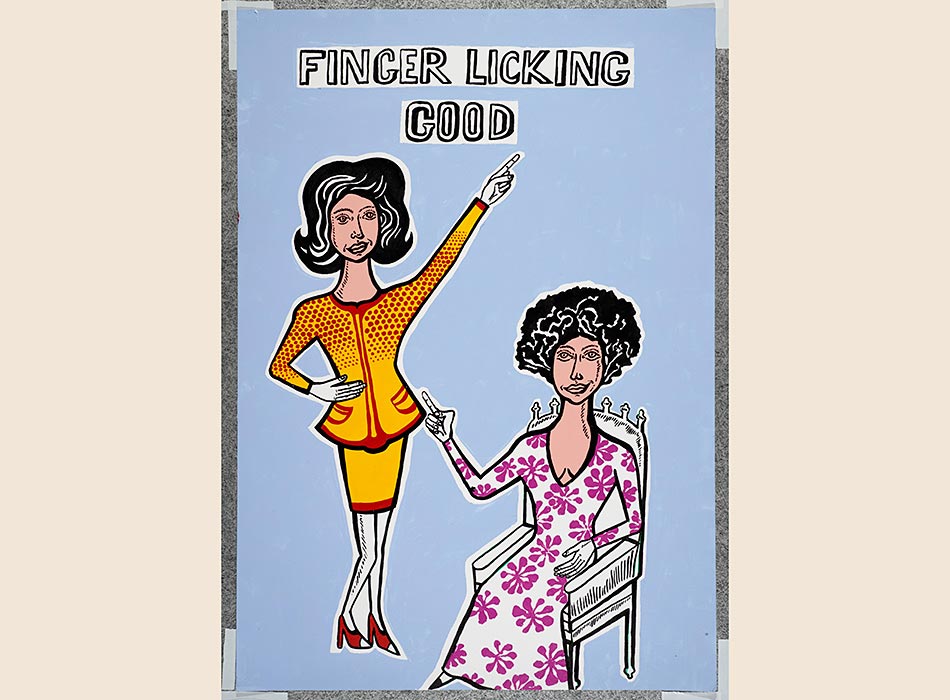

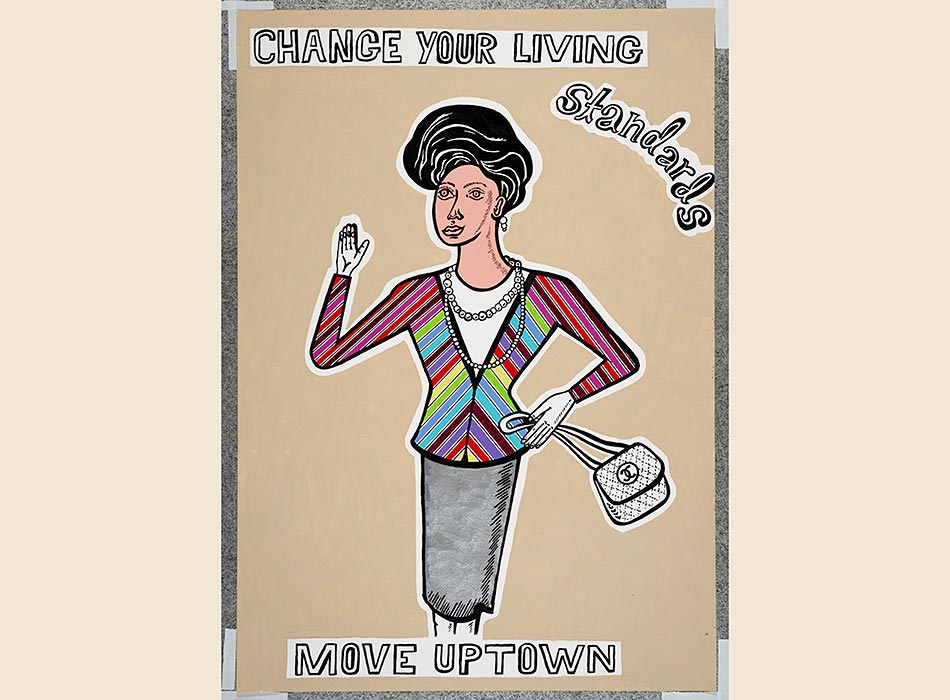

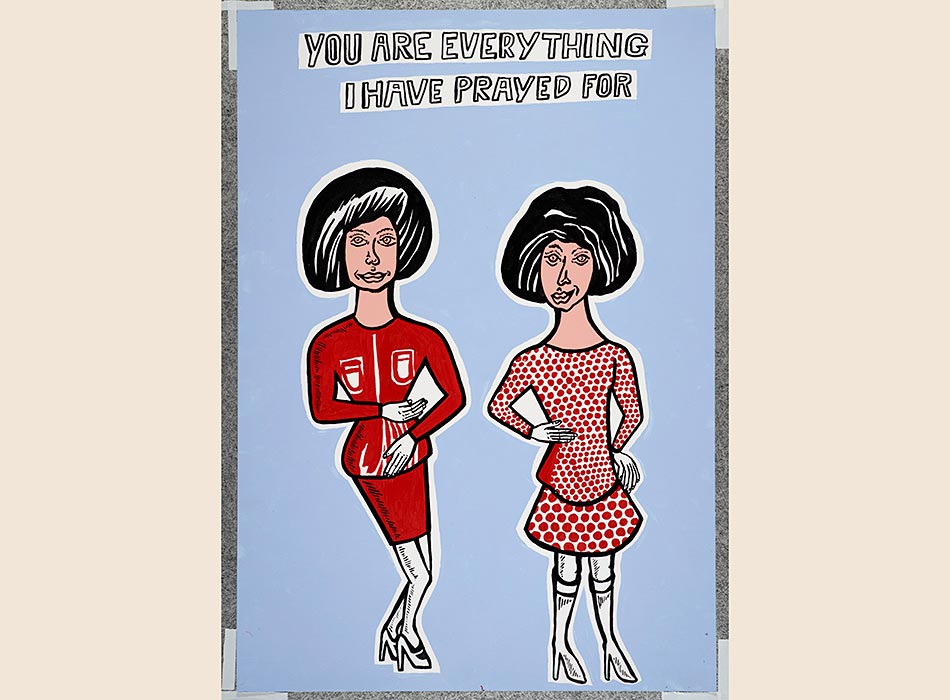

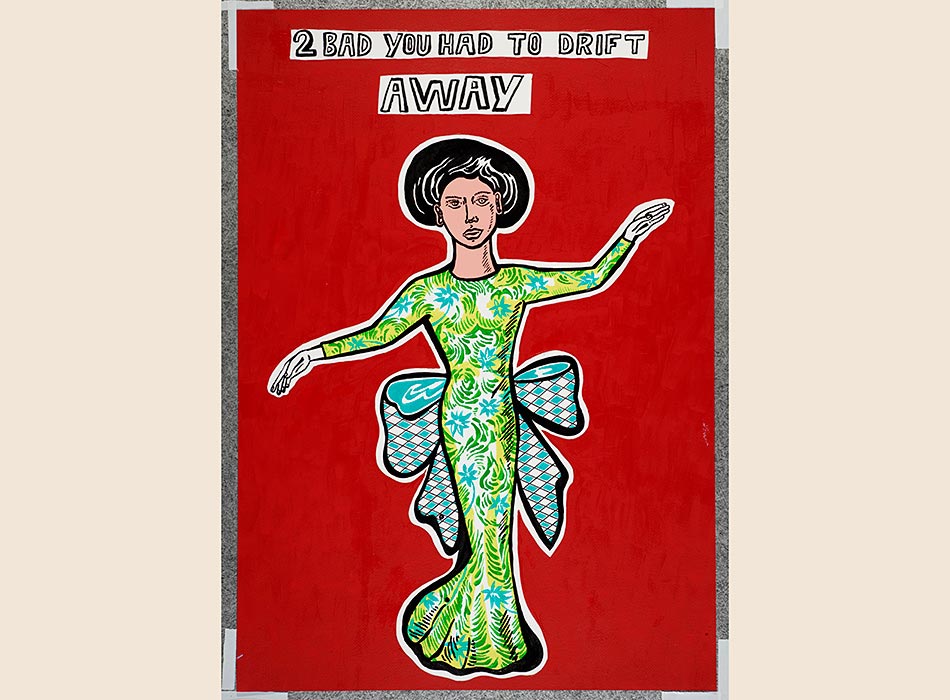

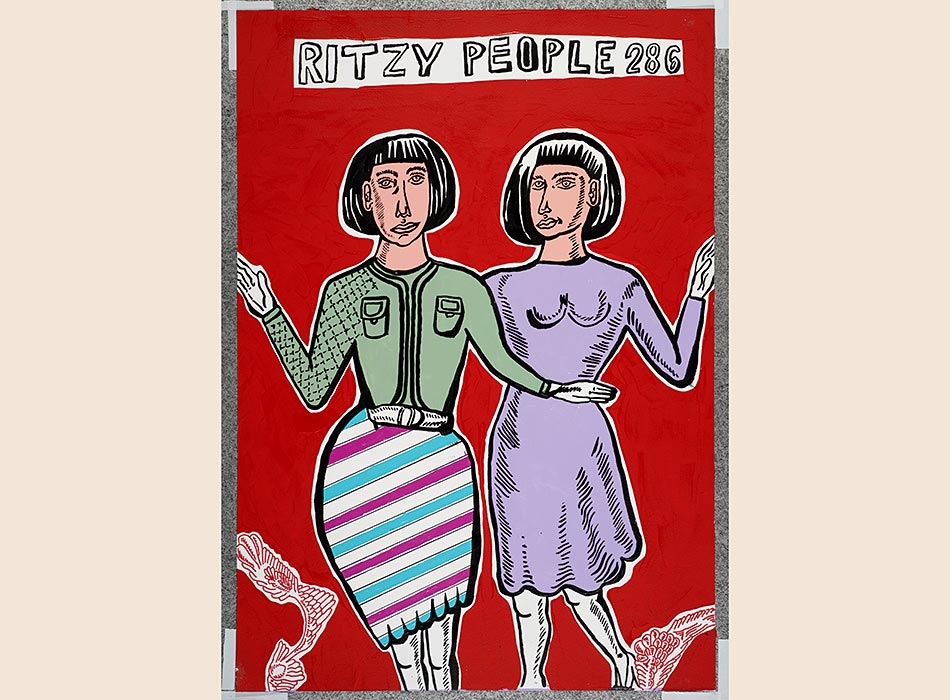

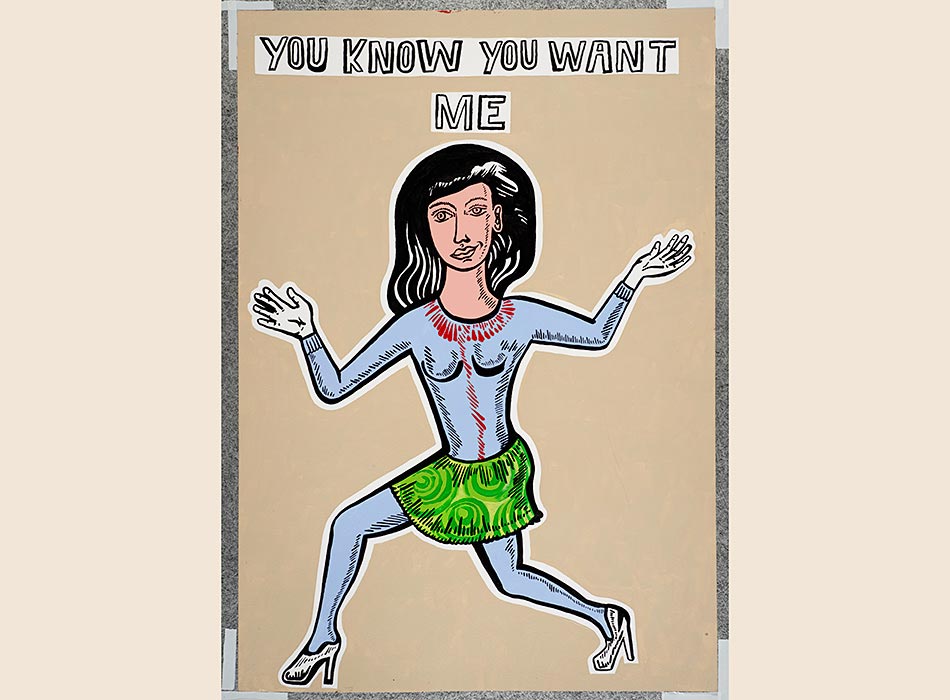

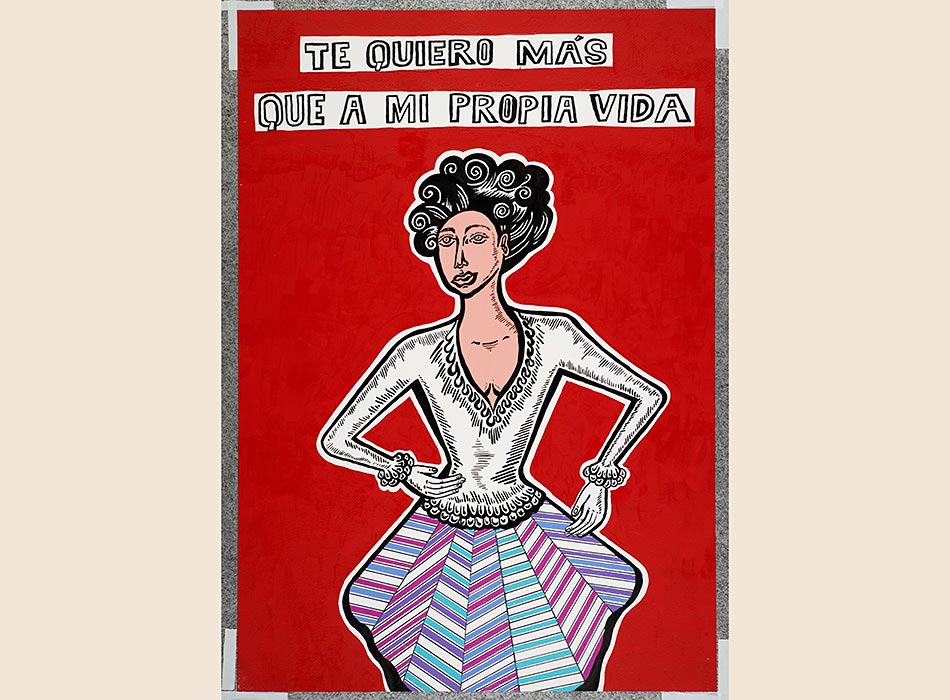

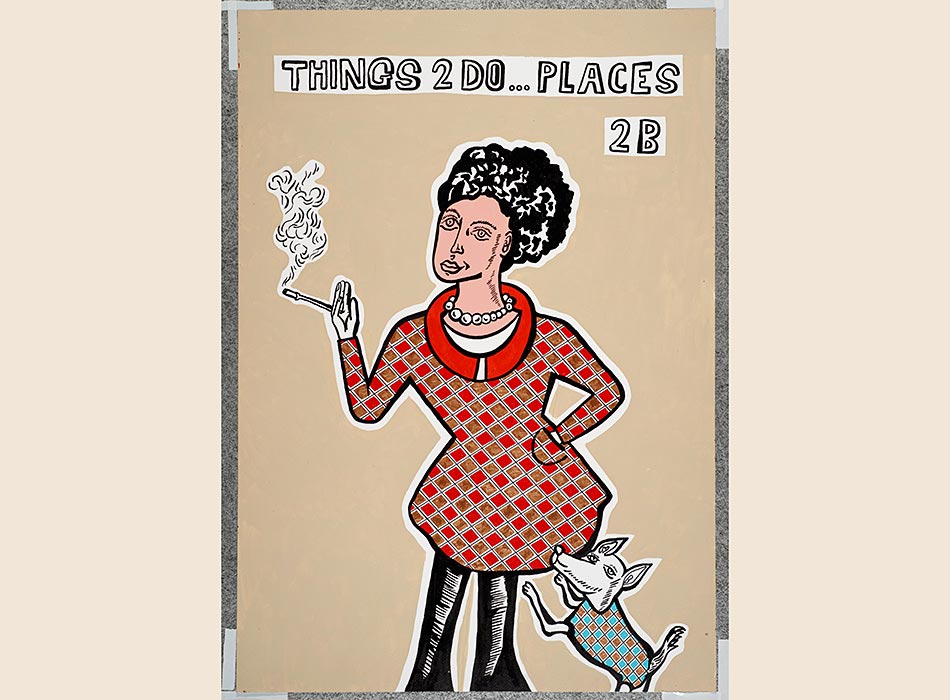

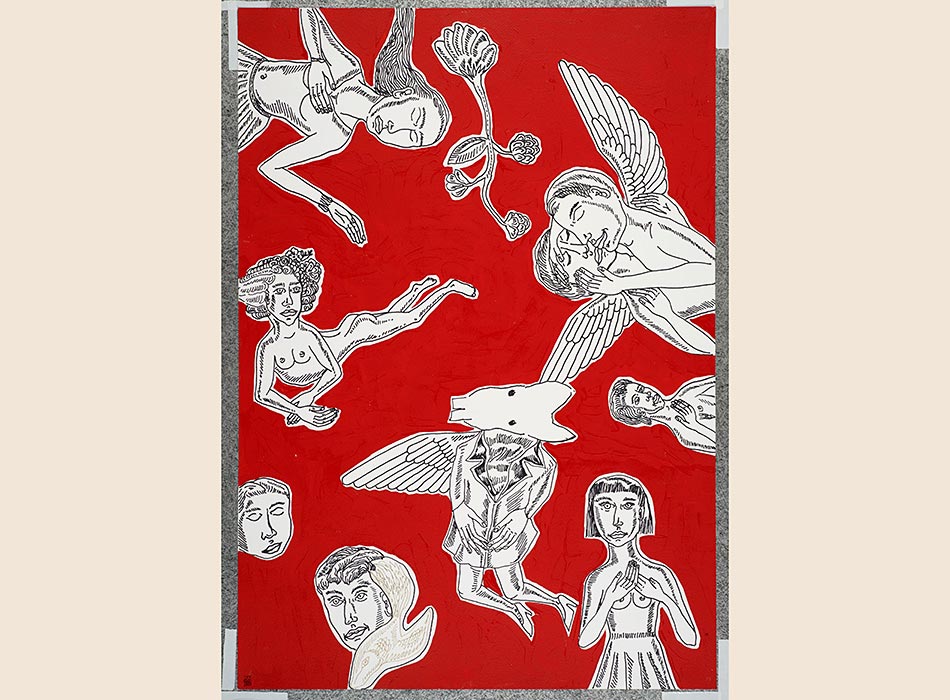

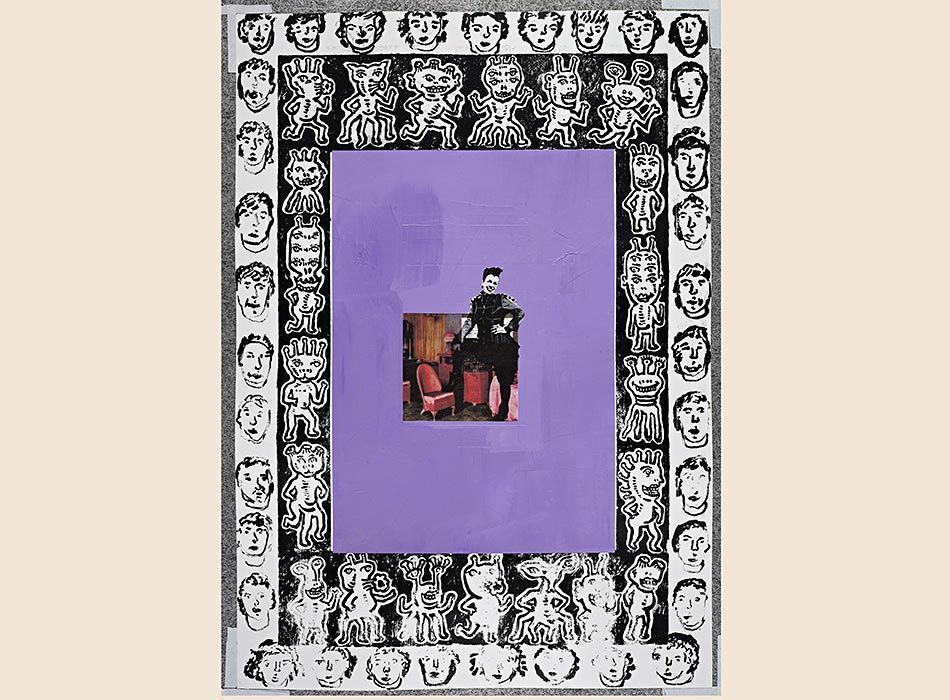

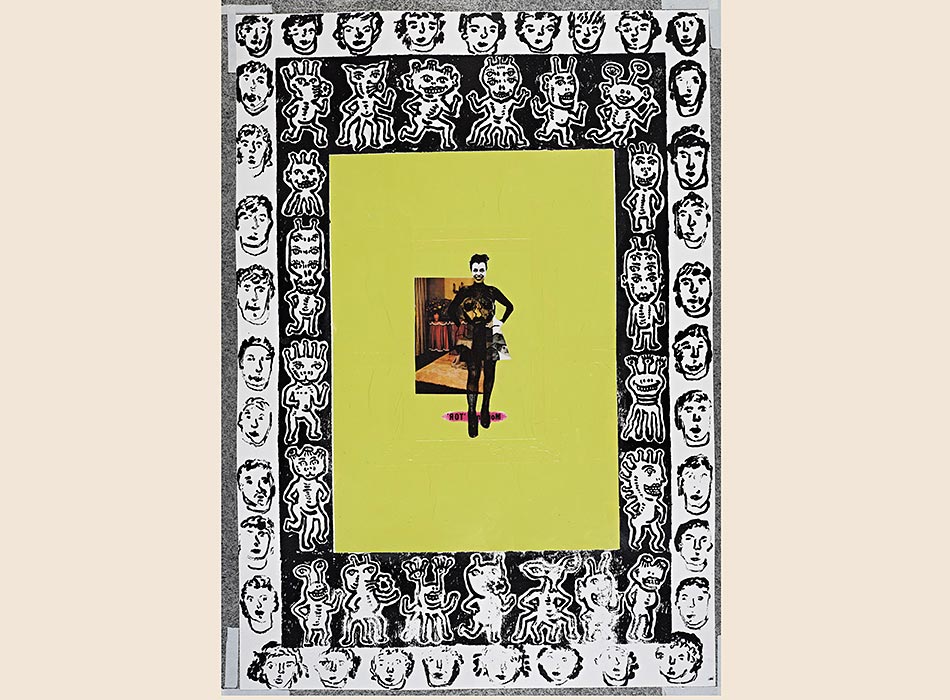

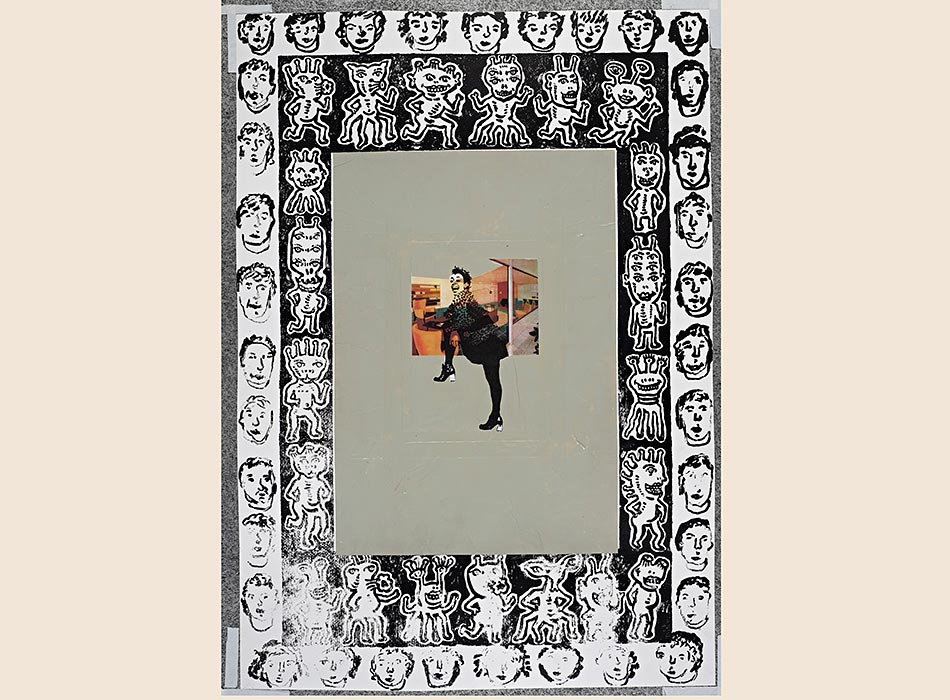

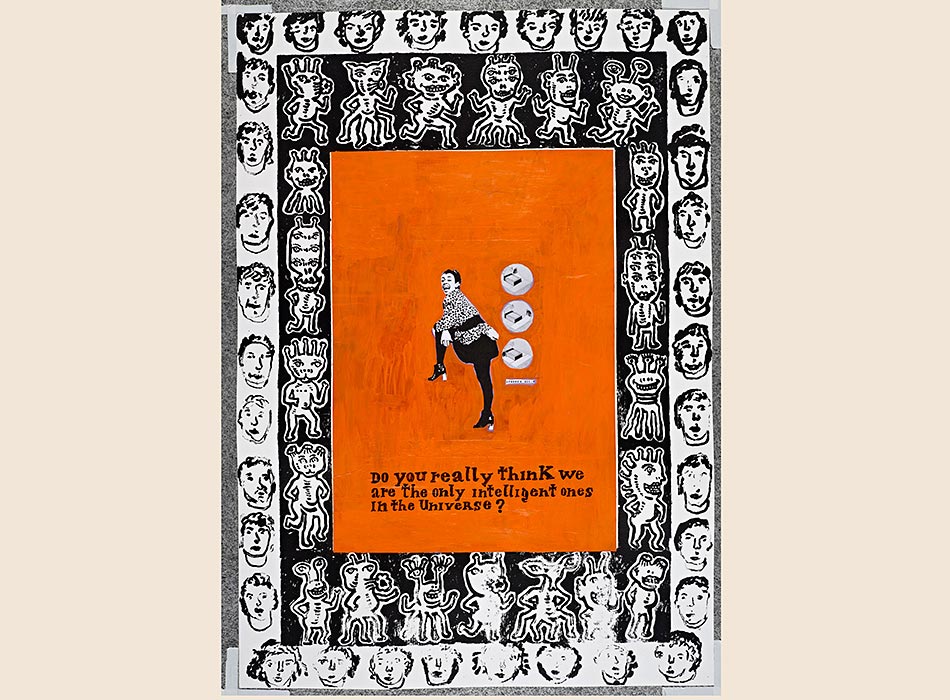

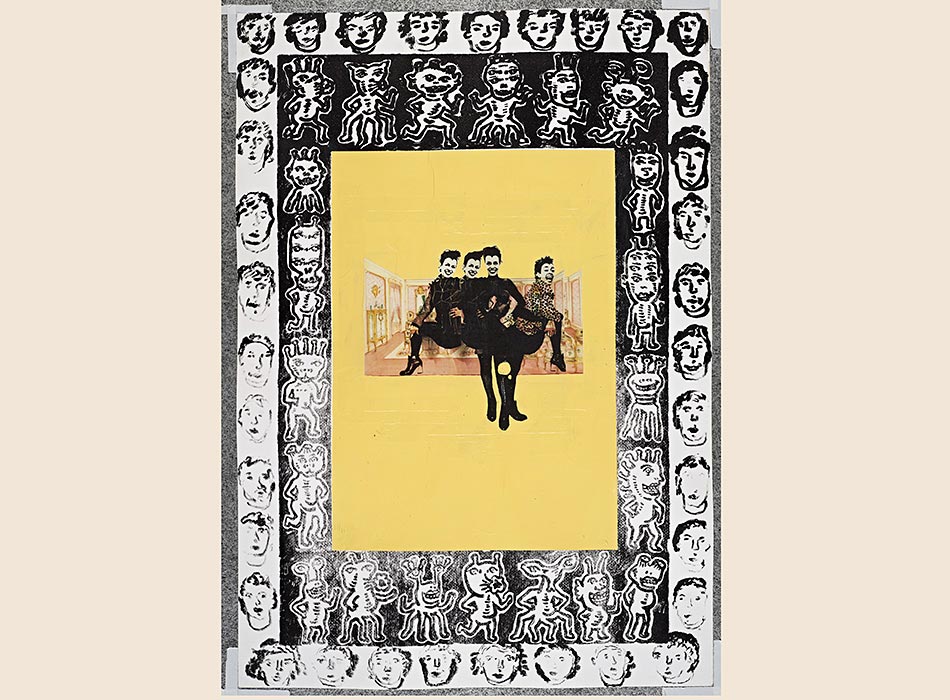

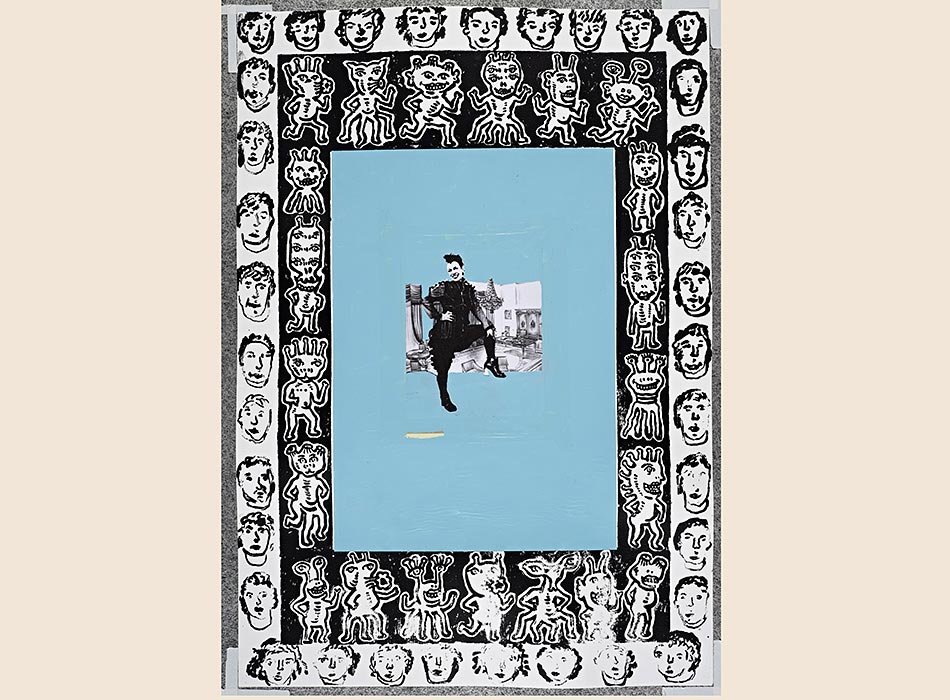

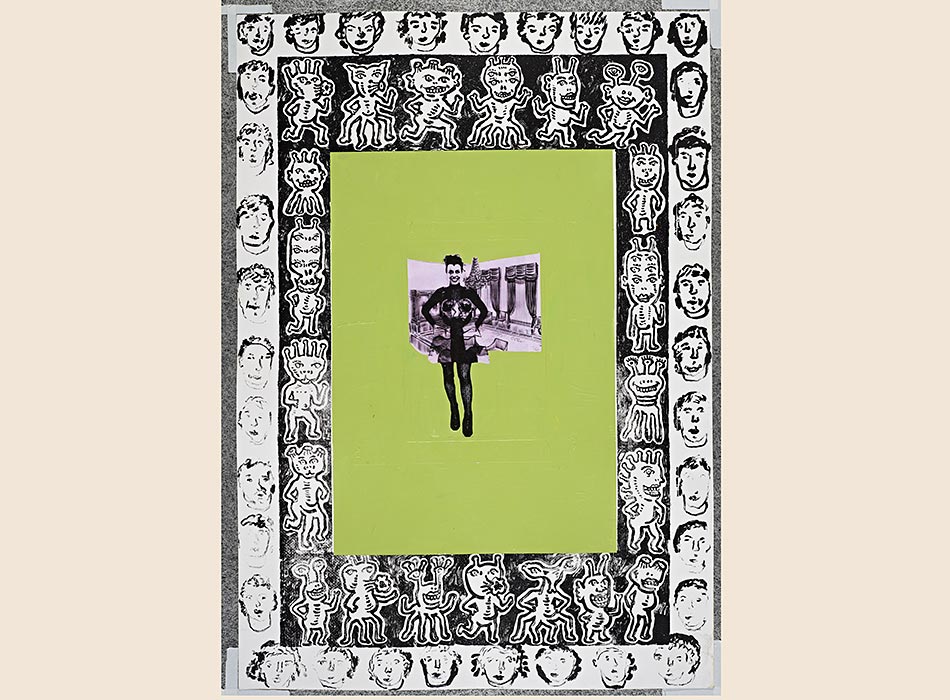

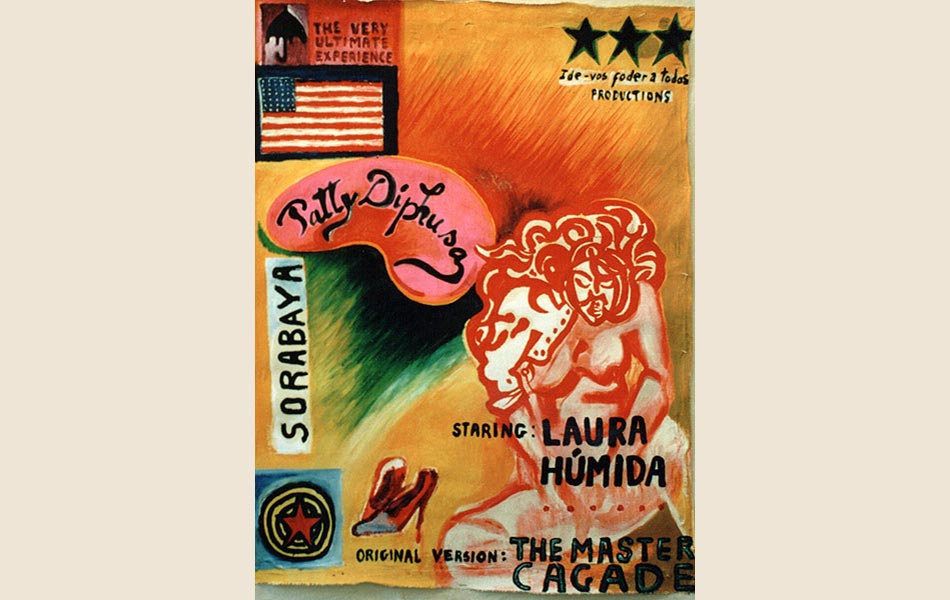

Ritzy People, 2009-2010

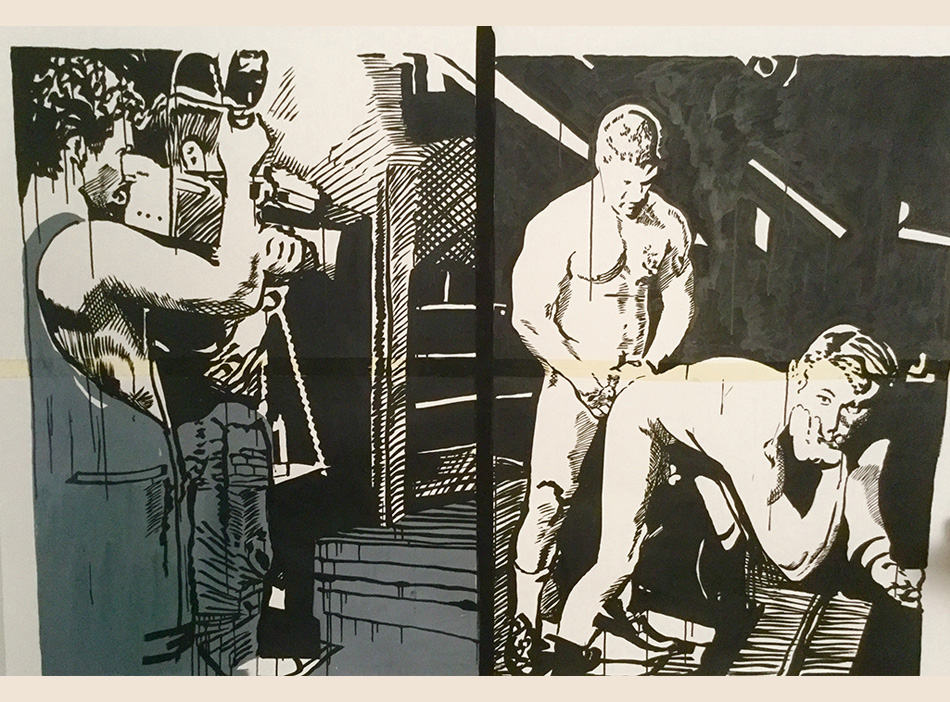

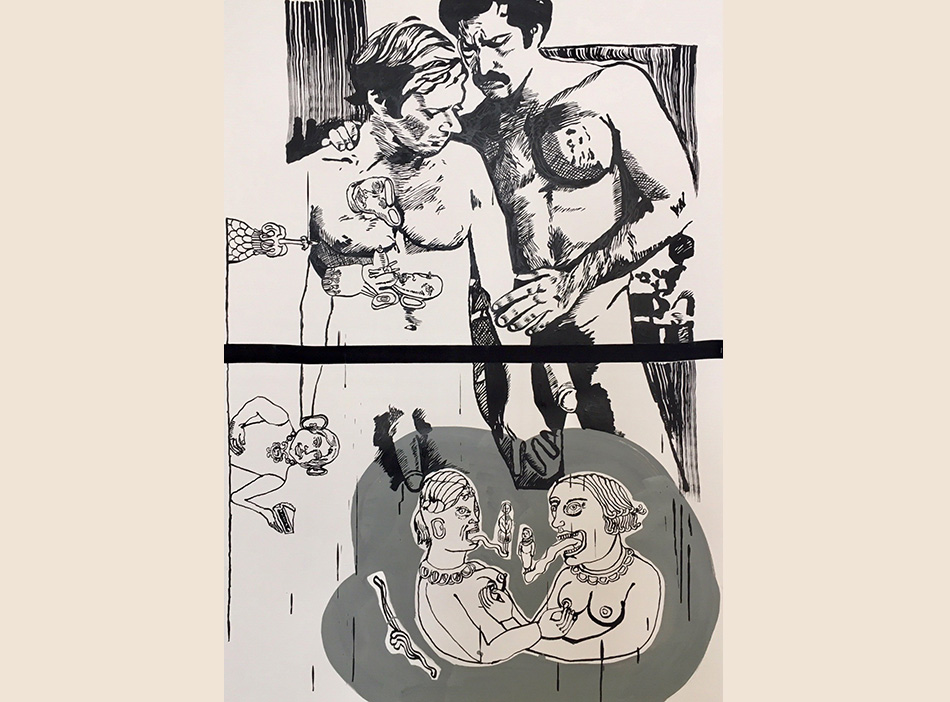

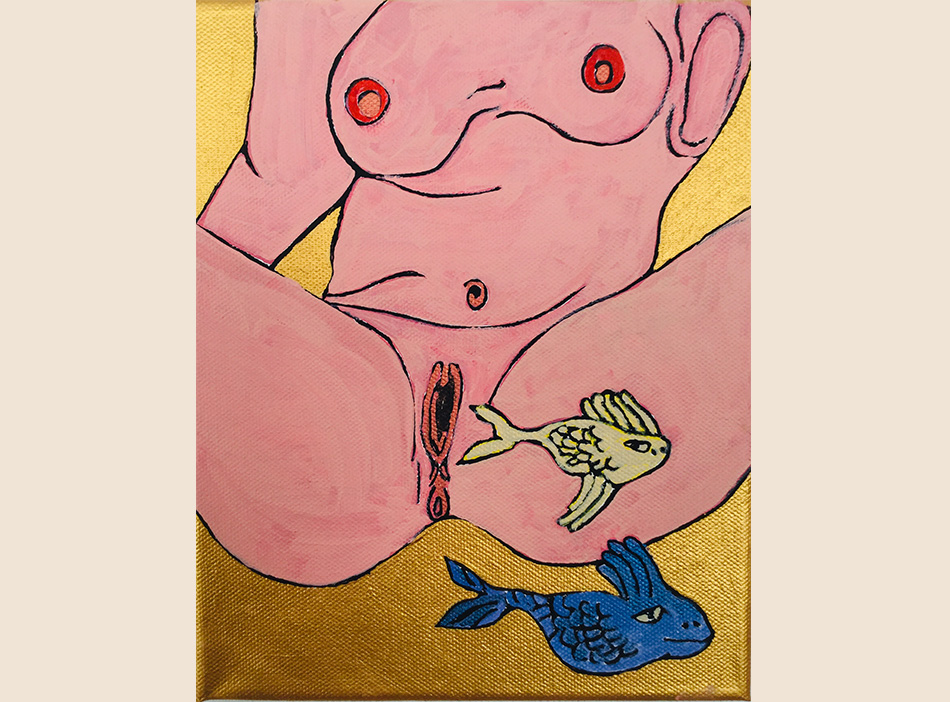

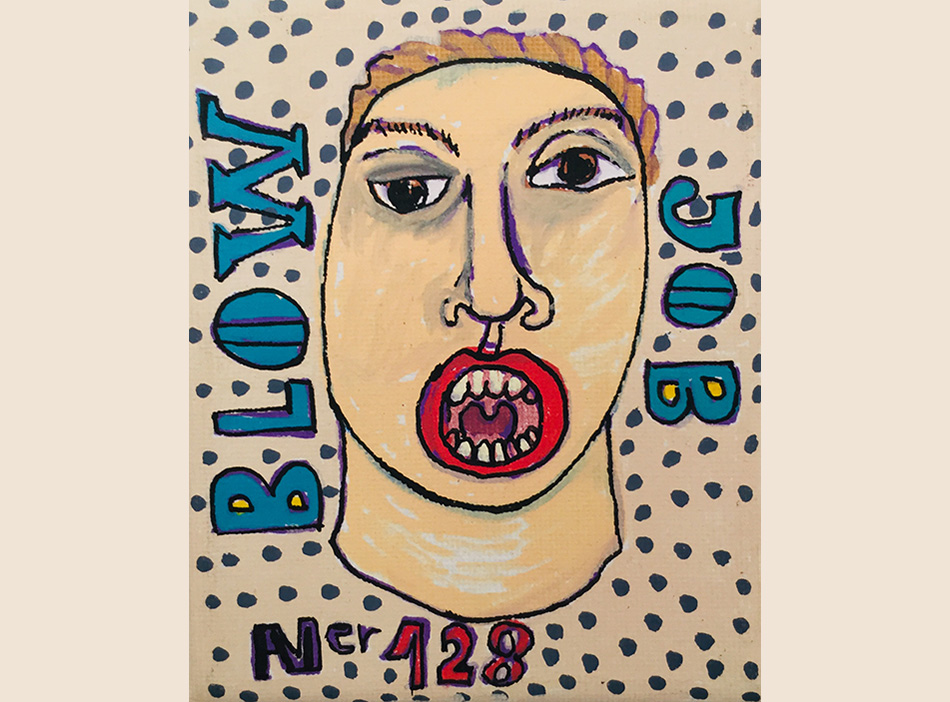

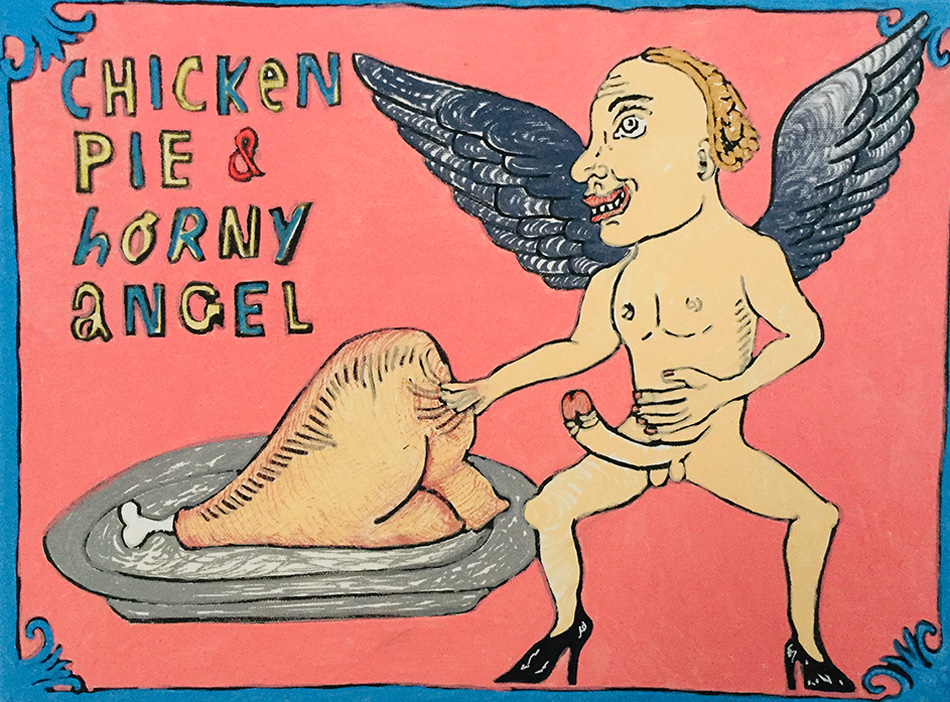

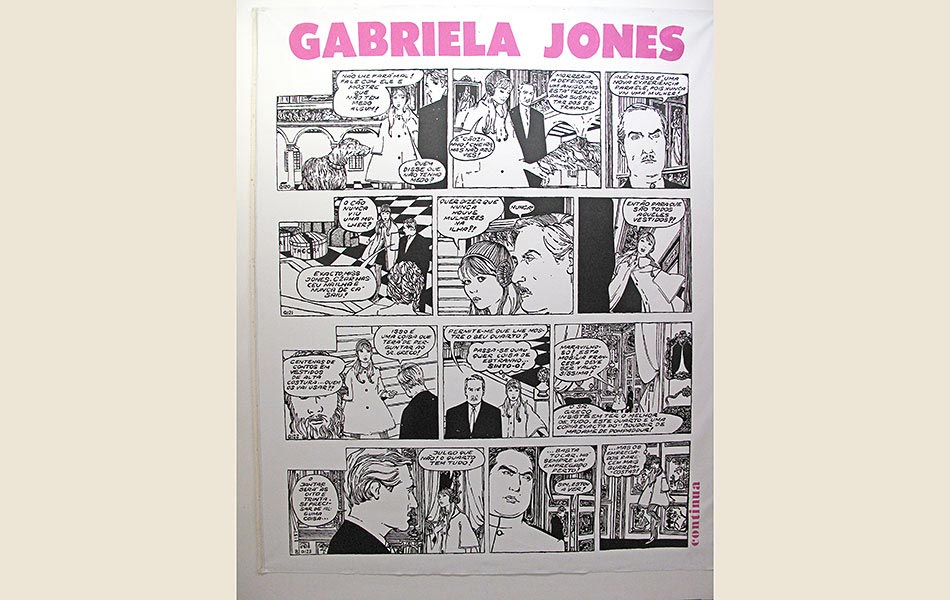

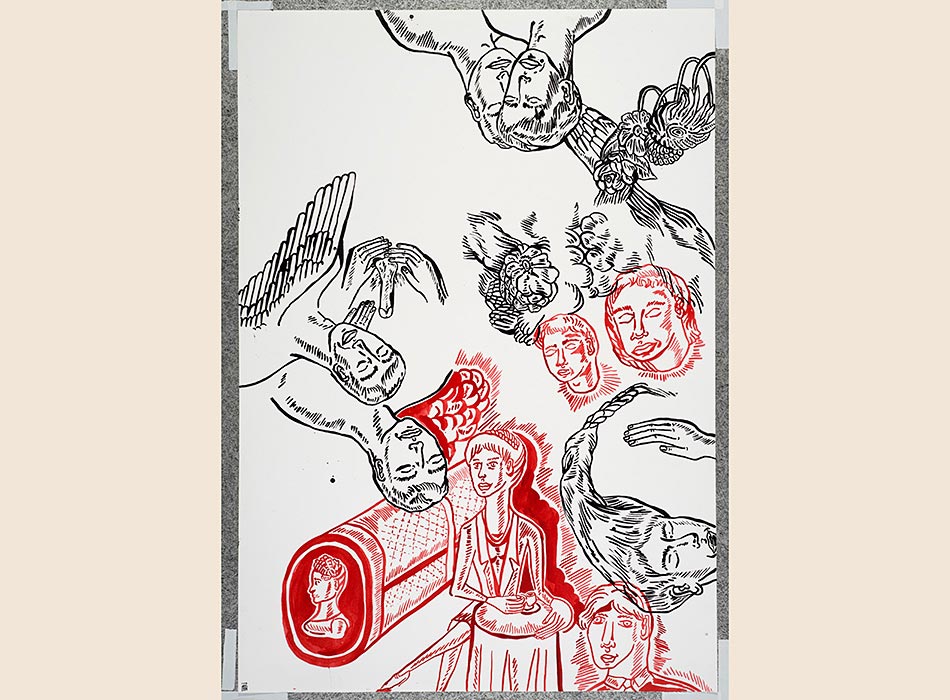

Desenhos Eróticos, 2009-2010

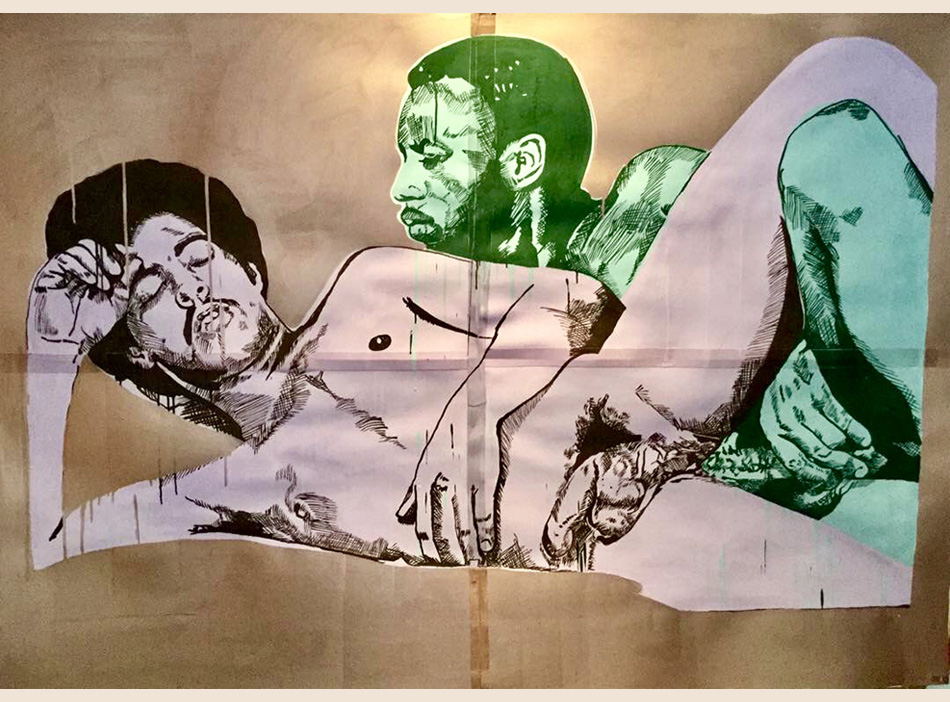

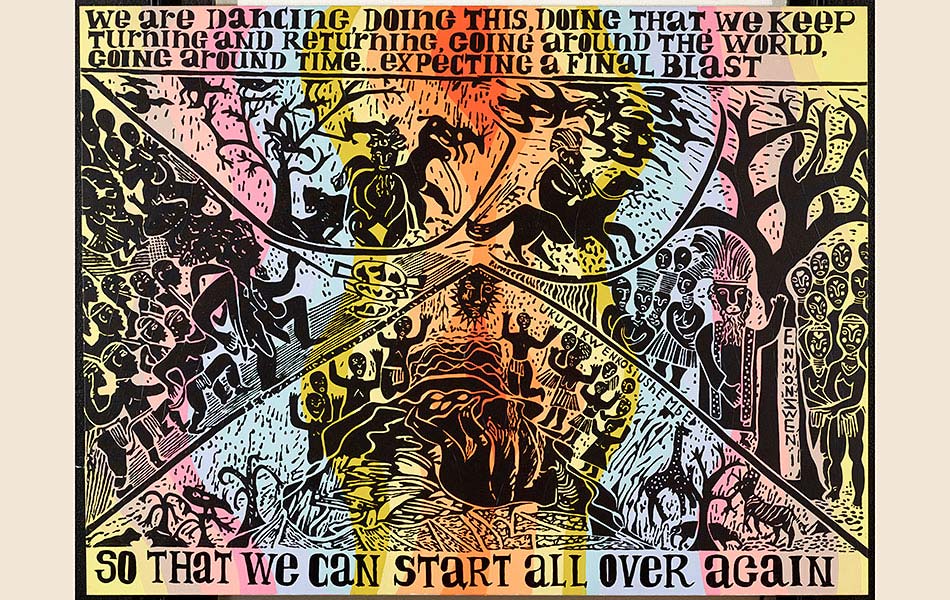

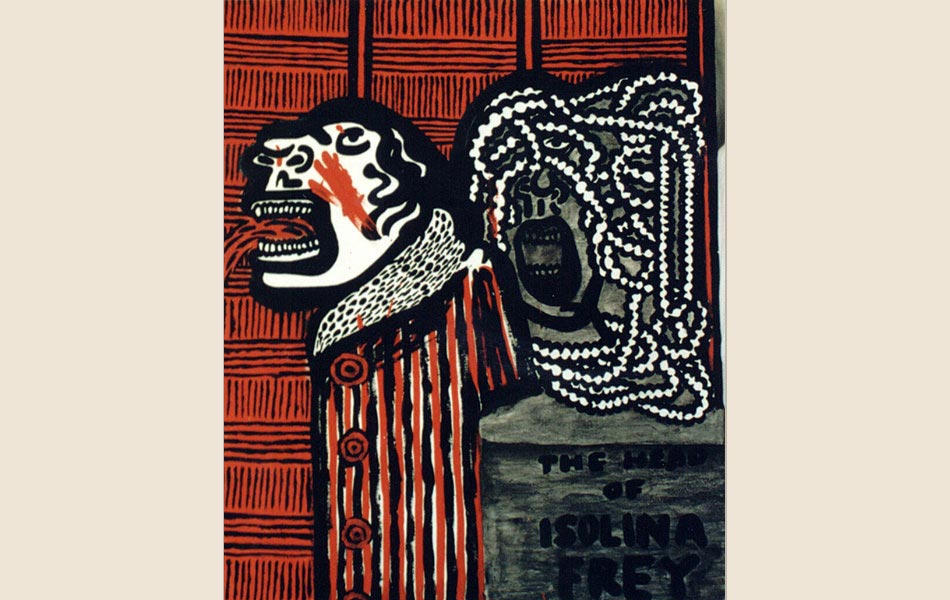

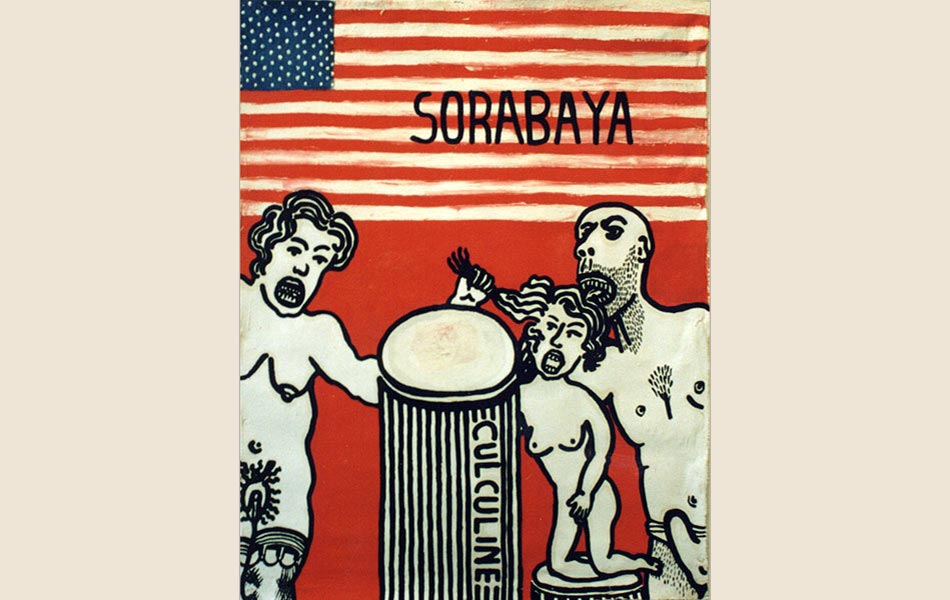

Zambeze Series, 2009-2010

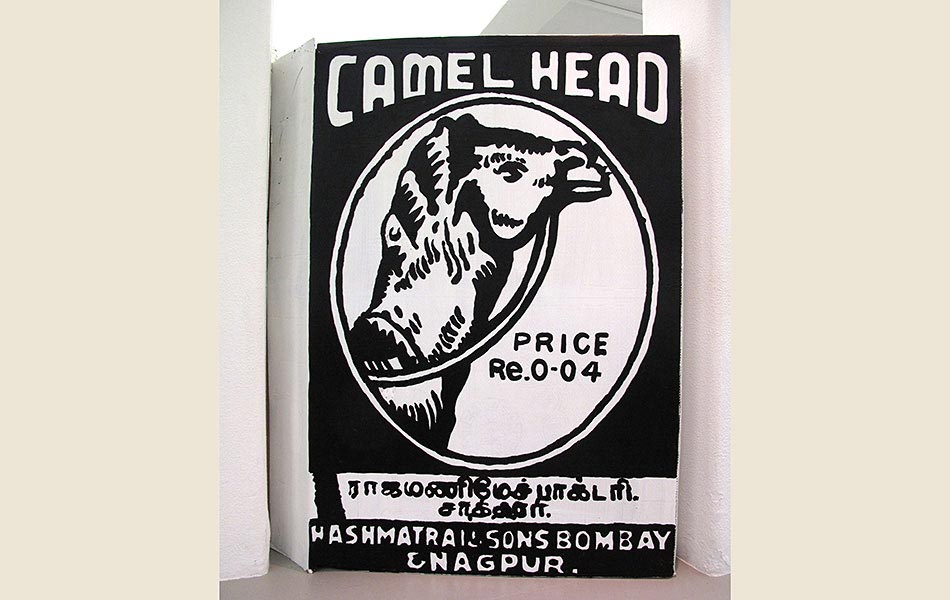

Gifts from where I’ve been, 2009

About the book

This book gathers a selection of the works made over the last four years and which are a reflection of the places and of the people that I have run into during this cycle of paintings, travels and life experiences.

What truly fascinates me about painting is the manner how it adjusts, shapes and merges itself with my own life. And in such sense, I cannot imagine being anything else but a painter.

Painting is a recurrent vehicle through which a reconnection is established with the world in which I live and act, a way to broaden out my awareness of myself, of the others, of the tenuous frontier that separates us and of the synchronism that leads us to encounter one another at the right time.

Invariably, I prefer painting to speaking about my work. I would rather have my painting speak for itself and ideally, for an interesting dialogue to arise with the viewer.

There has always been a somewhat ineffable and mysterious nature in this process of collecting vibrations, smells, sounds, images, memories, visions, colours, words and sensations that incessantly mingle together, materializing themselves into drawings and paintings through which I weave pieces of stories that only make sense when they are shared.

Thus, I would just like to deeply thank everybody that has contributed to this pursuit of mine and that has made it possible to tell these stories, as well as to everybody who will be willing to listen to them.

Wandering Chronicles by Celso Martins

In the Odyssey, Homer tells it took Ulysses ten years to reach Ithaca after the end of the Trojan war. And the adventures and misadventures were so many that the West never ceased to resort to them to look at itself in the mirror, turning the very idea of travelling into a mythological reference.

From Camões to Lord Byron, from Rimbaud to Gauguin, Visual Arts and Literature would have been very different over the last centuries without this sort of compulsion that can take on the most varied features (escape, discovery, confirmation of the self), but that in any case seems to exemplarily embody the myth of transformation and individual metamorphosis.

In this era of high speed and communication anxiety, the literal travel that crosses over concrete distances and recovers an apparently lost time thickness means not only a rehabilitated encounter with the other, but a recovery of such possibility of life transfigured. Another space, another duration.

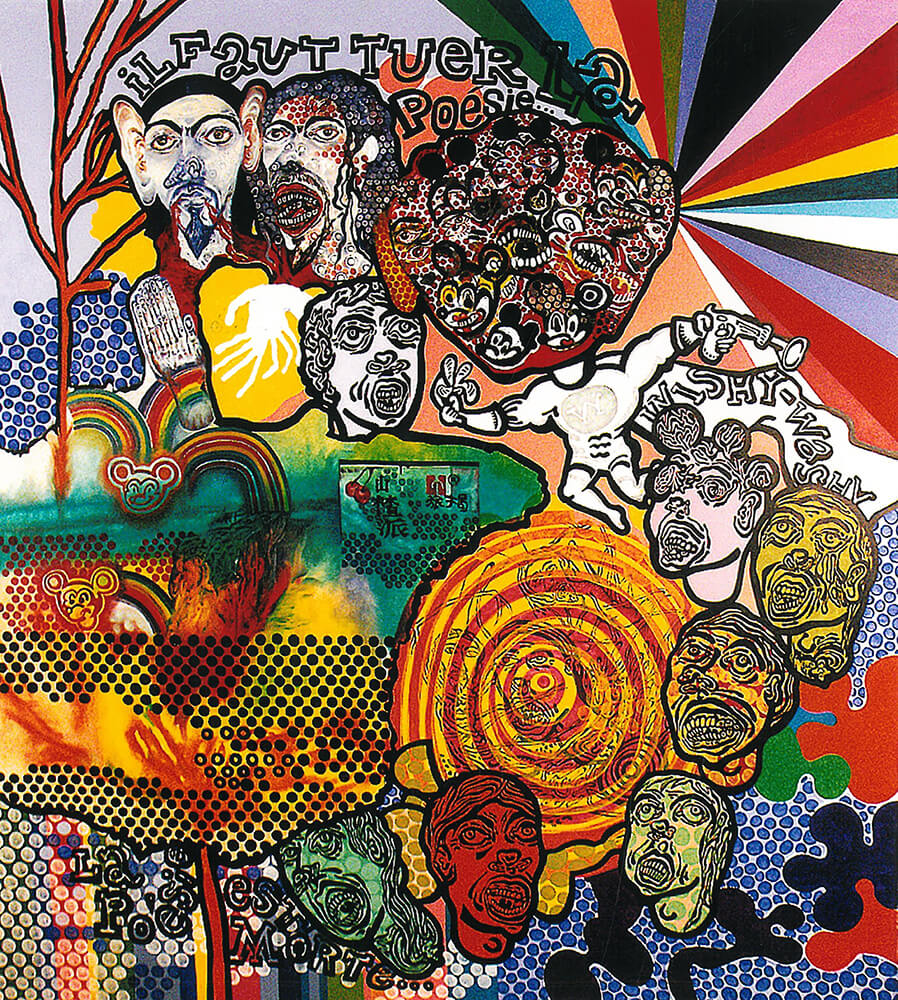

These ideas should be kept in mind when we depart to the discovery of the paintings, drawings and collages that Ivo Moreira has made in the last couple of years and which are presently gathered in this small book. This recommendation is all the more important since the said production has occurred after two diametrically opposed travels (in geographical, cultural and spiritual terms): one that extended over Maharashtra, Goa, Tamil Nadu and Kerala, in India; and another one to New York, on the other side of the world.

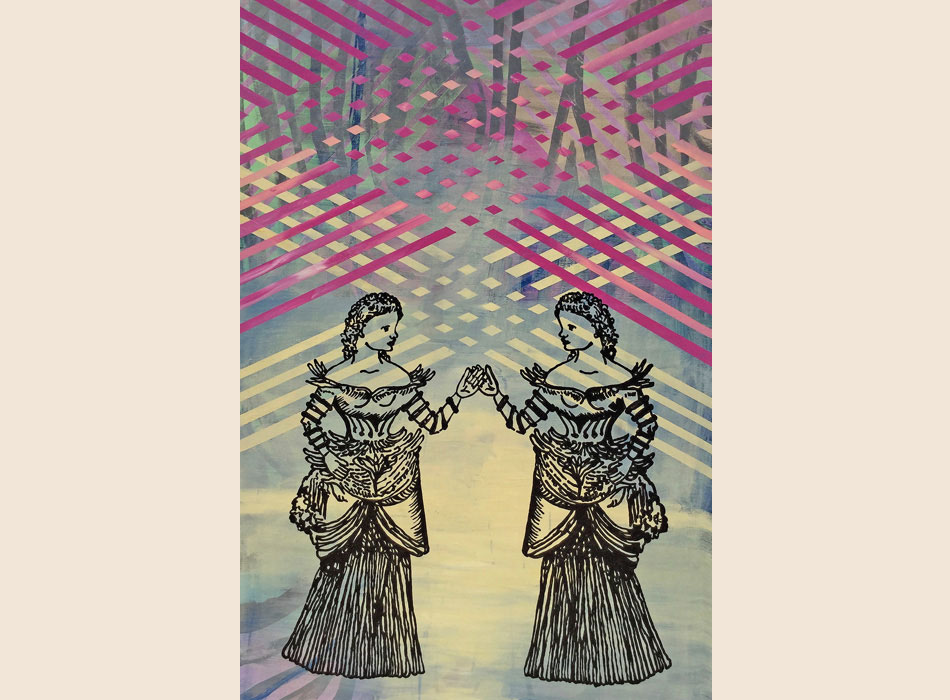

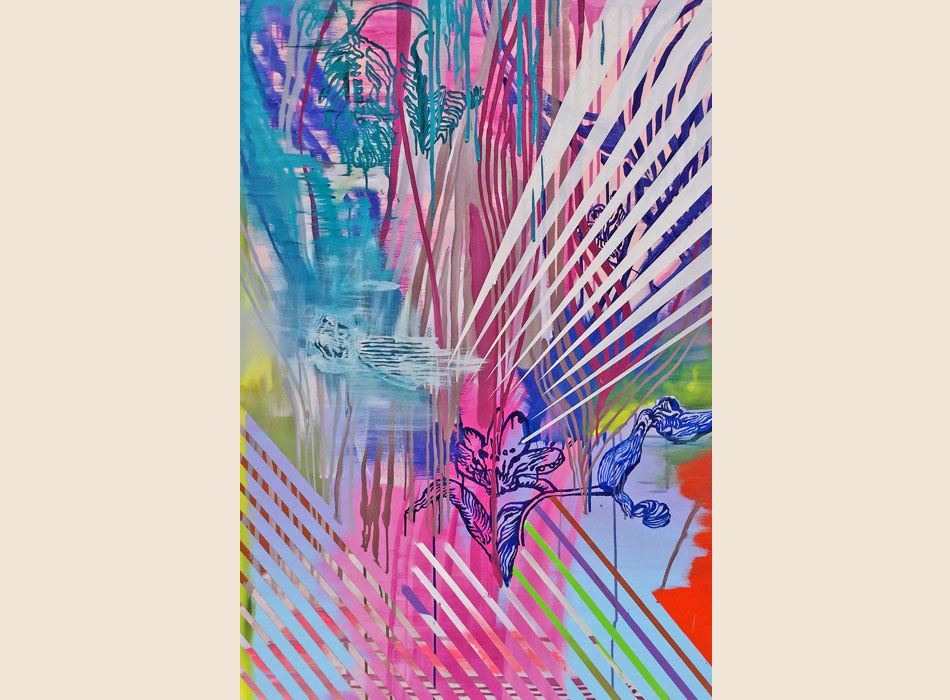

In reality, it would be difficult to find two destinations that are so clearly opposed in every aspect, however, both one and the other have left deep marks on the artist’s recent works, contributing to a painting that crosses over distinct cultural contexts, different practices and methodologies, and that has as one of its most enduring characteristics a cosmopolitism that becomes ability to sort out and organize presences that are contradictory amongst themselves.

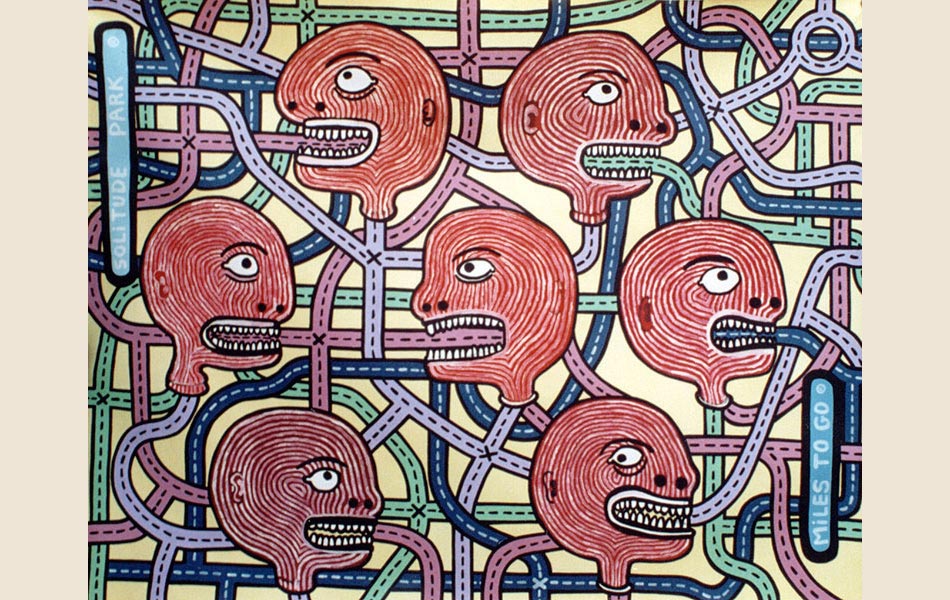

But there is another aspect that we have to link with the idea of transit and travel in the work of Ivo Moreira, and which is the drawing whilst structuring methodology that is always present as much in his paintings as in his collages, and naturally in his very drawings, which are now presented as a part of this set. Such presence is fundamentally linked with two essential possibilities. The ability of quick annotation allowed by drawing, thus becoming a transitory description that can be reincorporated into other contexts and moreover, the fact that all his compositions are structured through drawing.

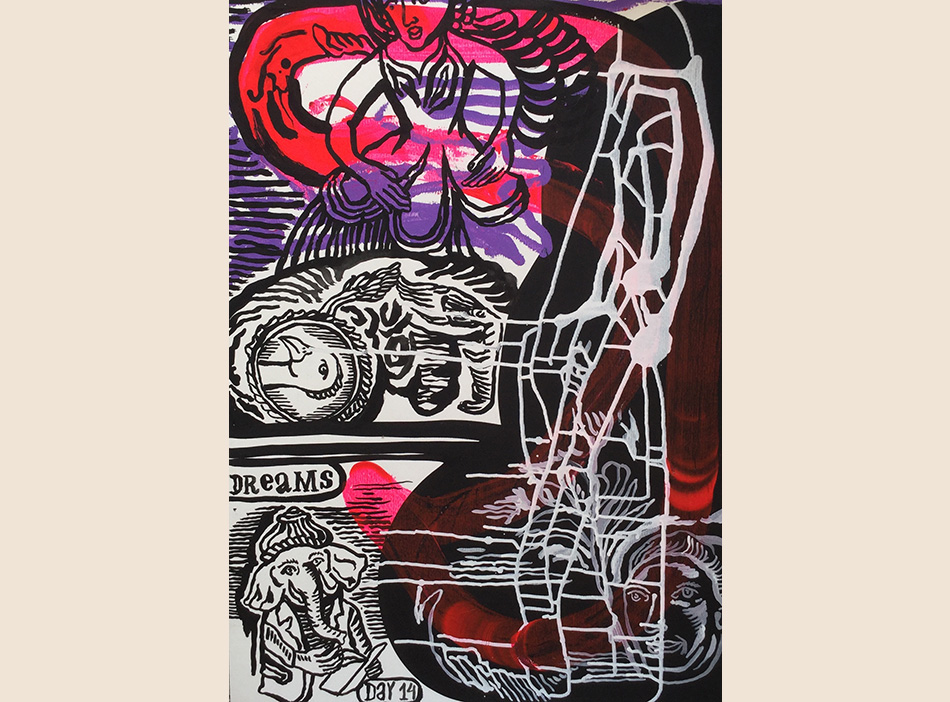

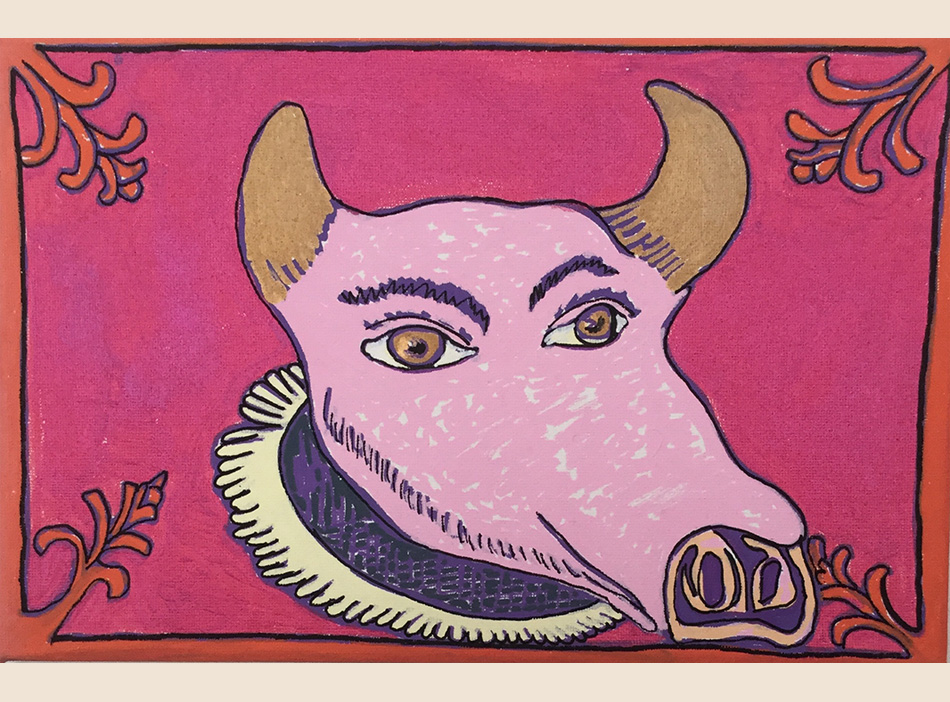

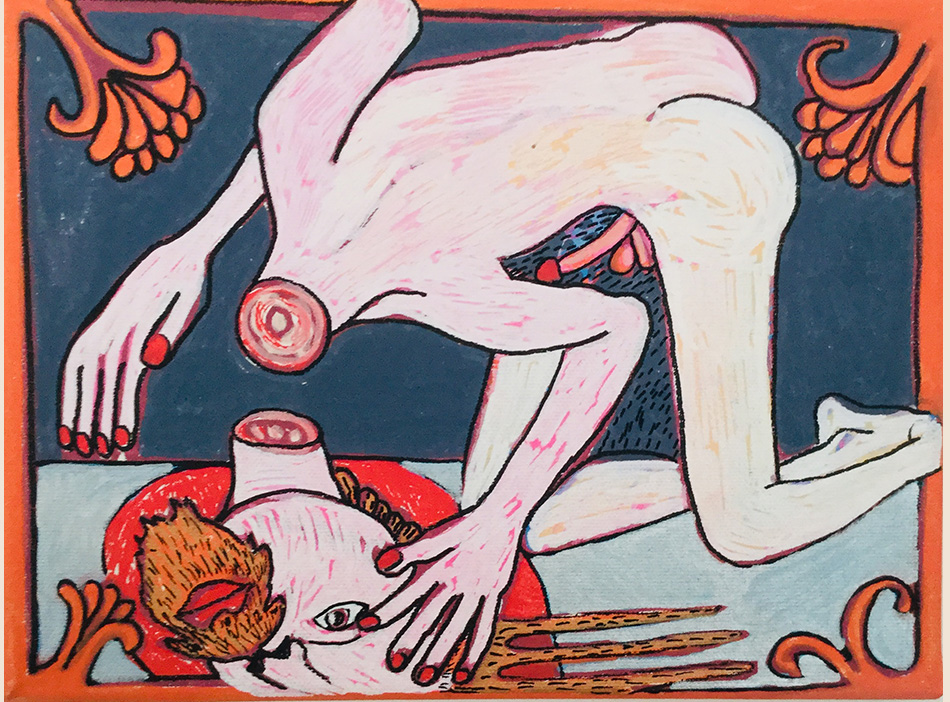

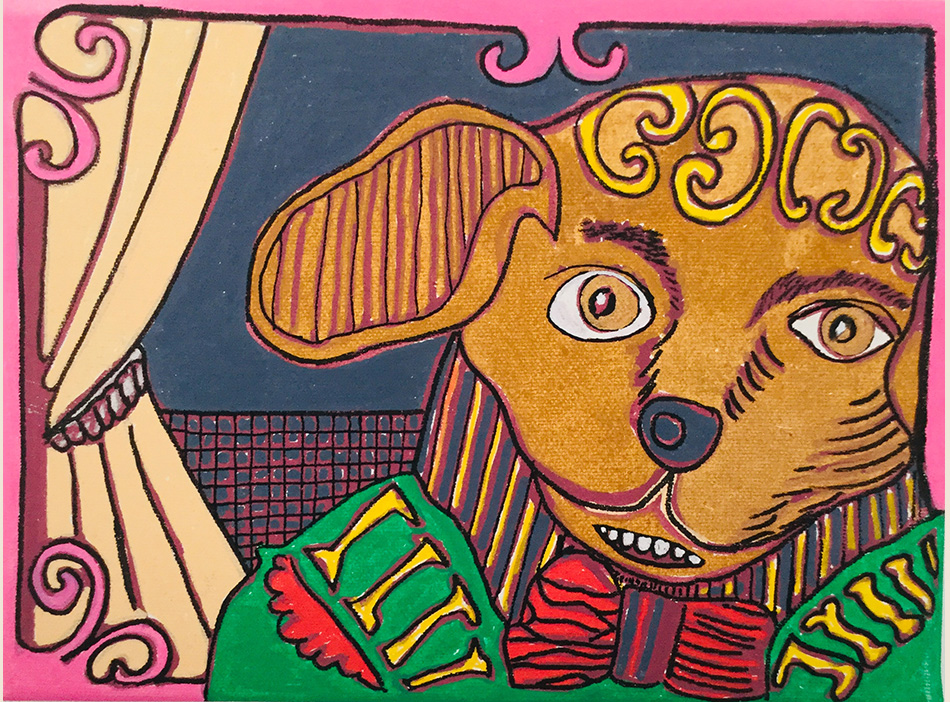

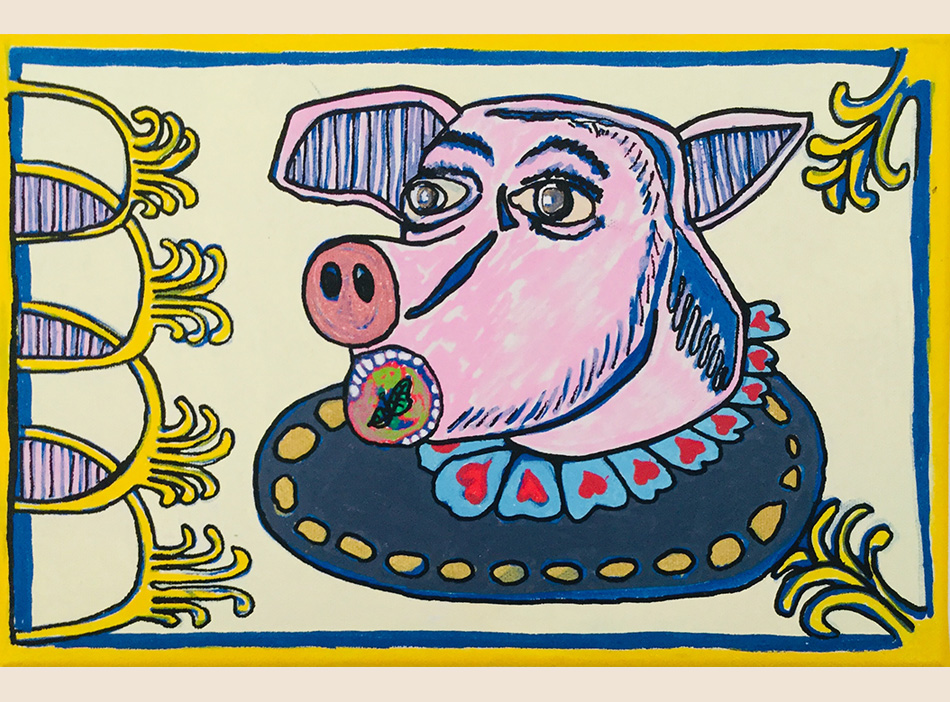

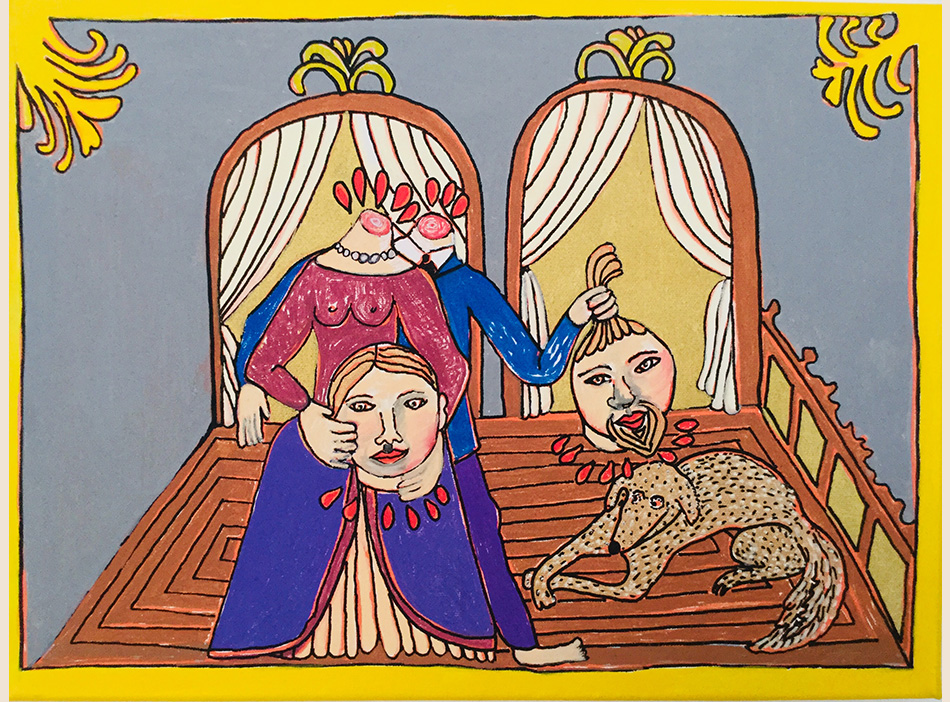

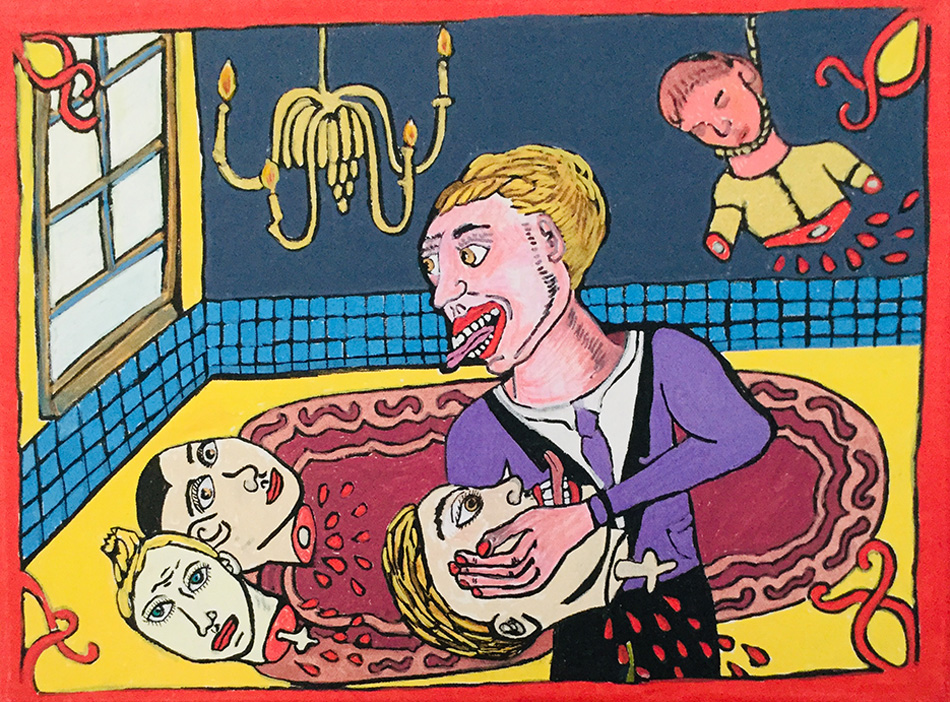

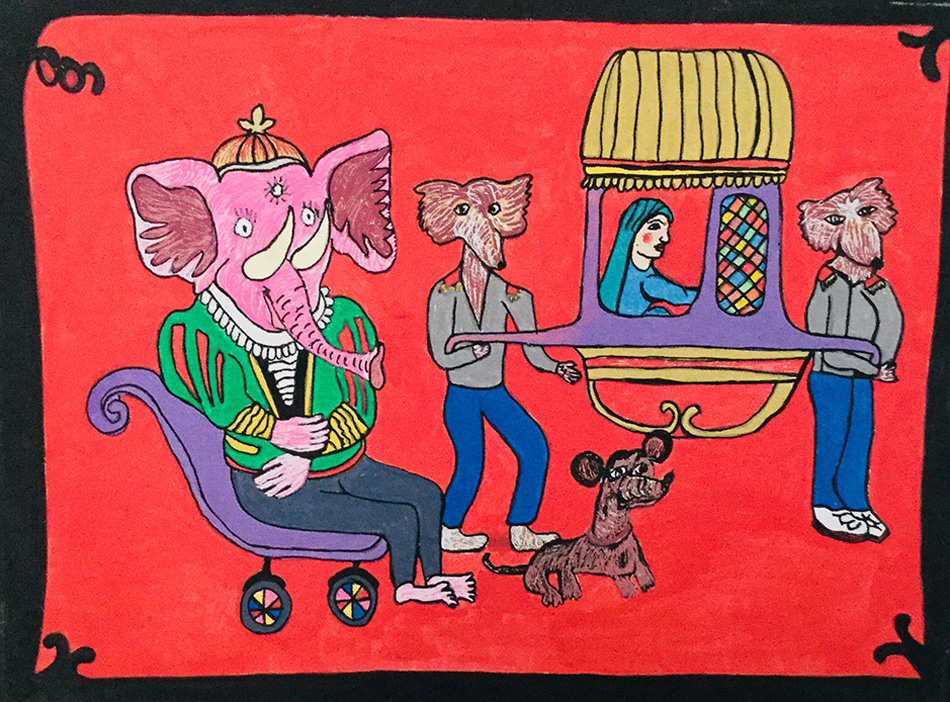

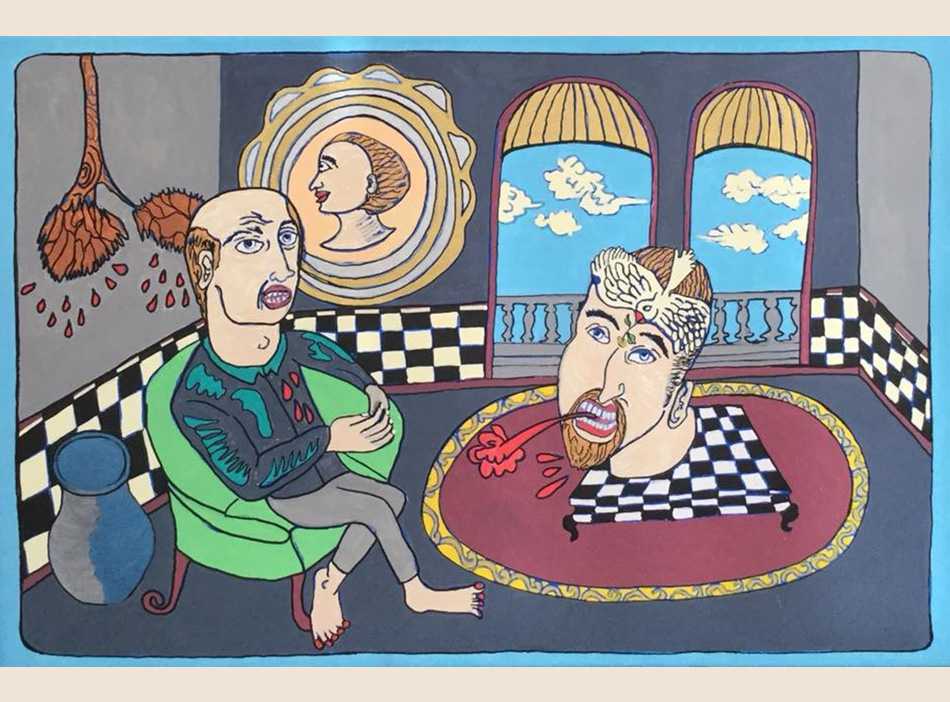

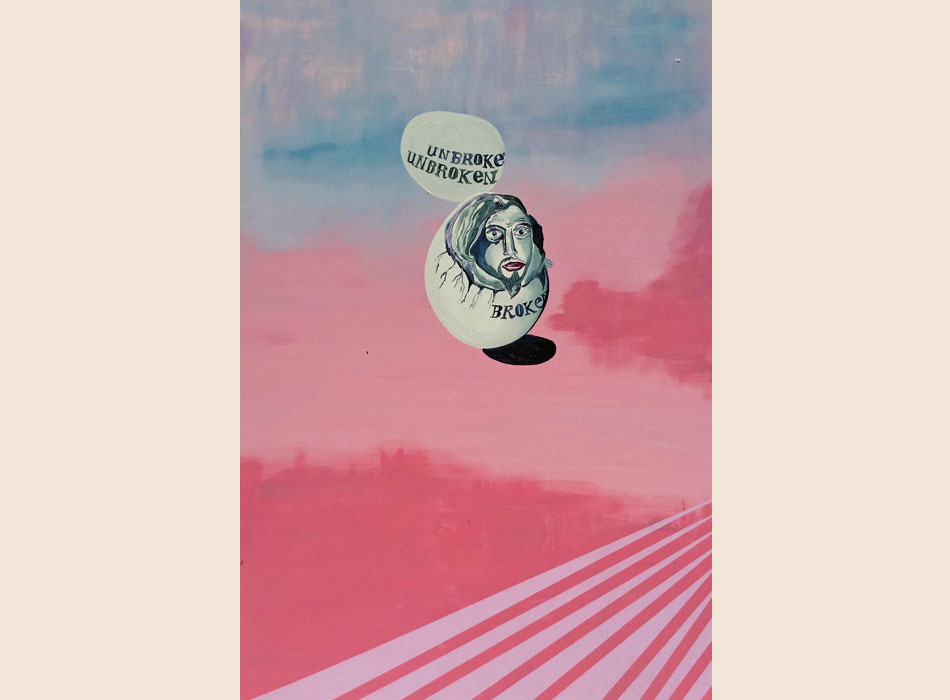

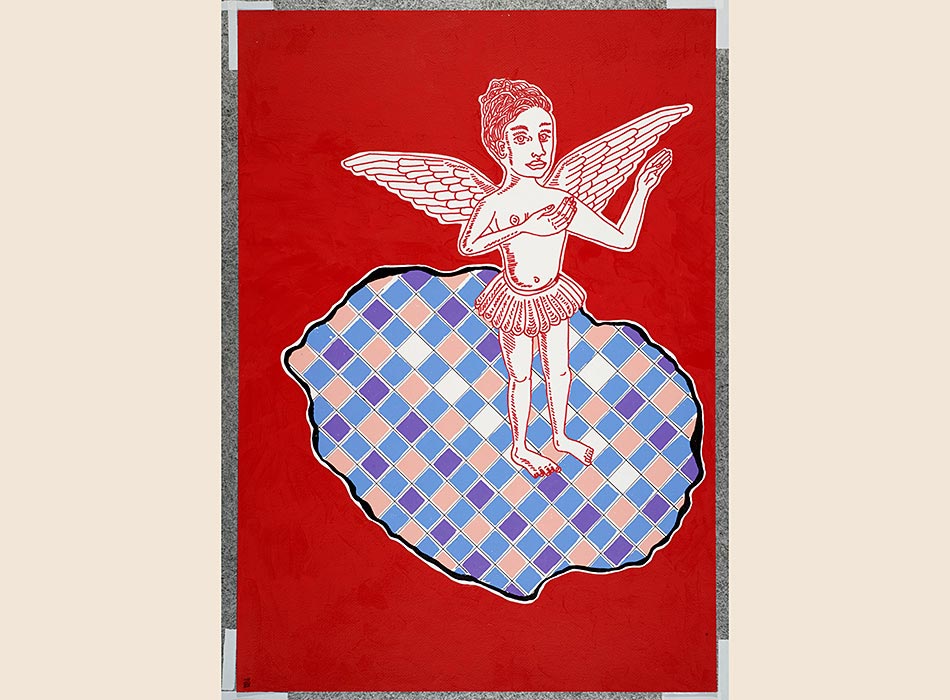

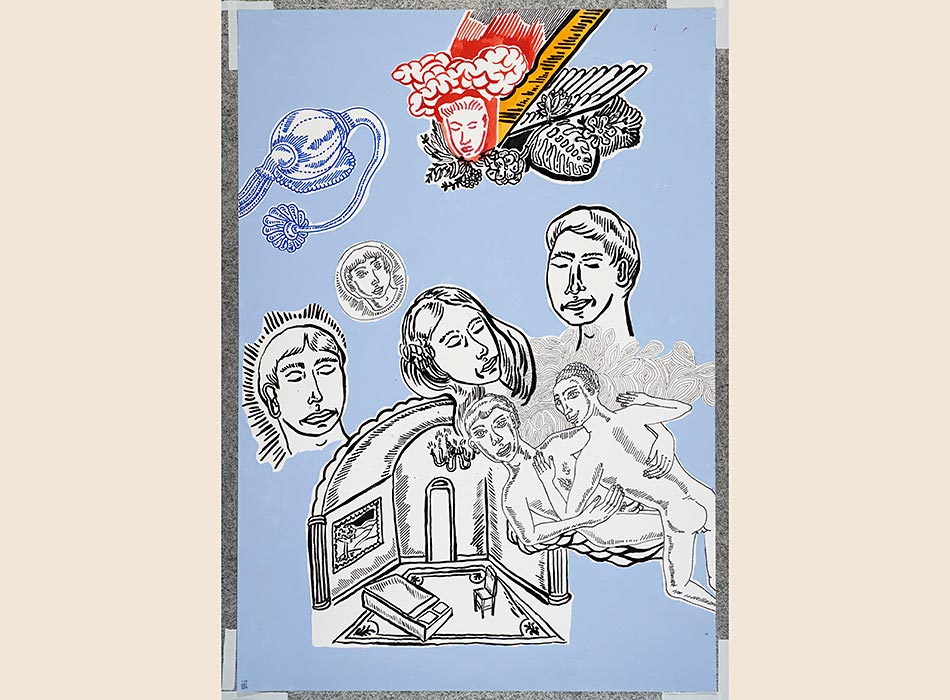

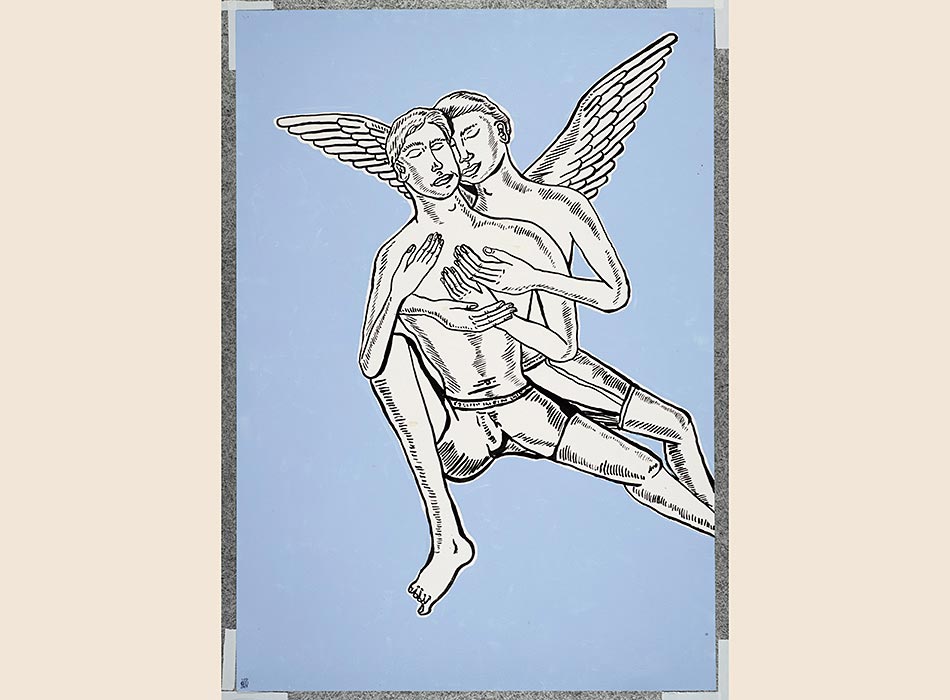

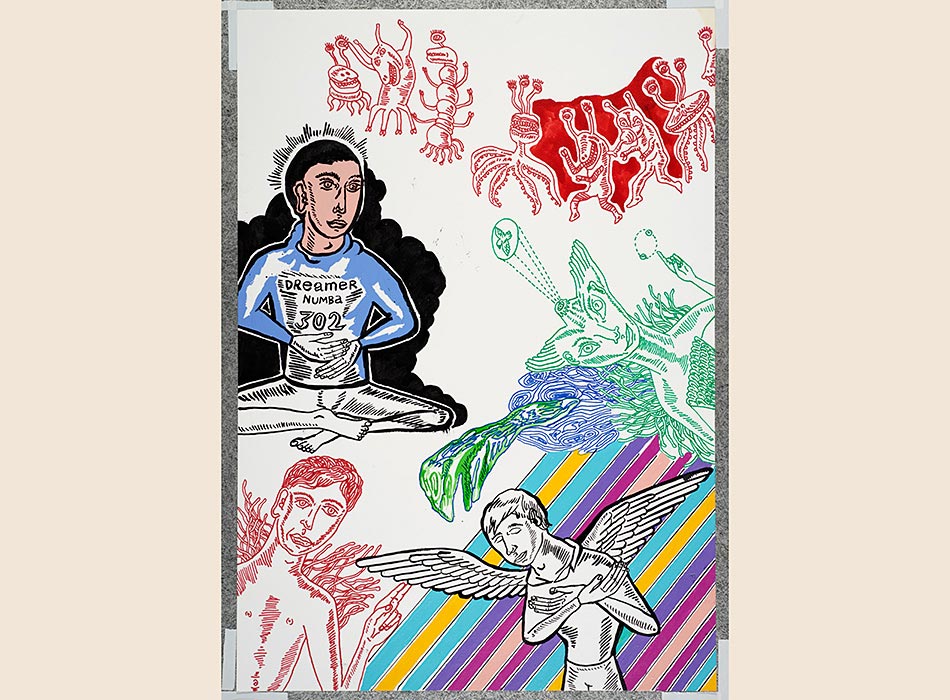

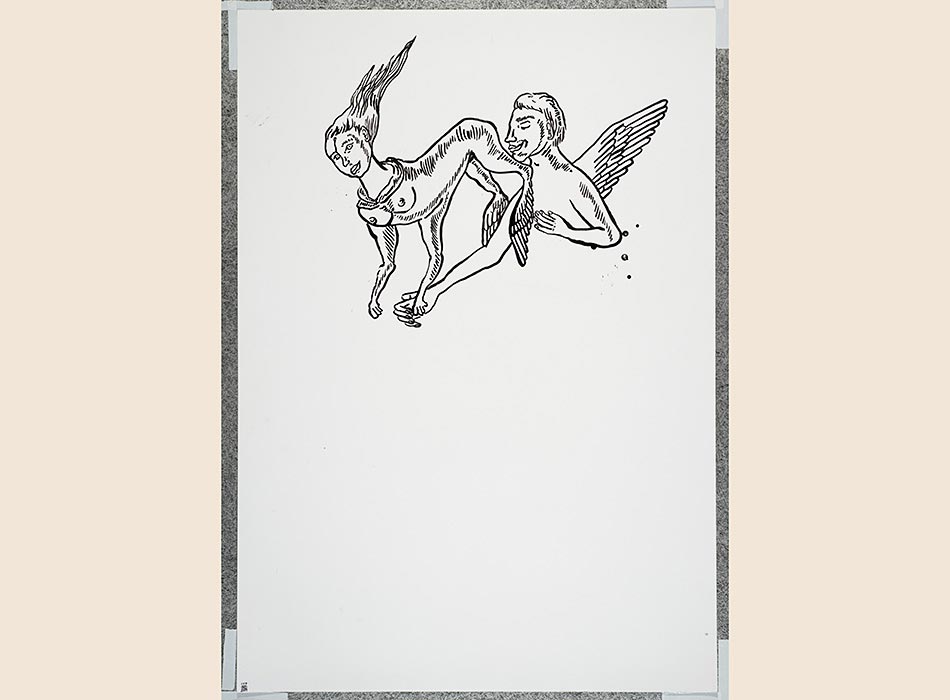

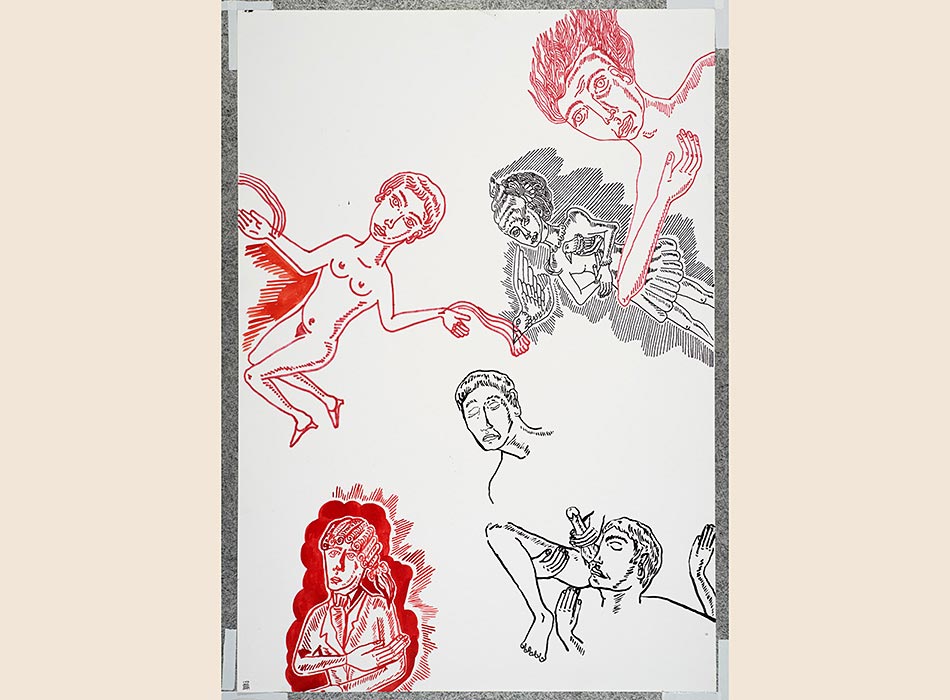

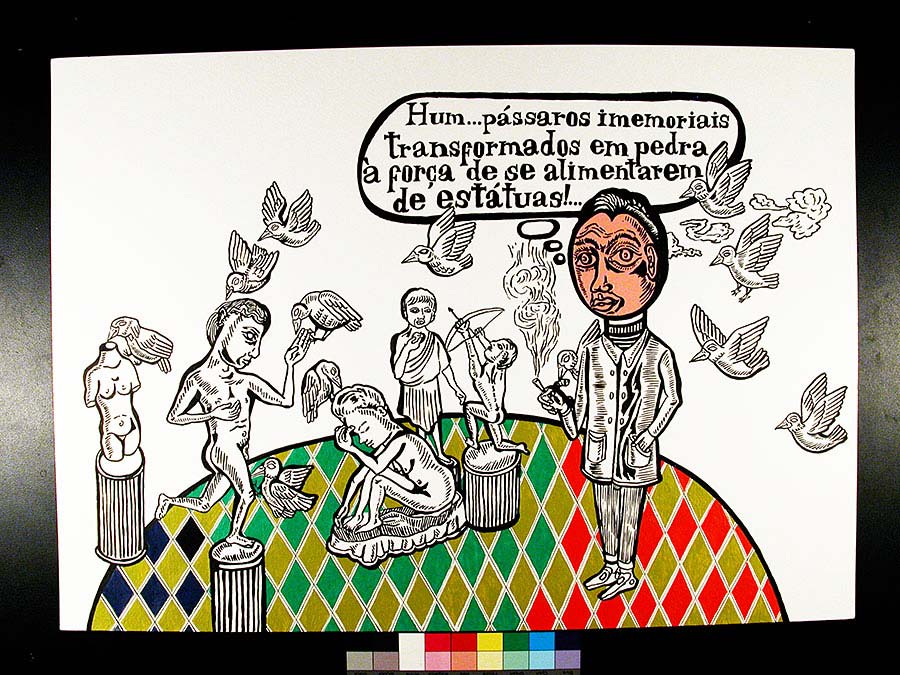

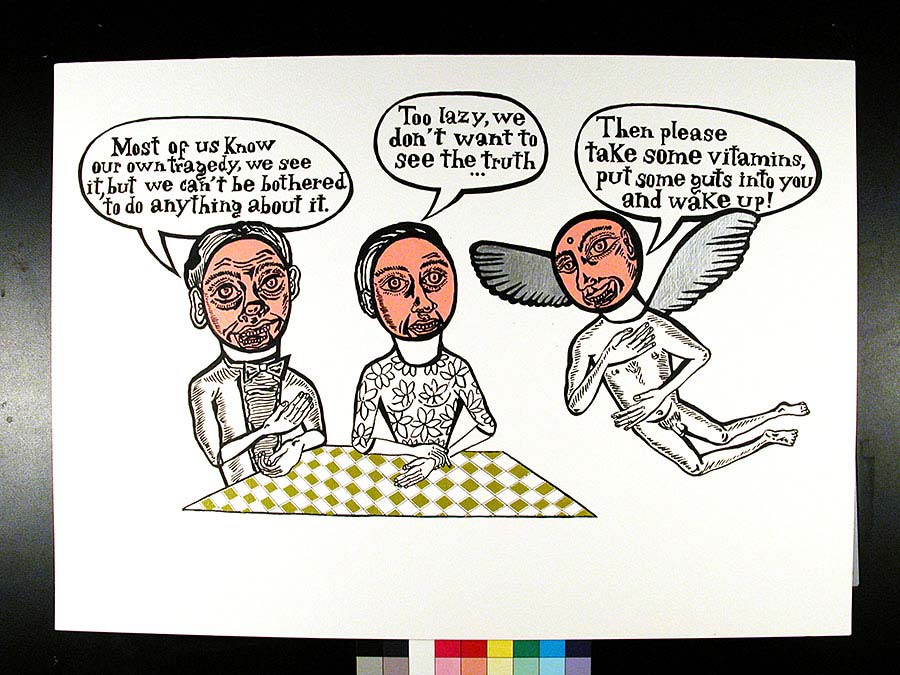

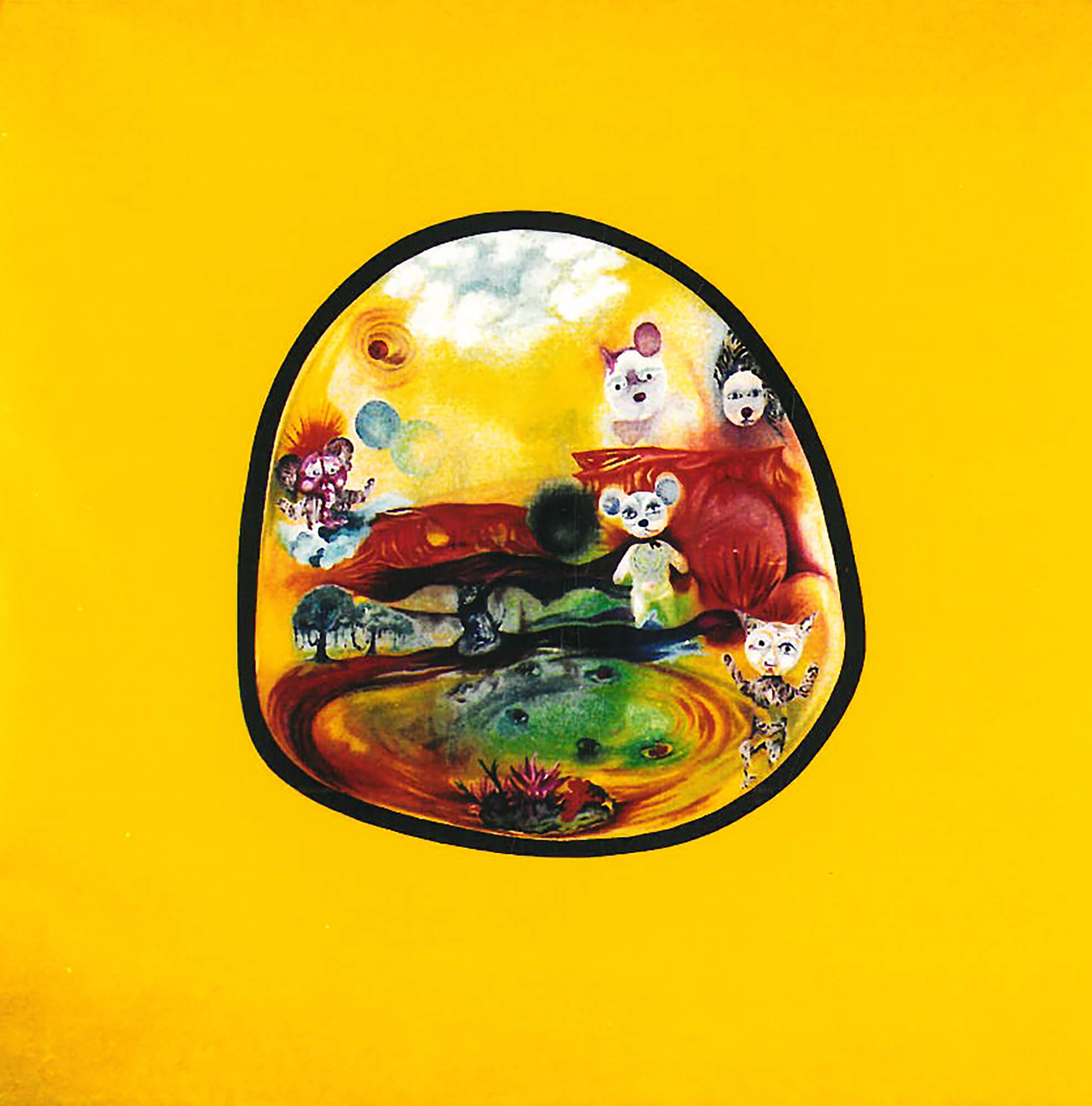

This latter factor immediately sets the painting of Ivo apart from any illusionism in the sense of a possible attachment to the perceivable “real”, at the same time reinforcing his work’s design whilst a sort of mental diary, simultaneously imagined and lived, which can be inhabited by people made of flesh and bone but also by angels and gods or animals that take on human characteristics.

Likewise, it is this assumption of fantasy as legitimate mental life, which can make the most cynical blush, that allows him to cross over culturally distinct territories and to leave biographical marks on them, which should not be taken literally but rather as staged images with different reading degrees.

But his travel experience is also rooted here whilst an emotional and existential itinerary which does not exclude aesthetics in his passage through things, people and places. And many times such aesthetic dimension which appears to be so indefinable is what memory recalls from the places which we go through; a colour, an outline of the scenery, a smell, a sound, or a song in a foreign and incomprehensible language. This is what seems to be said by paintings such as Silence is

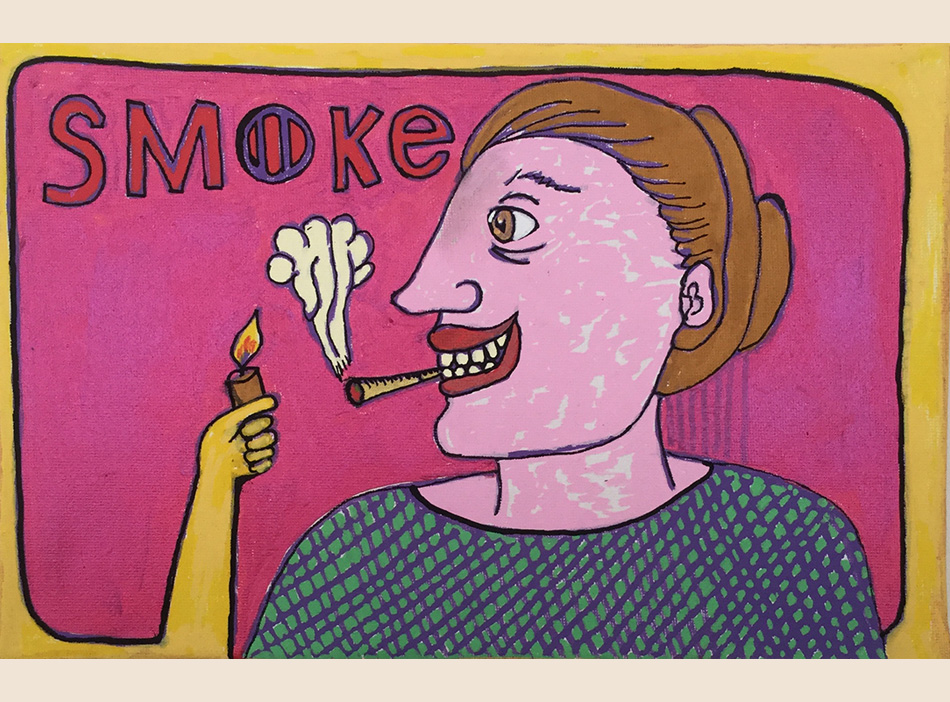

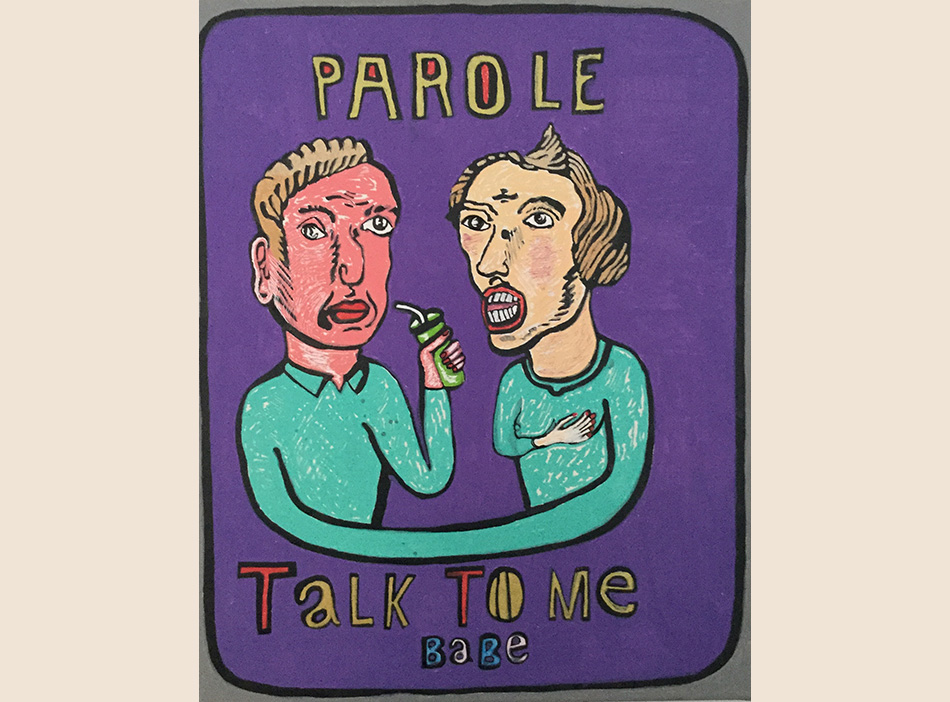

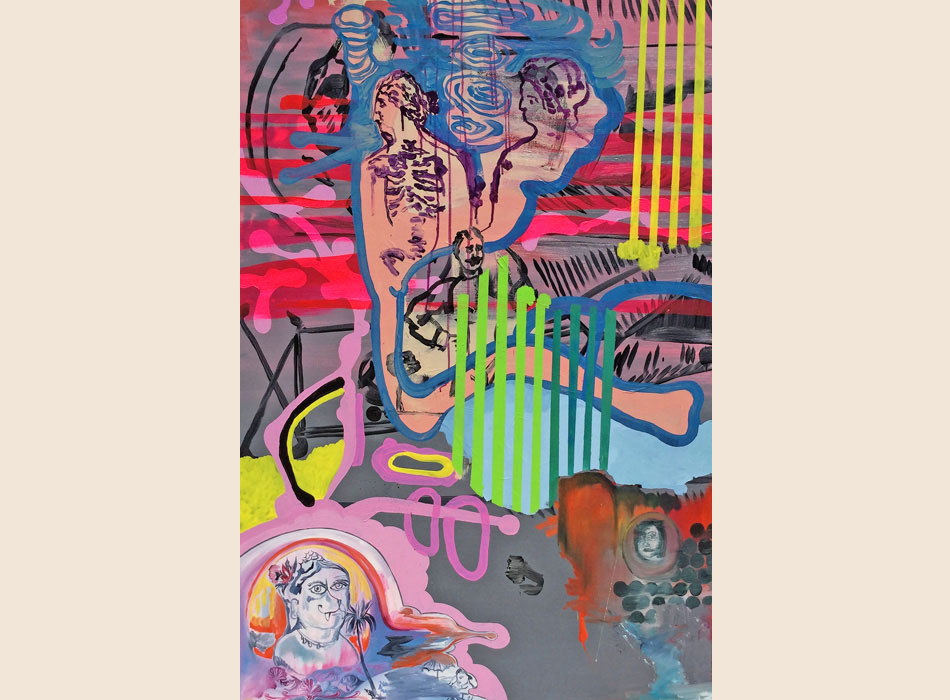

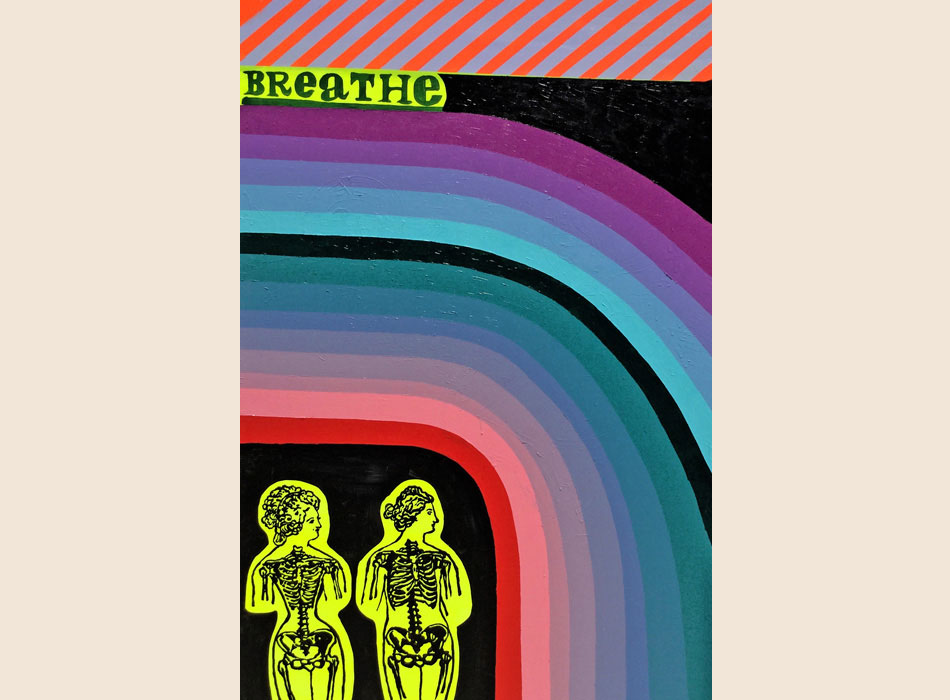

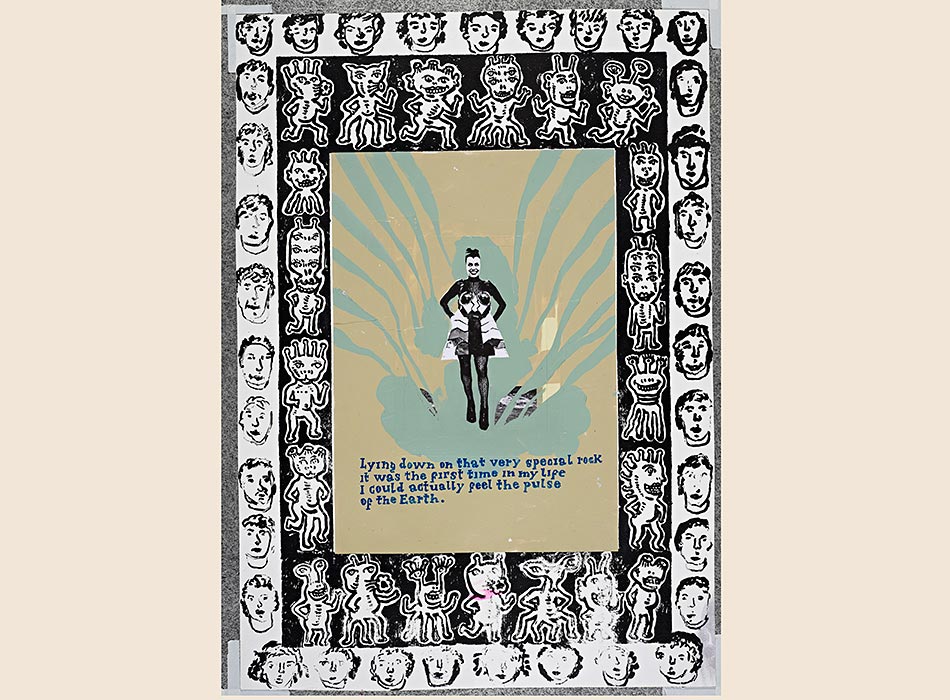

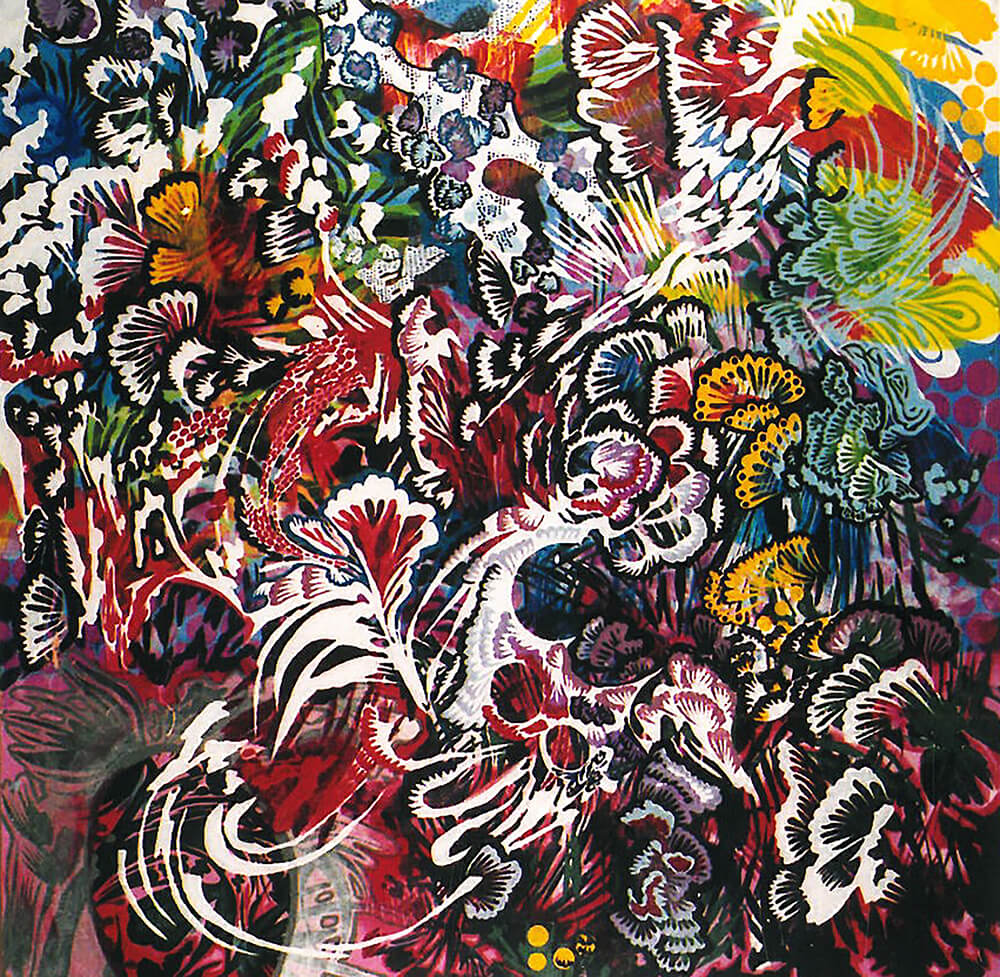

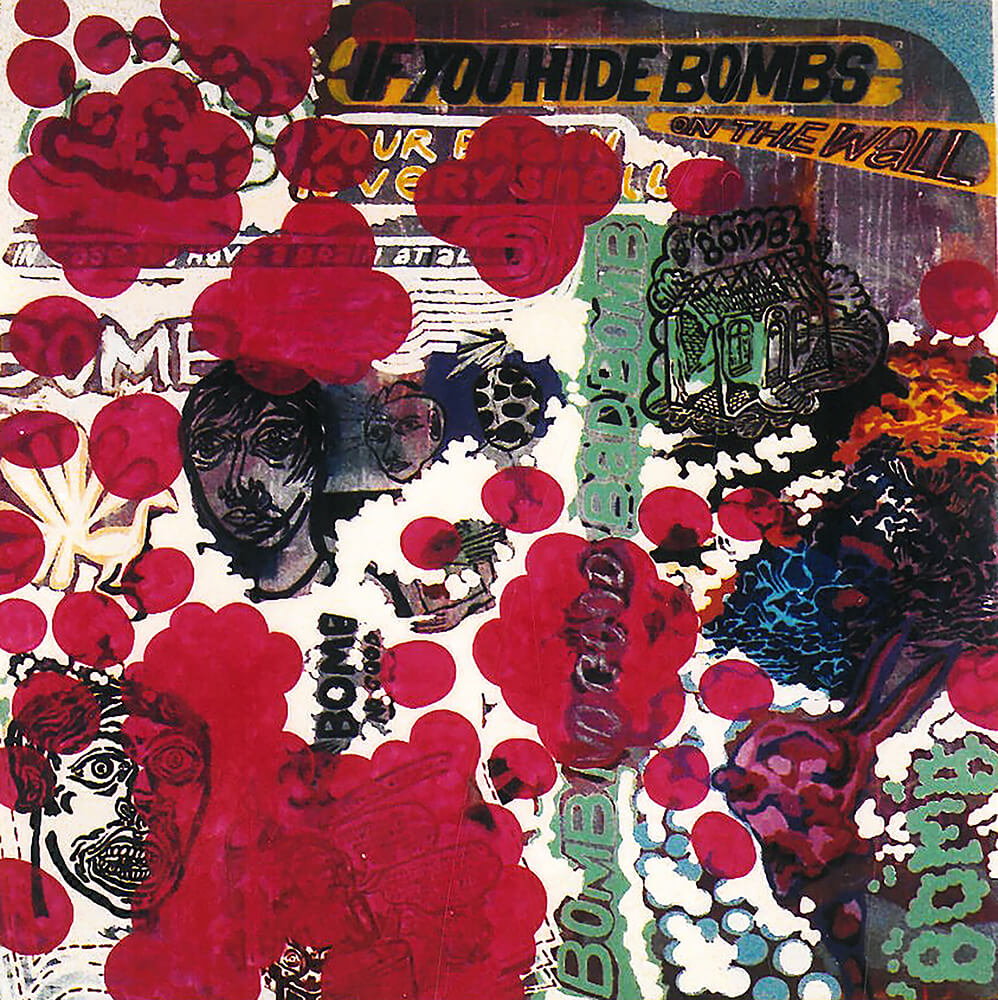

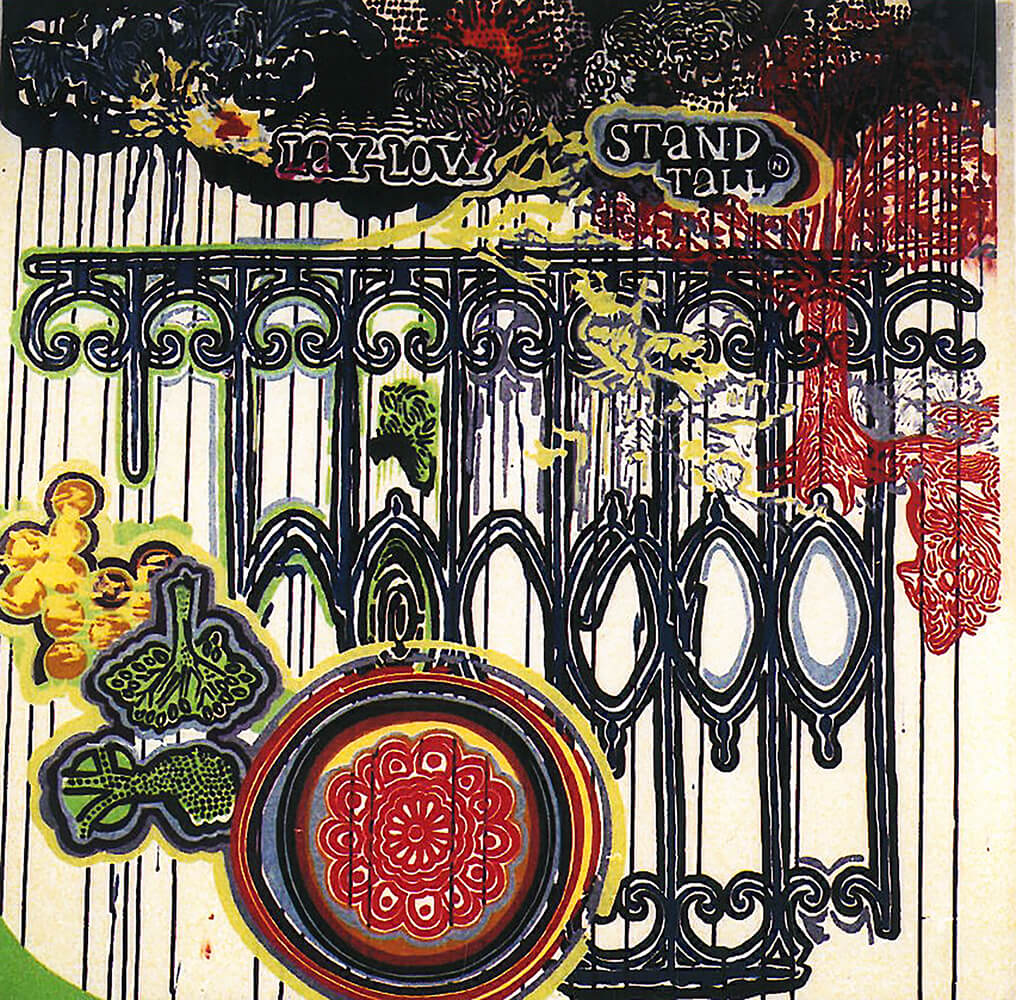

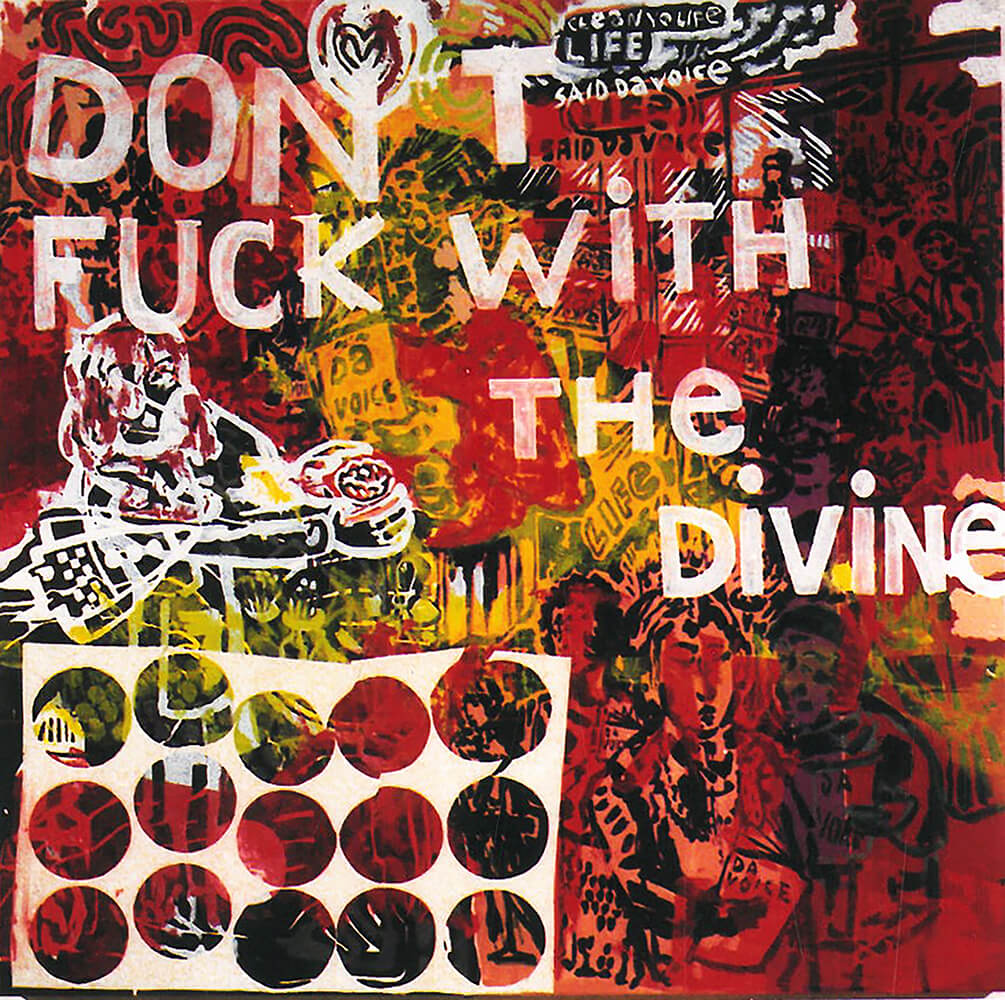

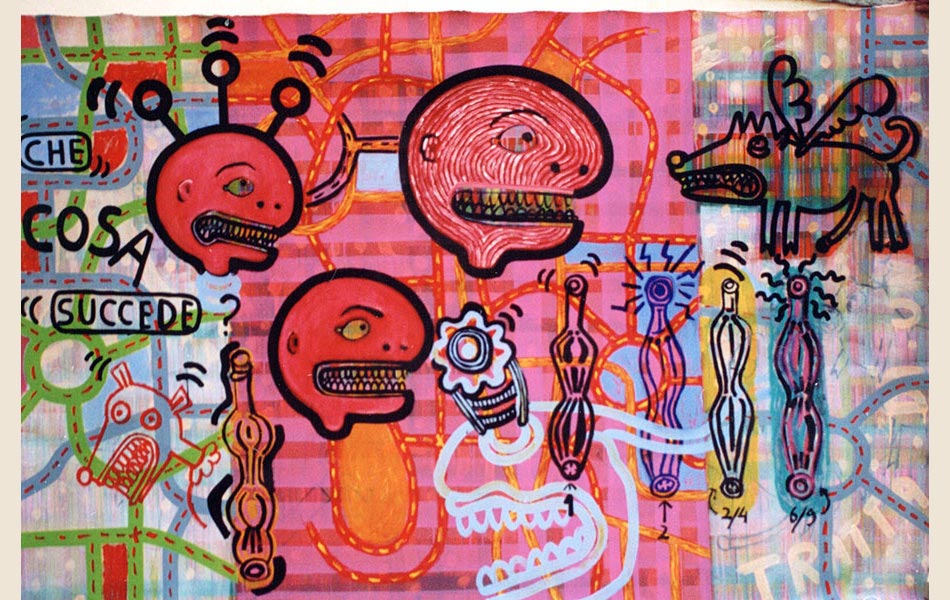

My Salvation in which the vibrancy of the colour and of the forms is as important as the spiritual calling; or in others, such as Post Romantic Euphoria in Disguise in which the decorative and narrative dimensions become unified in a psychedelic ambience with an intense chromatic profusion. To present, to tell, to induce a sensation or an ambience are ultimately not very different things in the painting of Ivo Moreira. That is notorious in the manner how he uses language which further to its verbal message is also and always drawing, but also in the manner how certain stylistic elements are introduced into his painting.

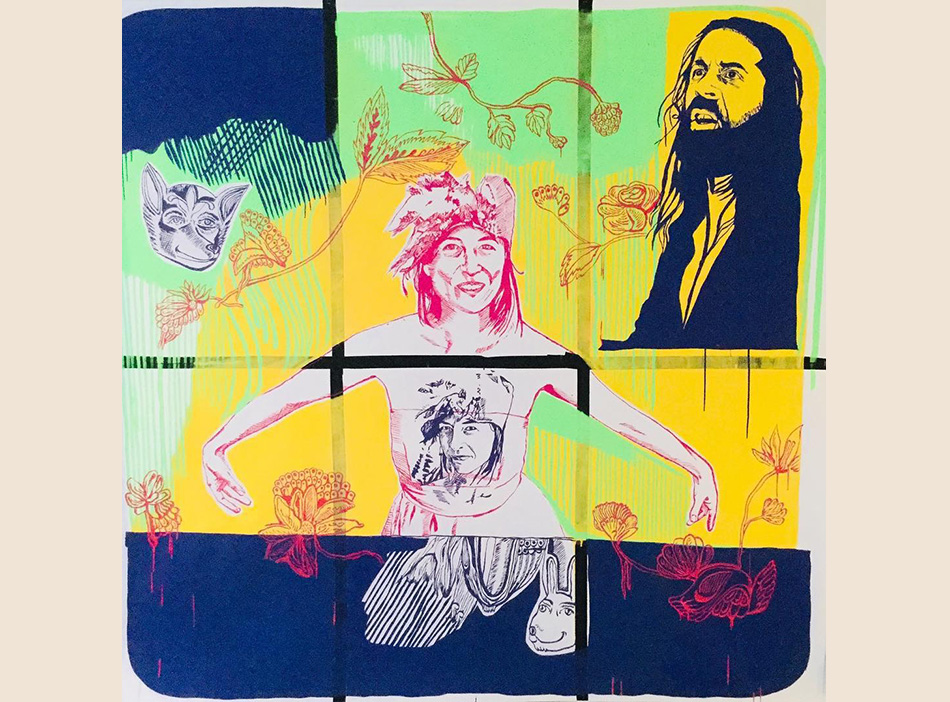

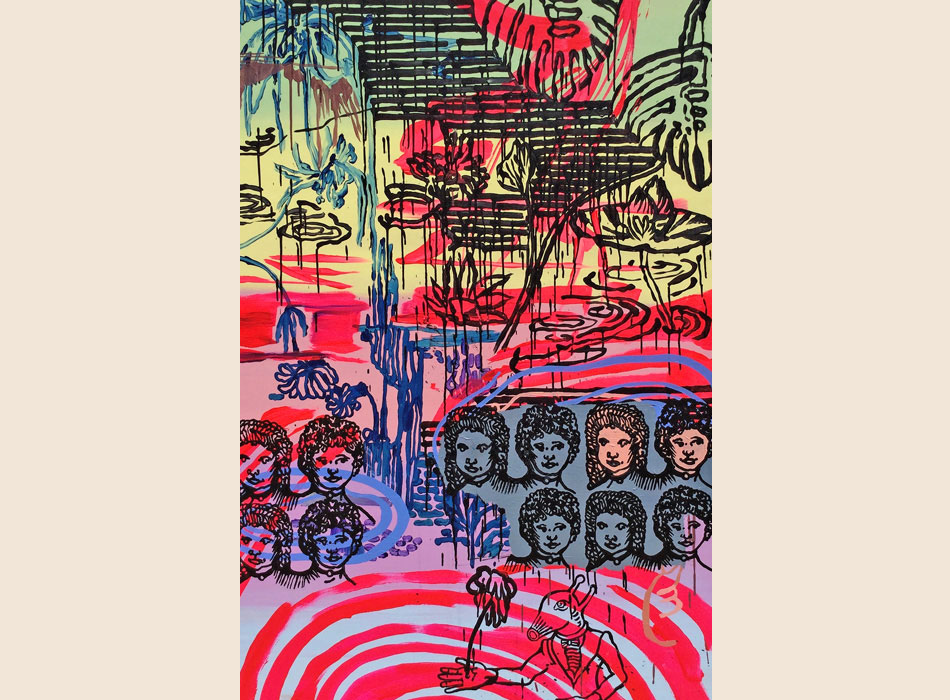

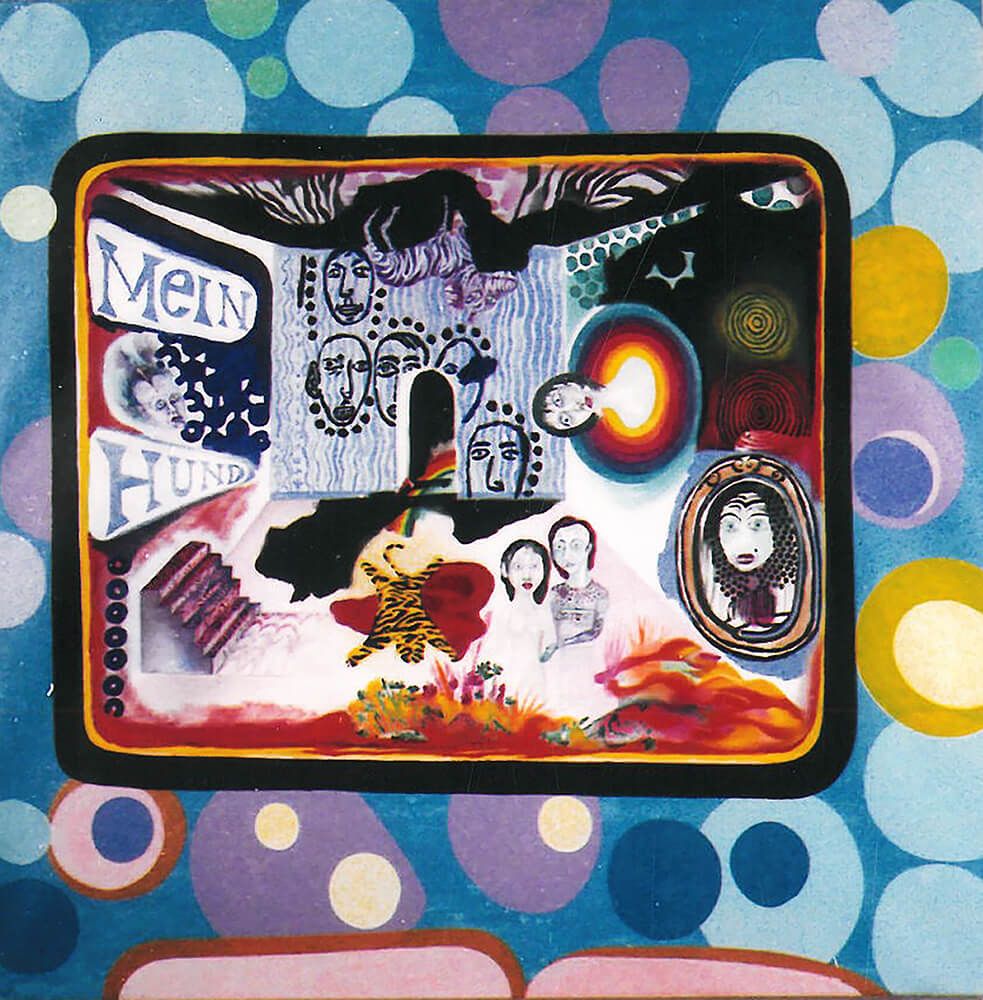

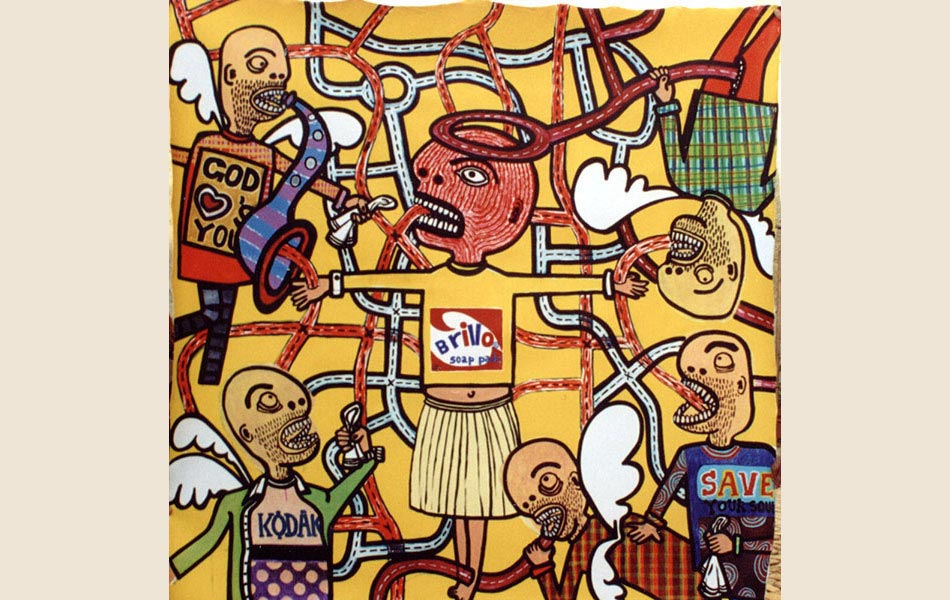

For instance, it is curious how Ivo resorts to structures that we associate with decorative contexts to establish gradations, sensorial intensities or emotional affiliations. We can see this in Andy and Evelyn Before Eating an Apple Pie where a sort of rectangular frame is set with Andy’s and Evelyn’s faces idyllically inserted, or in the geometrical and almost Mondrianesc arrangement where fish move in Under the Sea. But also in his paintings where such two characteristics are more overtly mingled and that together better define this type of painting: a certain gothic primitivism curiously able to be placed alongside the contemporary urban art of graffiti, and a sense of formal synthesis close to Pop culture.

In respect of what we designate by primitivism, it is actually an effect of determination of the image which does in no way correspond to any form of naturalism or of watching reality such as we see it. Such anti-retinal element specially in a painting that remains essentially figurative allows to organize the reality therein presented according to criteria that do not correspond to its mere physical organization. By playing with proportion, ignoring the laws of gravity and introducing a certain malleability in the figures’ morphology or in the definition of the spaces that surround them, and as we have already said, Ivo Moreira chooses to offer us a space that is mainly a mental construction. In his case, this means abdicating from an easiness of recognition of the world as a perceivable reality, which is so comfortable for the observer, in favour of the expression of a subjectivity that is actively projected over such world.

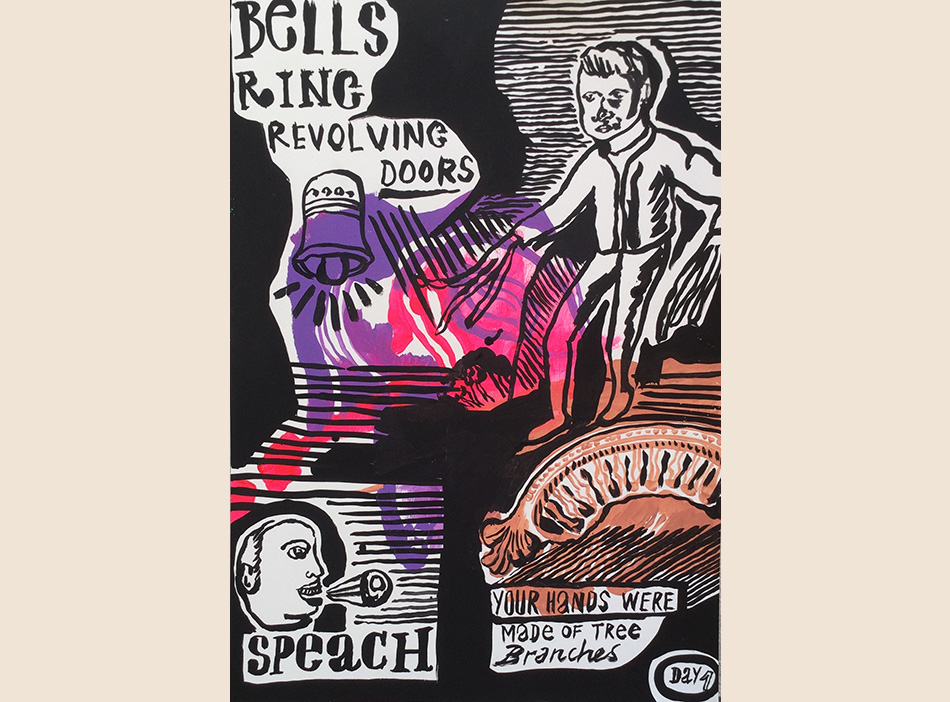

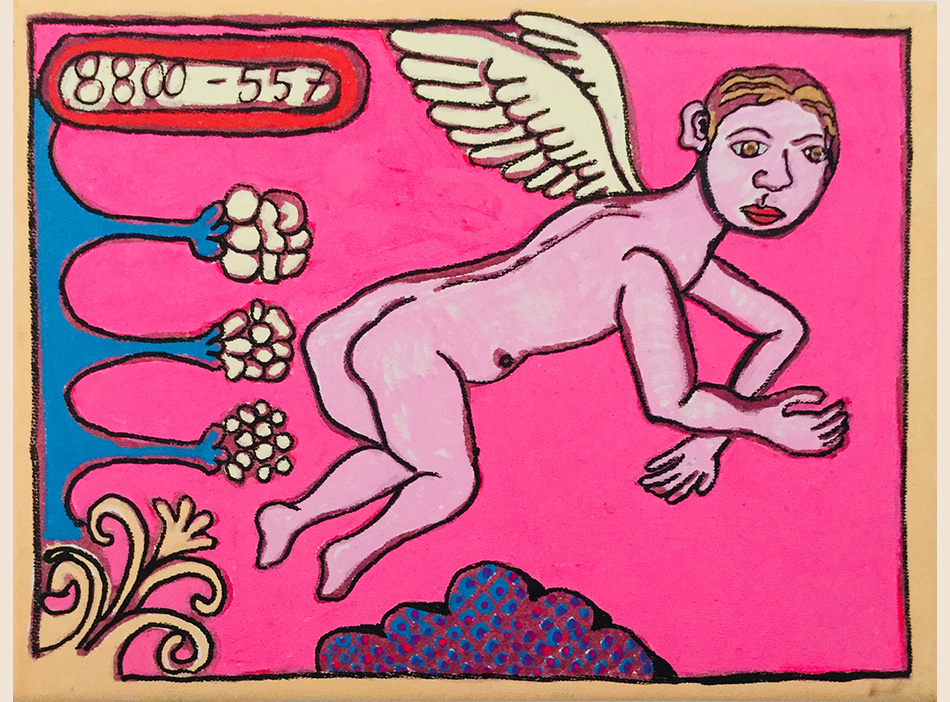

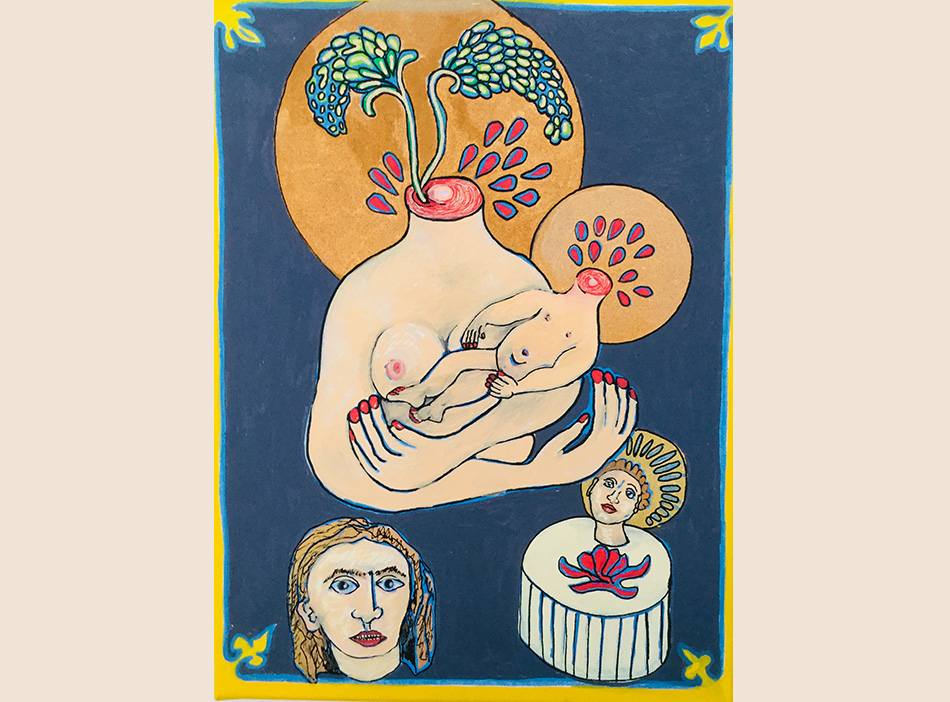

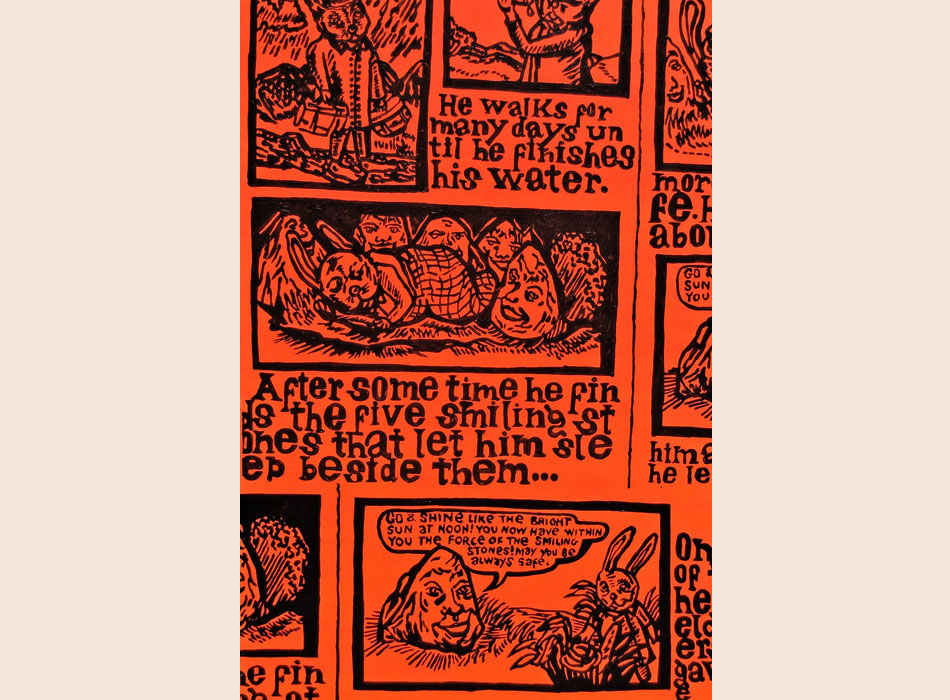

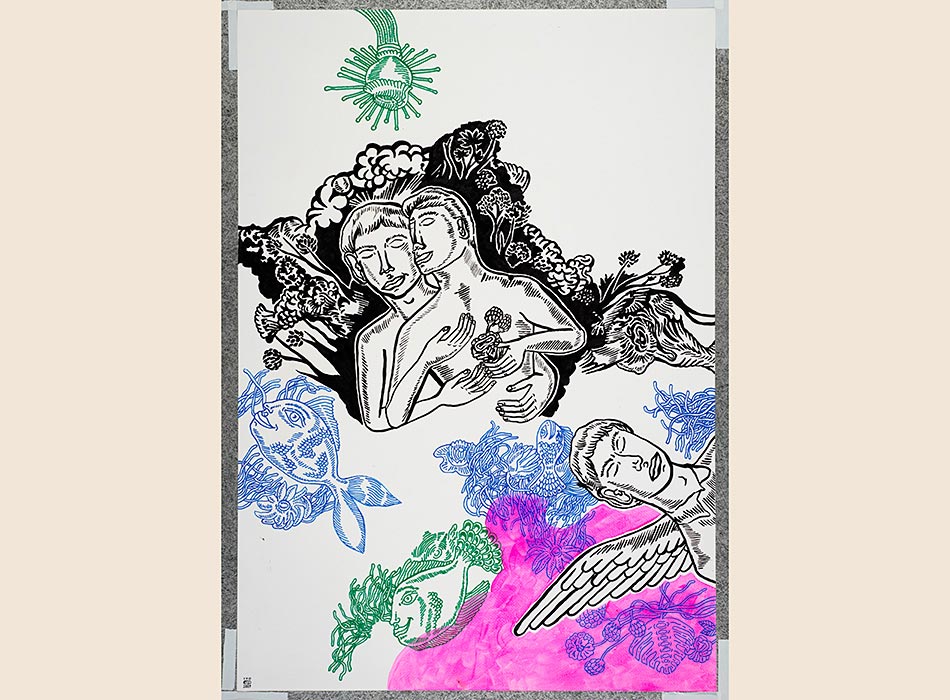

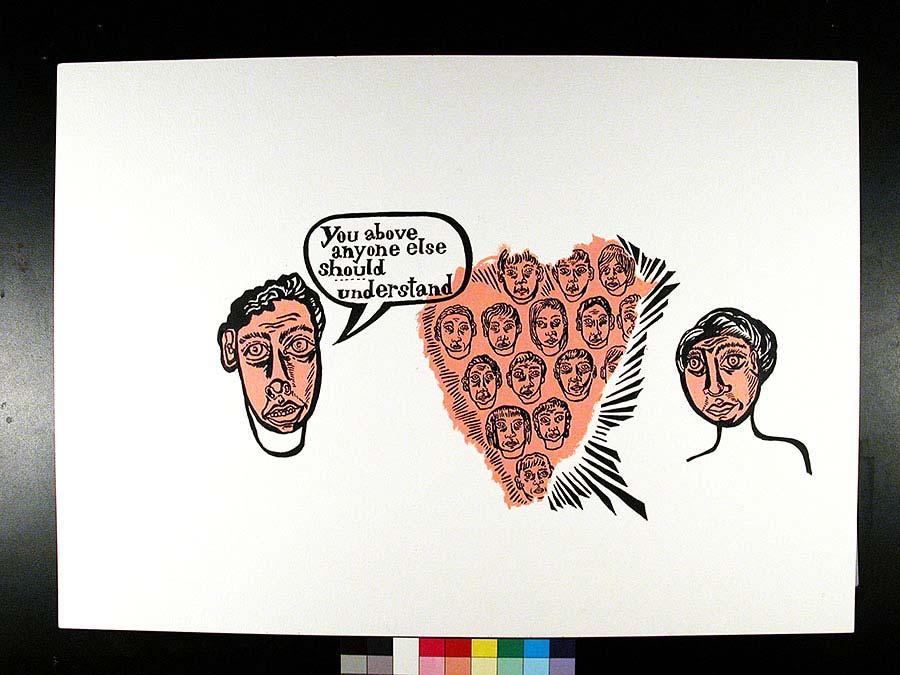

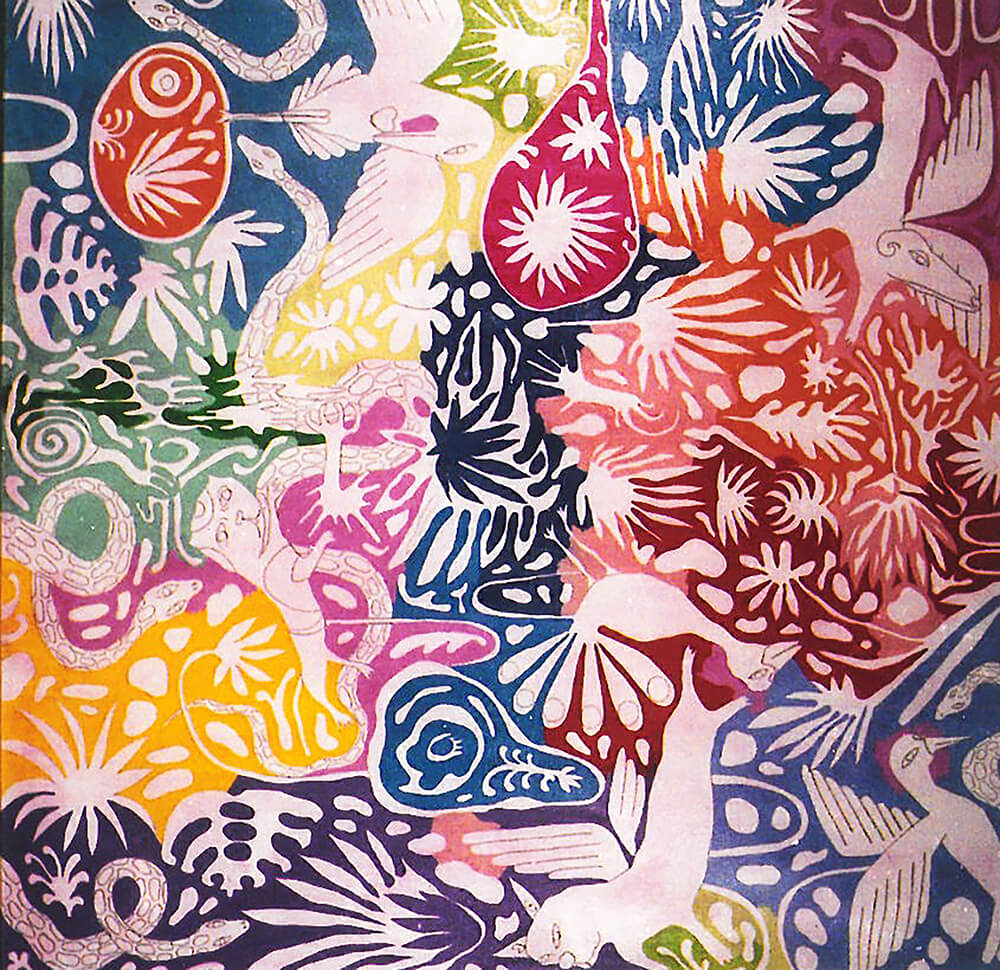

In such sense, he follows a more or less recent tradition which goes back to William de Kooning or Jean Dubuffet, and that is reinvented in German neo-expressionism (Penk, Lupertz), or in American neo-expressionism (Basquiat, Schnabel), setting off from a dimension of the figure that has become obsolete in painting in terms of representation, but revaluated from the point of view of expression. This is what happens, for instance, in the series of large drawings entitled Gifts From Were I’ve Been, in which within an expressive scope reduced to a scarce black and white the painter presents us with a series of surreal figures that fully escape any definition. Decapitated angels holding their own heads, animal-angels, Cyclopes with aureoles, girls with two heads, or men that take other men from within themselves when they open their shirts up, they all make up a gallery of mythical figures of a dreamt and extended humankind alien to any rigid definitions, which the artist wants to set without digression. Further to this trend which we could call iconic and the source of which most certainly lies in different representations of the sacred, Ivo adds another one, which is more fragmentary and directly linked with the ability to dissolve himself in the world of mass society images to withdraw what belongs to him. Instead of analytical comments on how mass media functions, or on the histerized proliferation of contemporary image, he counter-poses a disarmed look but which is capable of hierarchically organizing and reintegrating what he sees.

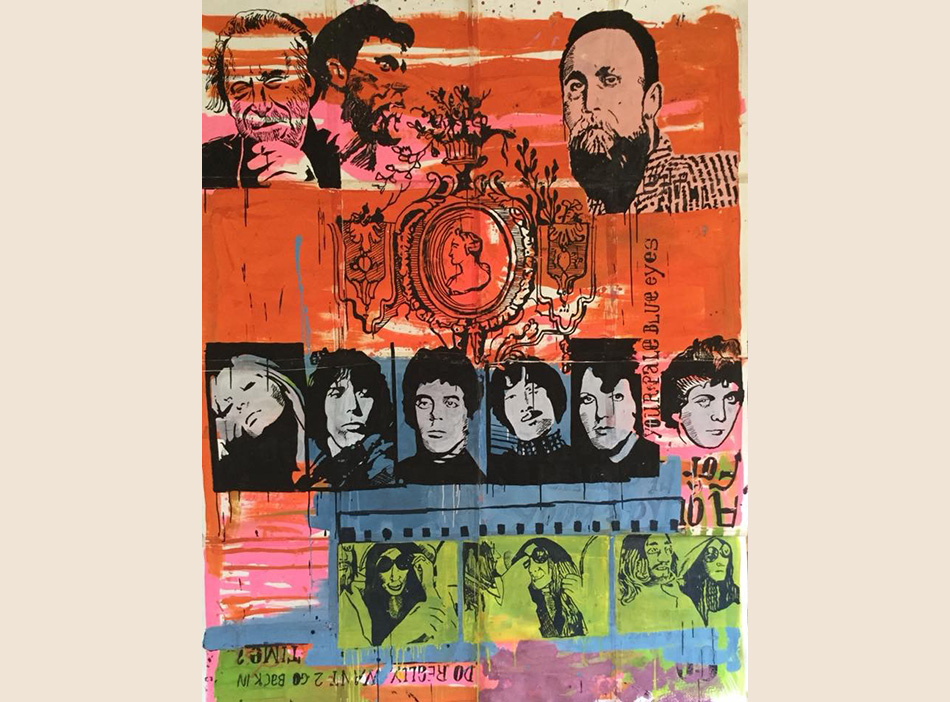

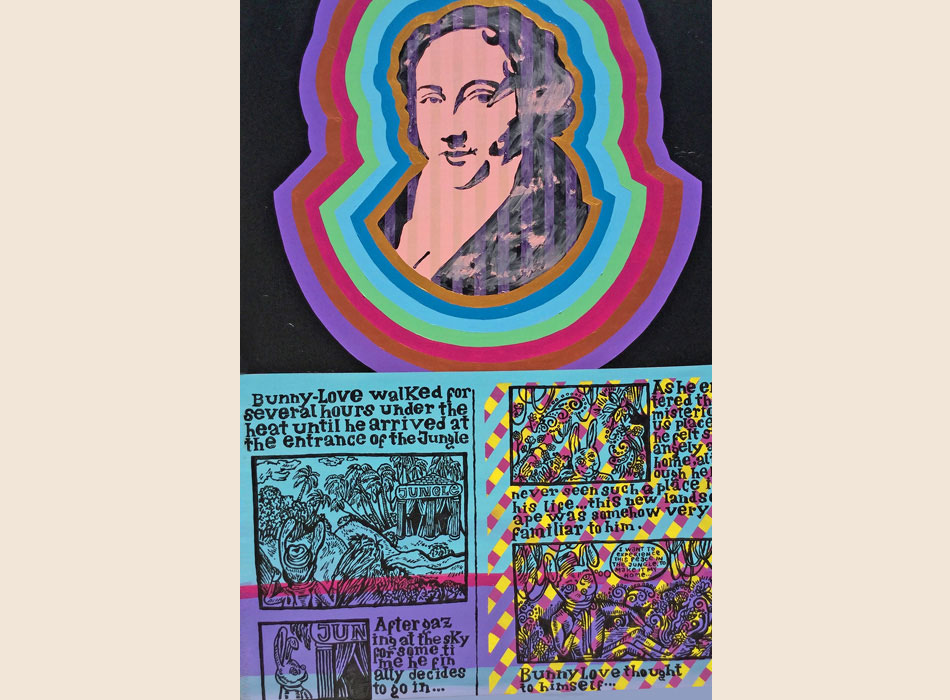

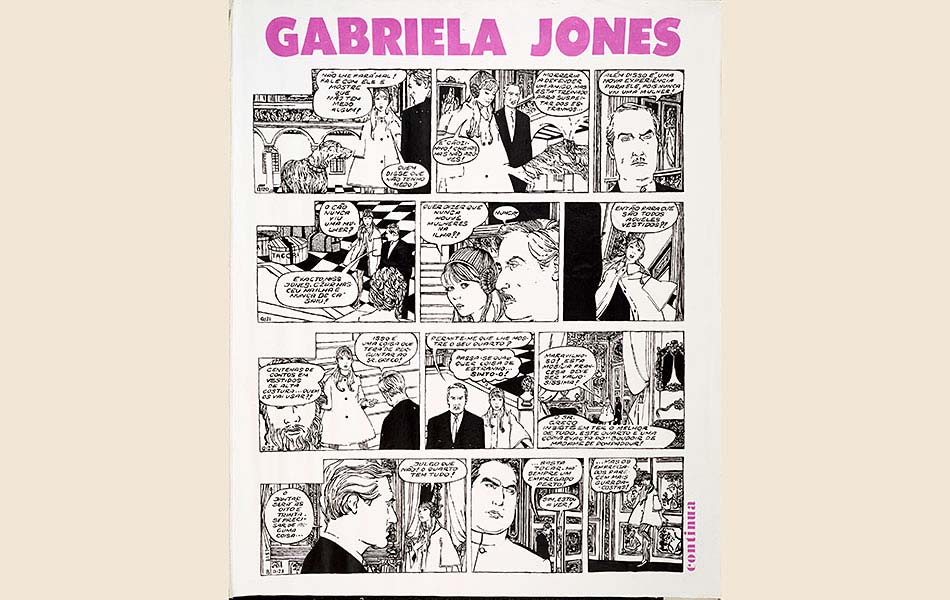

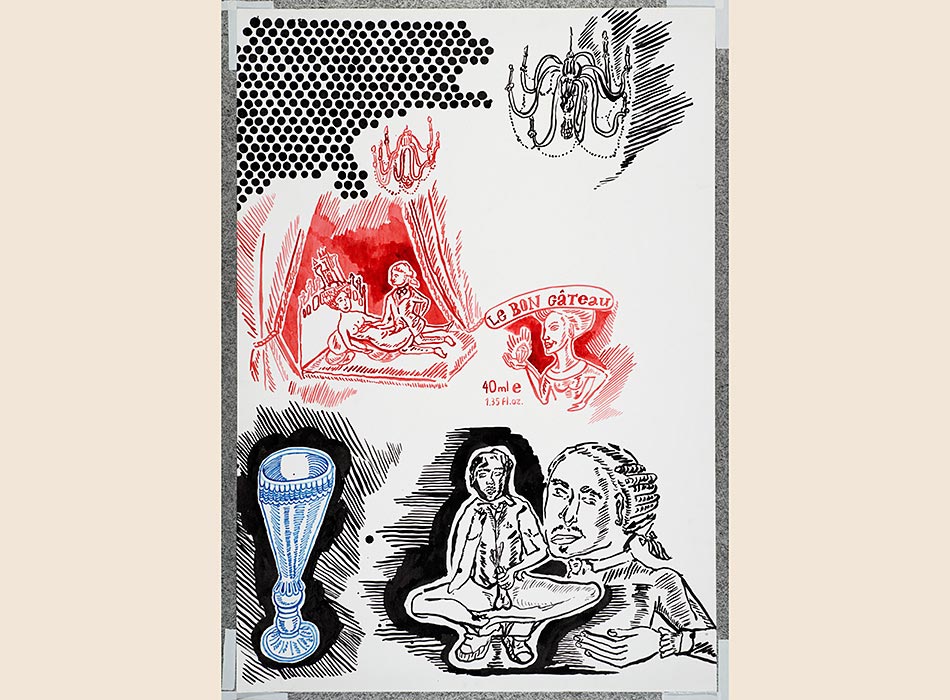

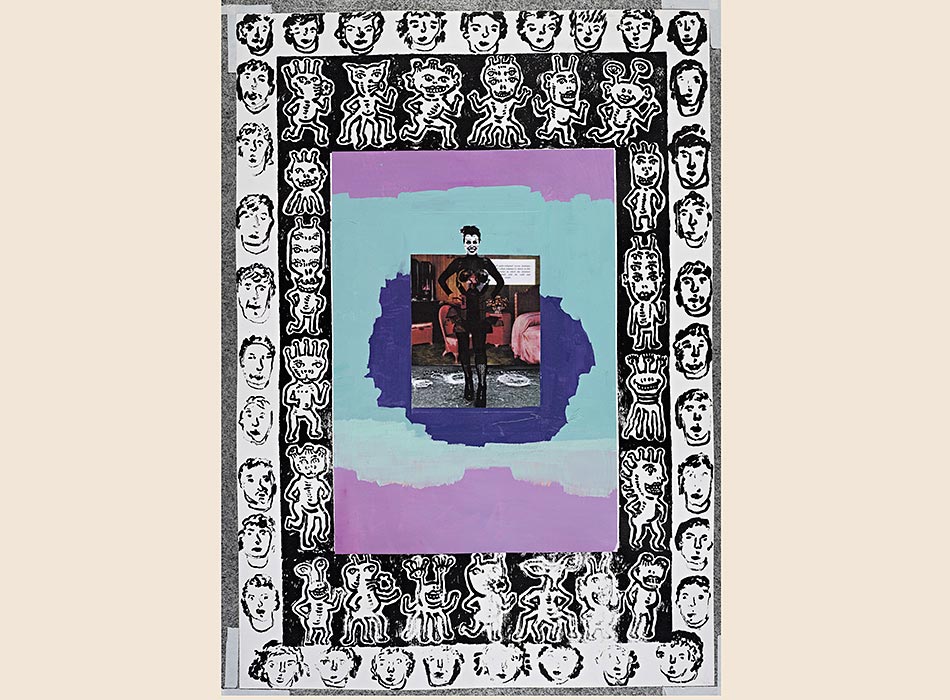

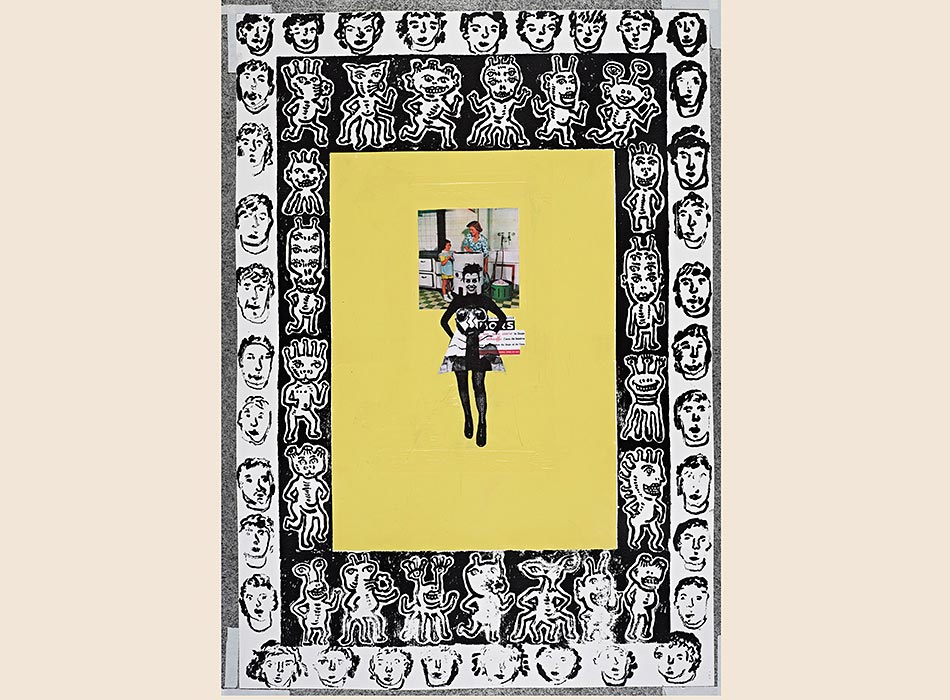

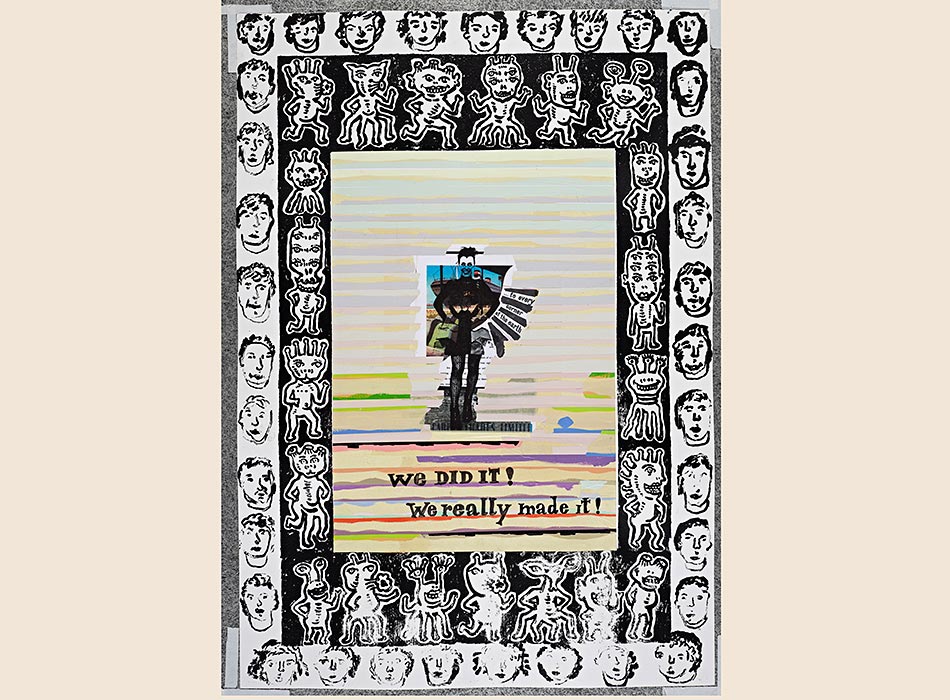

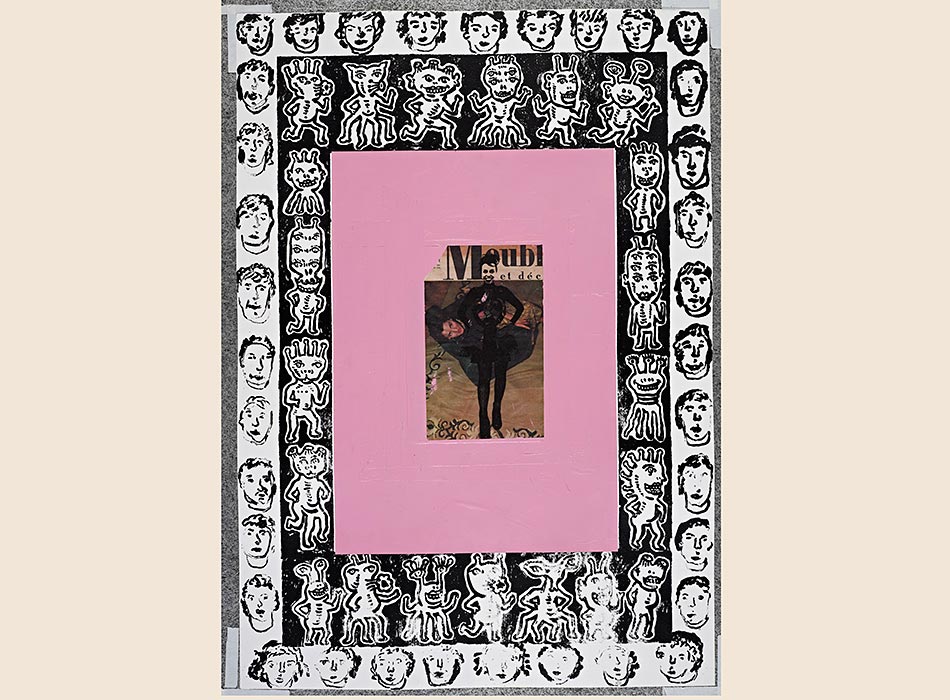

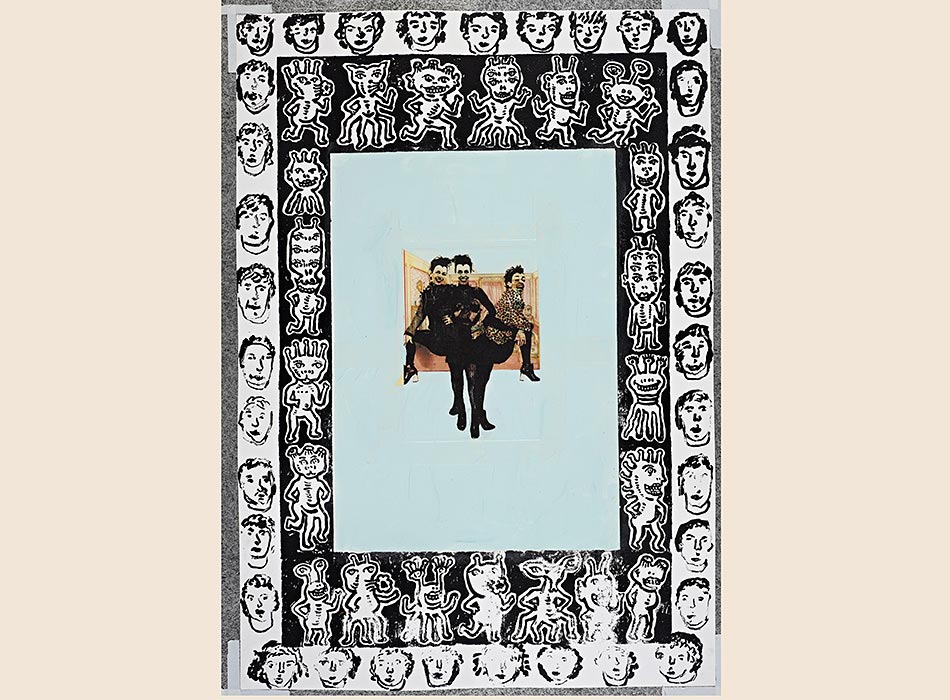

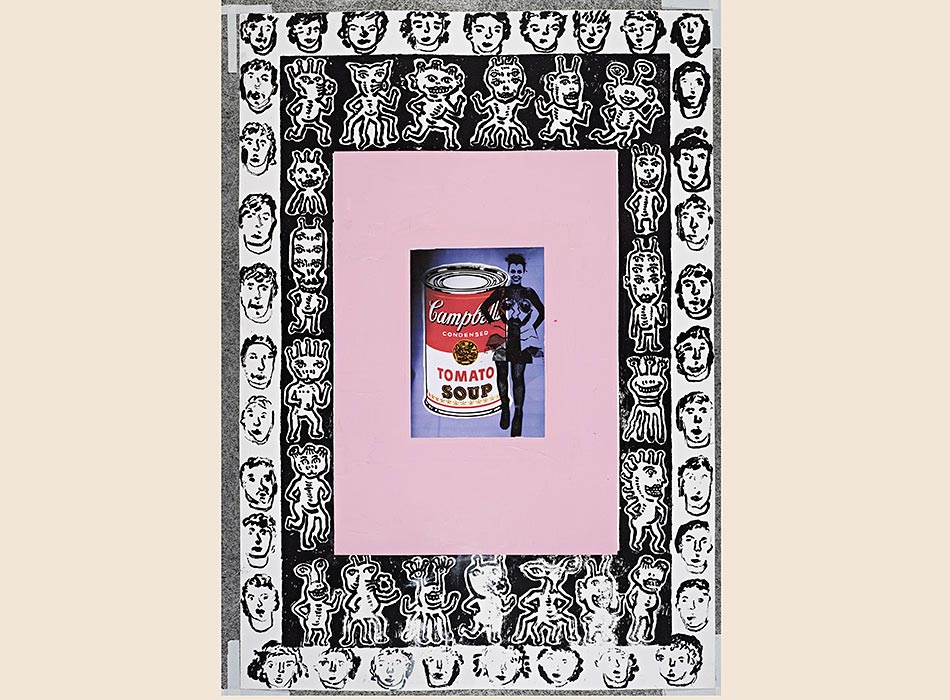

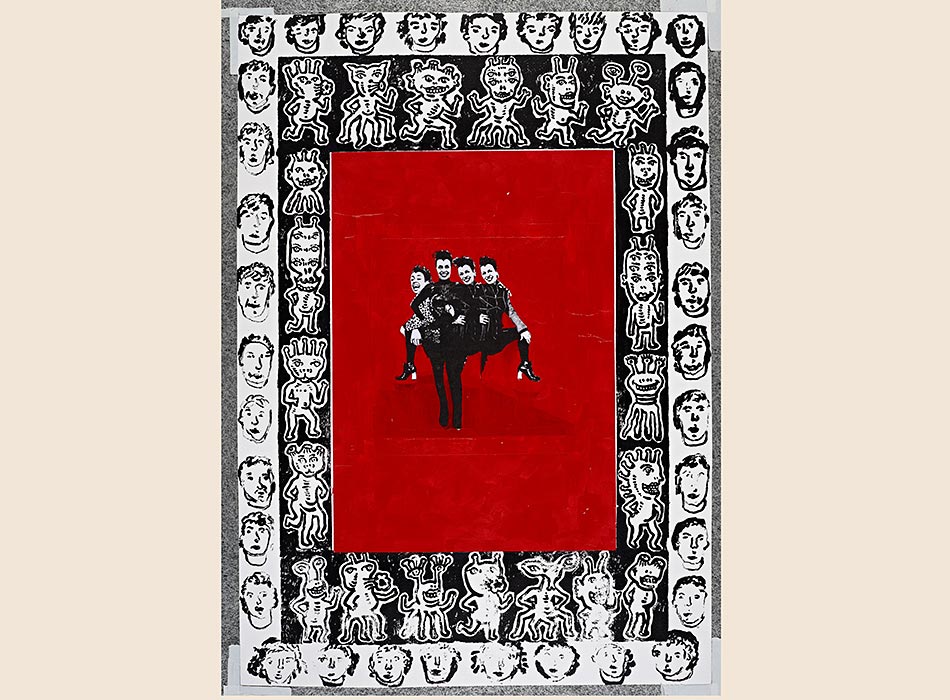

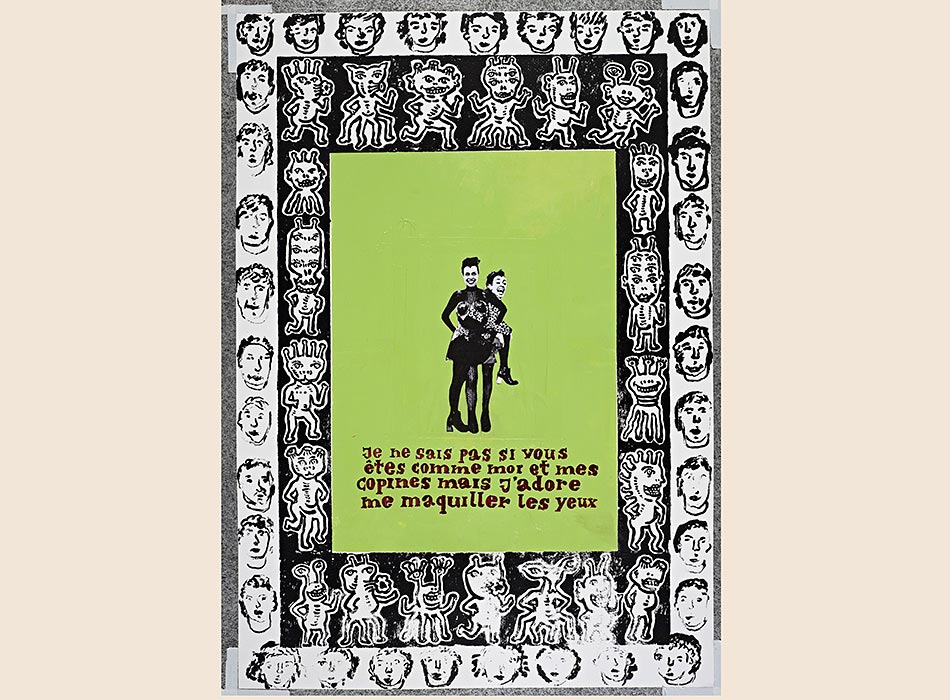

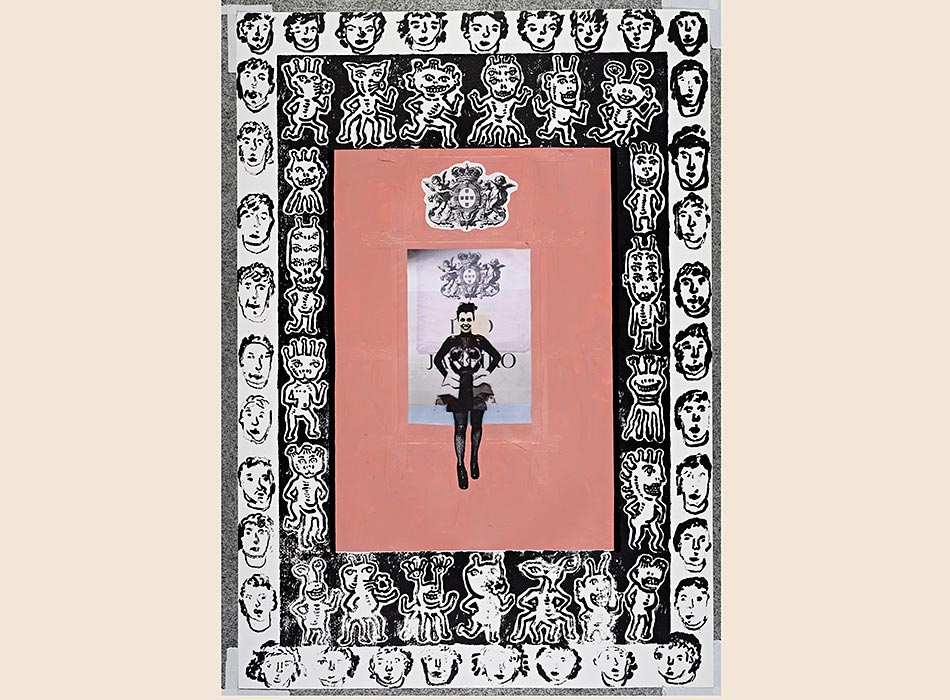

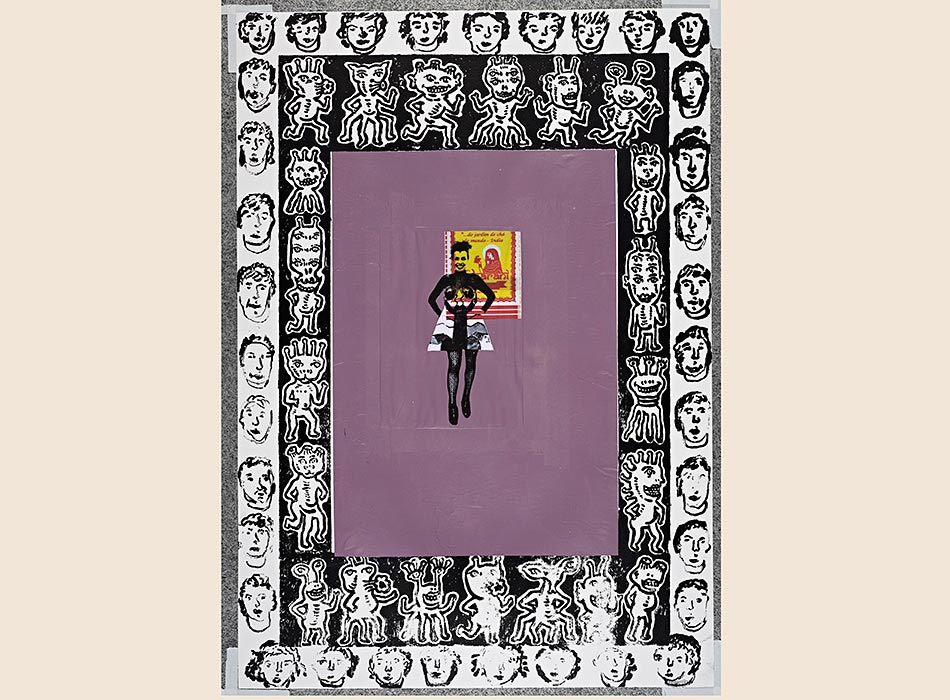

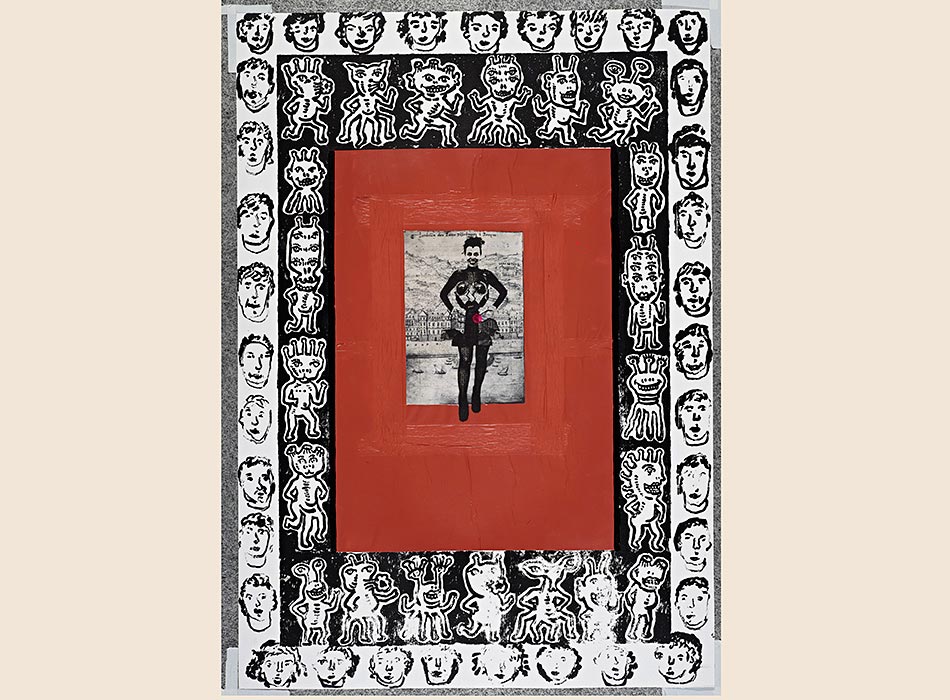

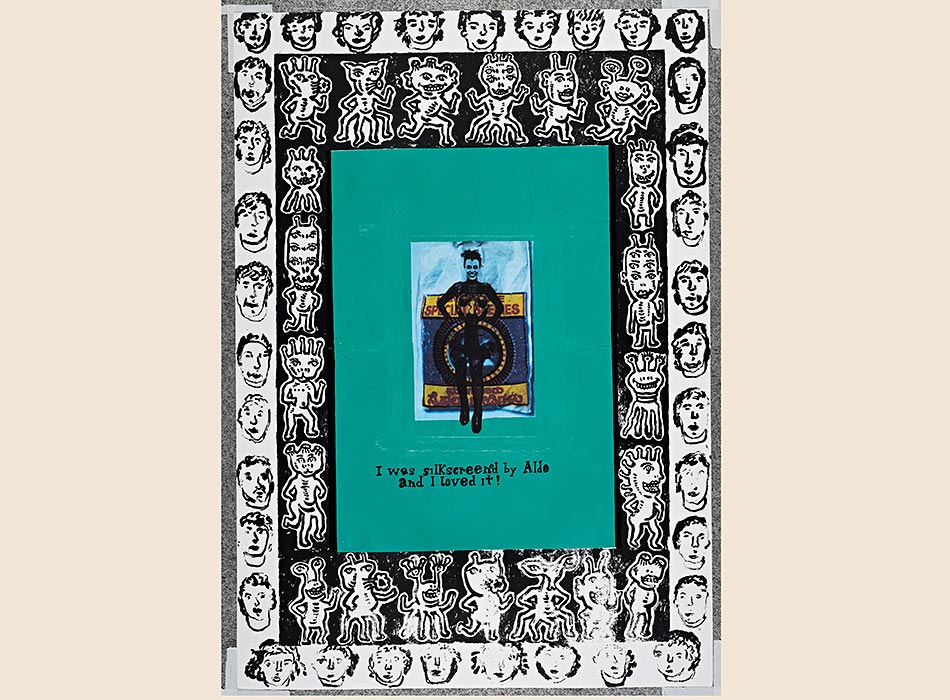

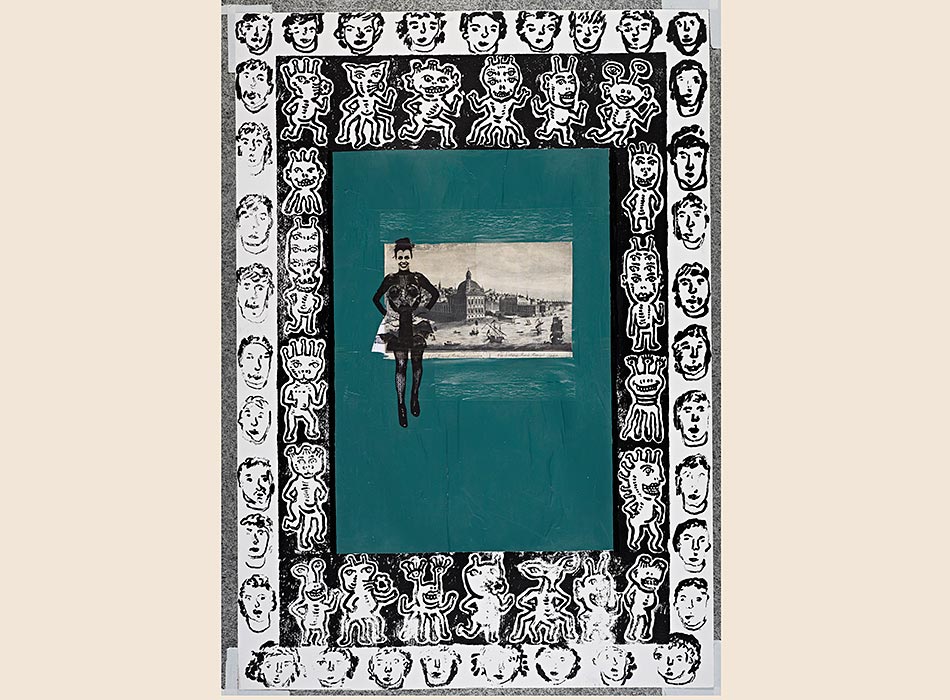

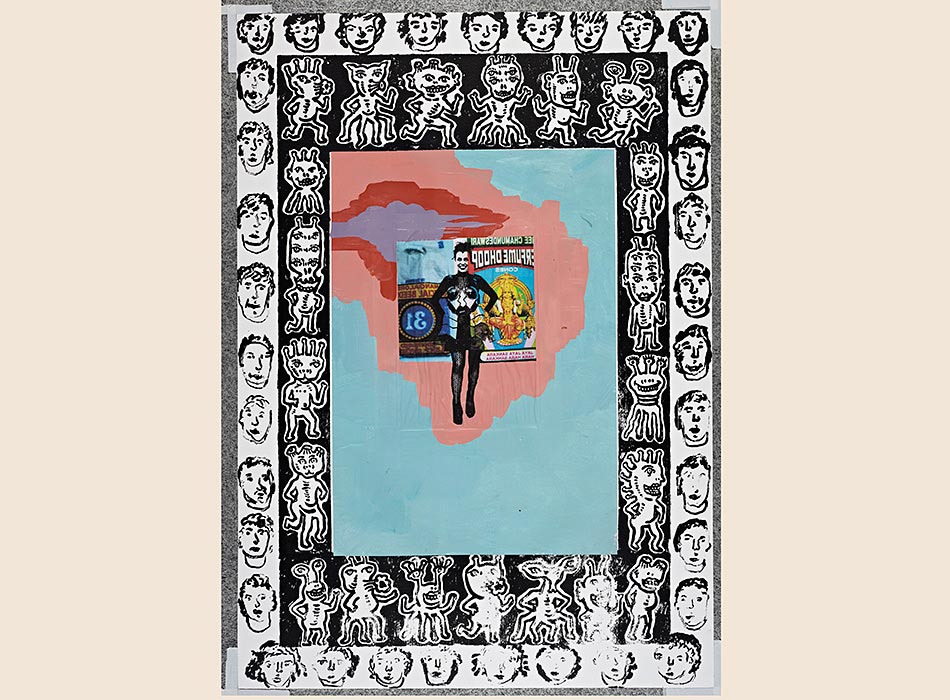

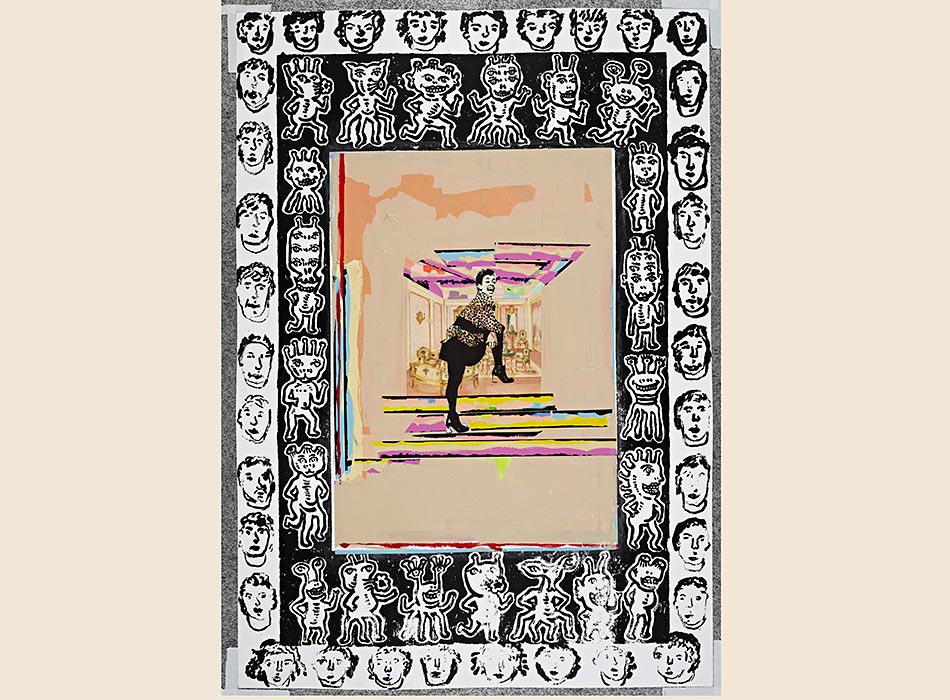

In such sense, the collages of the NYC Song Book, a sort of diary of his passage through New York, are particularly porous in relation to the very specific surroundings in which they were created. They superpose advertising images, love confessions, homo-erotic sex, noodles soup, the Beatles, all this mixed up with a graphic skill that unifies a narration that is naturally fragmentary. The collages put together several materials (photographs, comic strips, pictures from magazines, advertisements), but it is once again the drawing that makes legible and harmonizes the abrupt cuts inherent in the collage exercise, giving a sense to the visual wandering that animates such images.

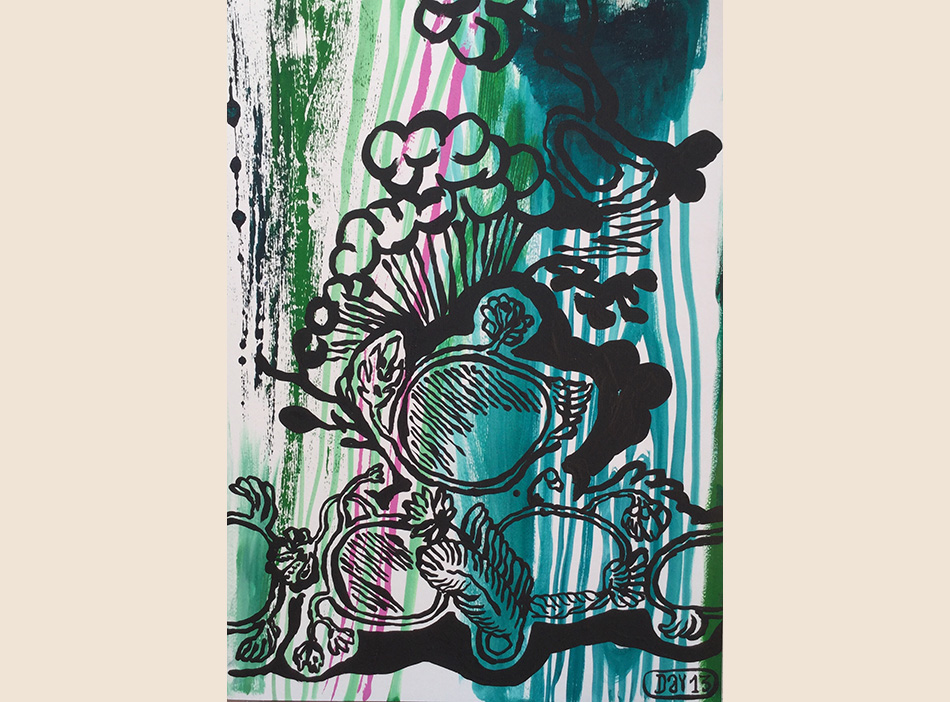

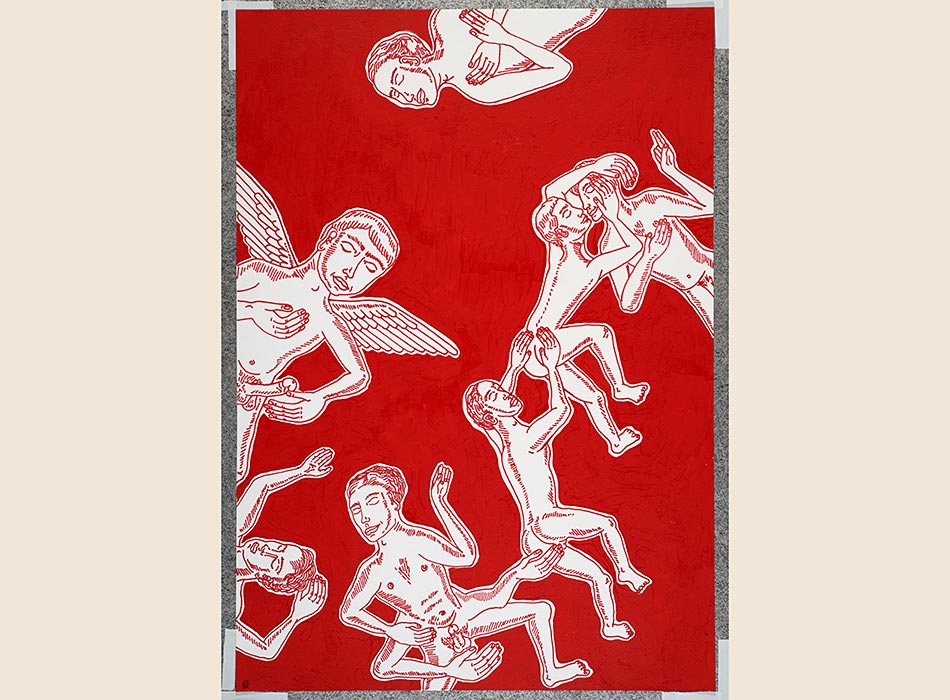

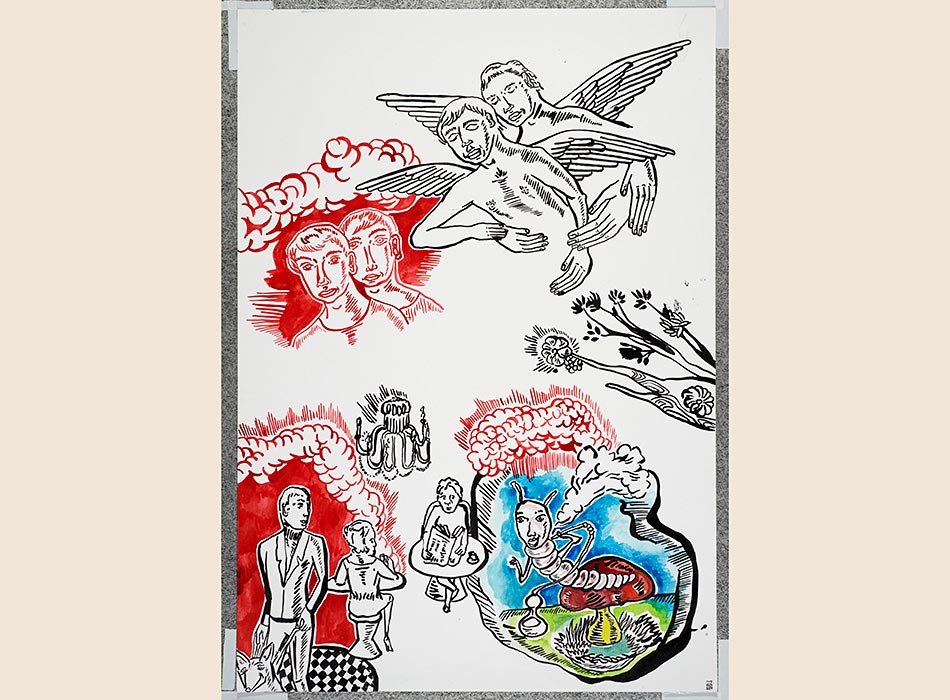

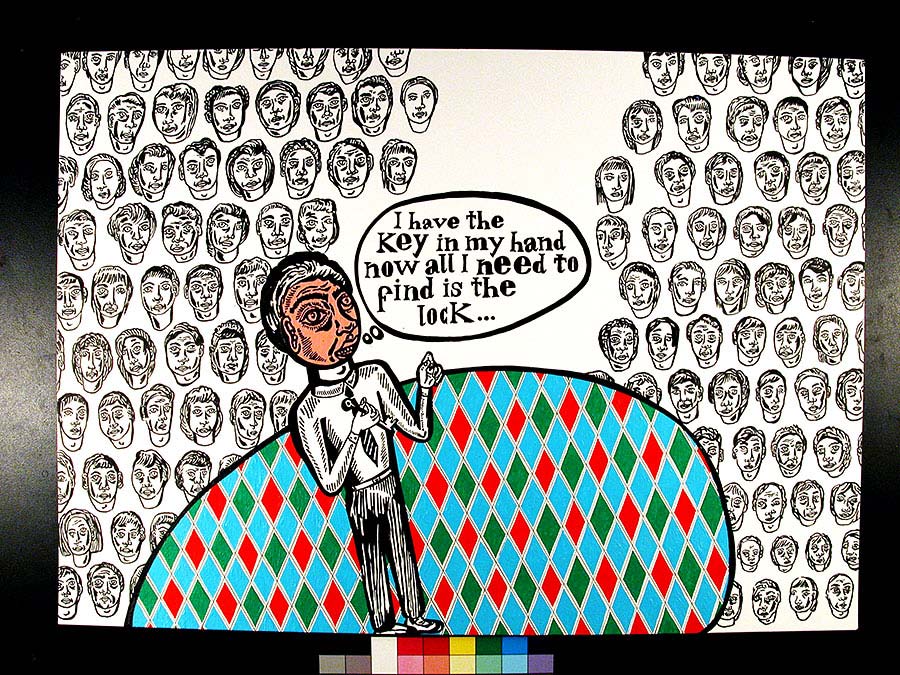

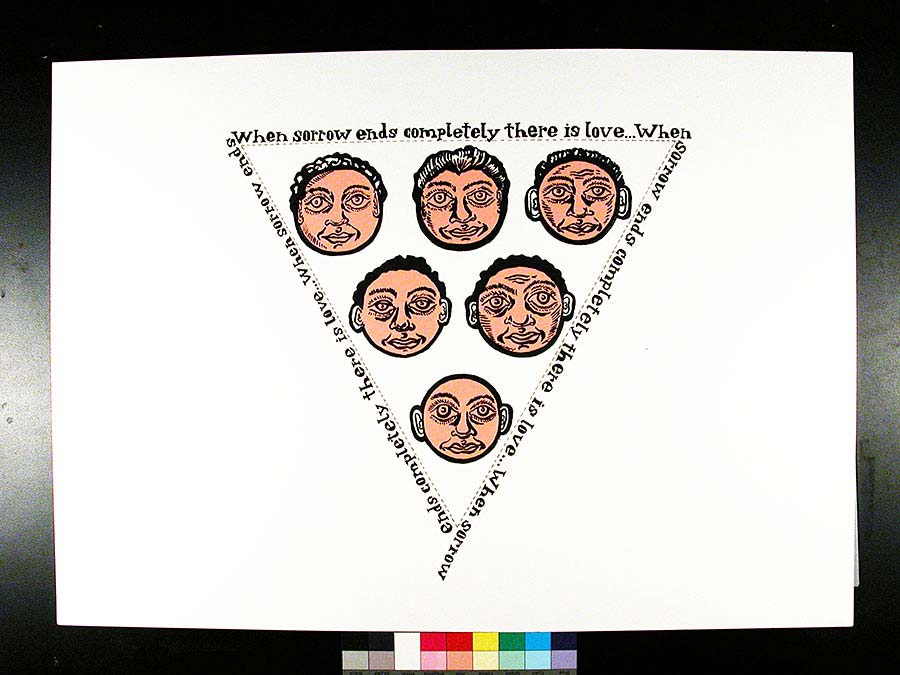

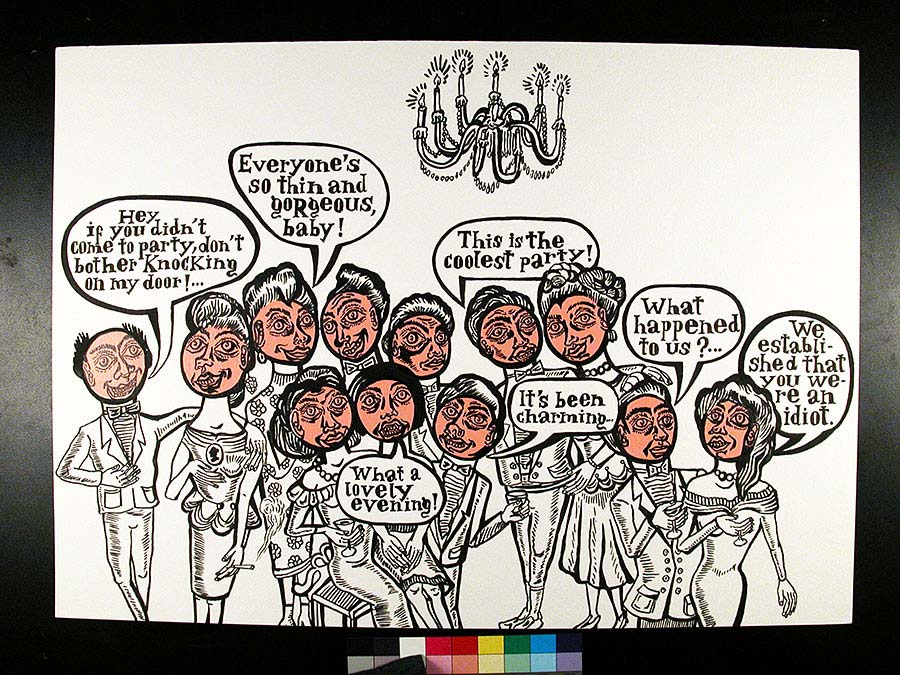

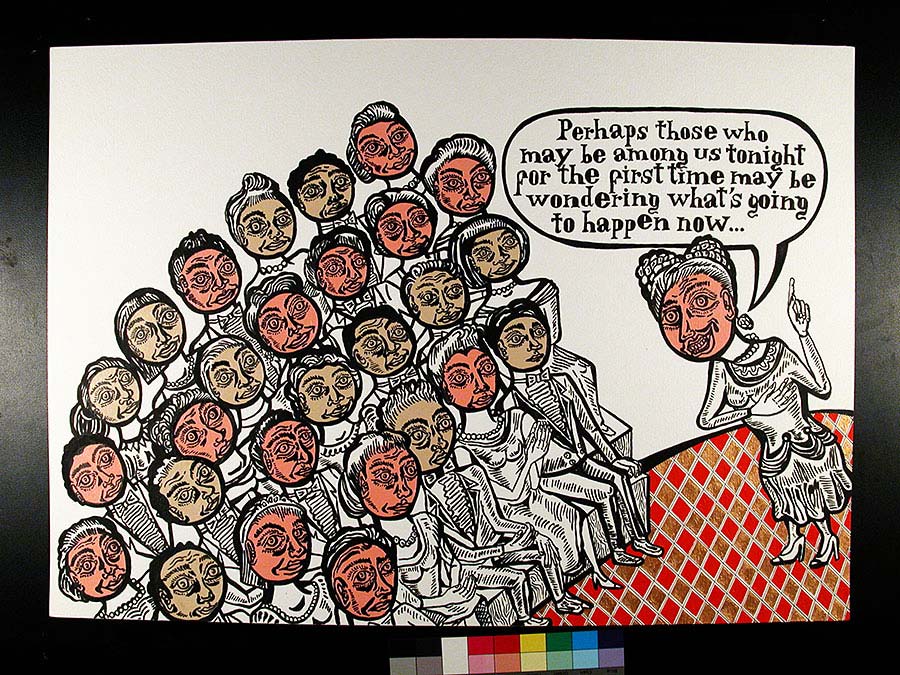

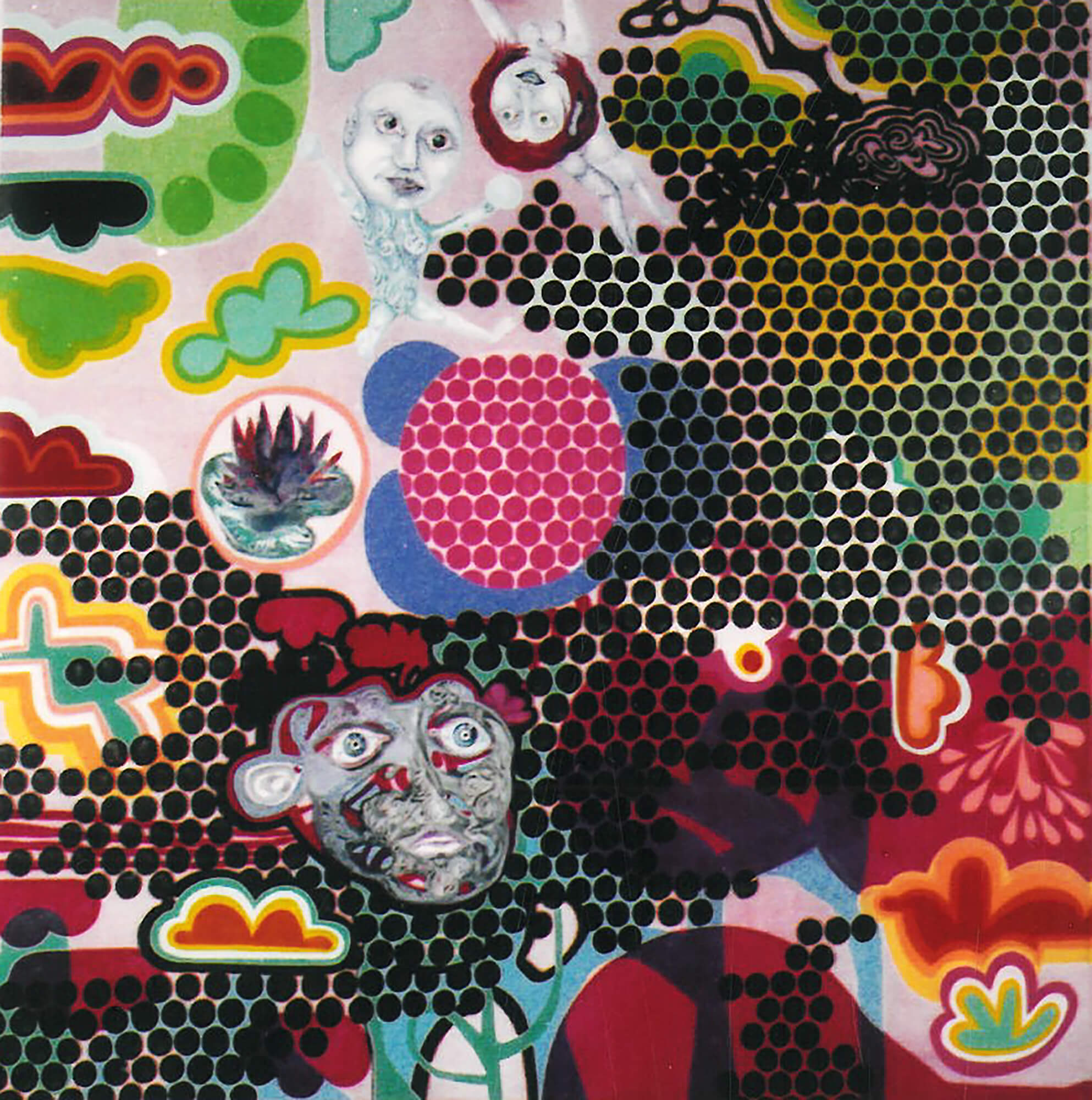

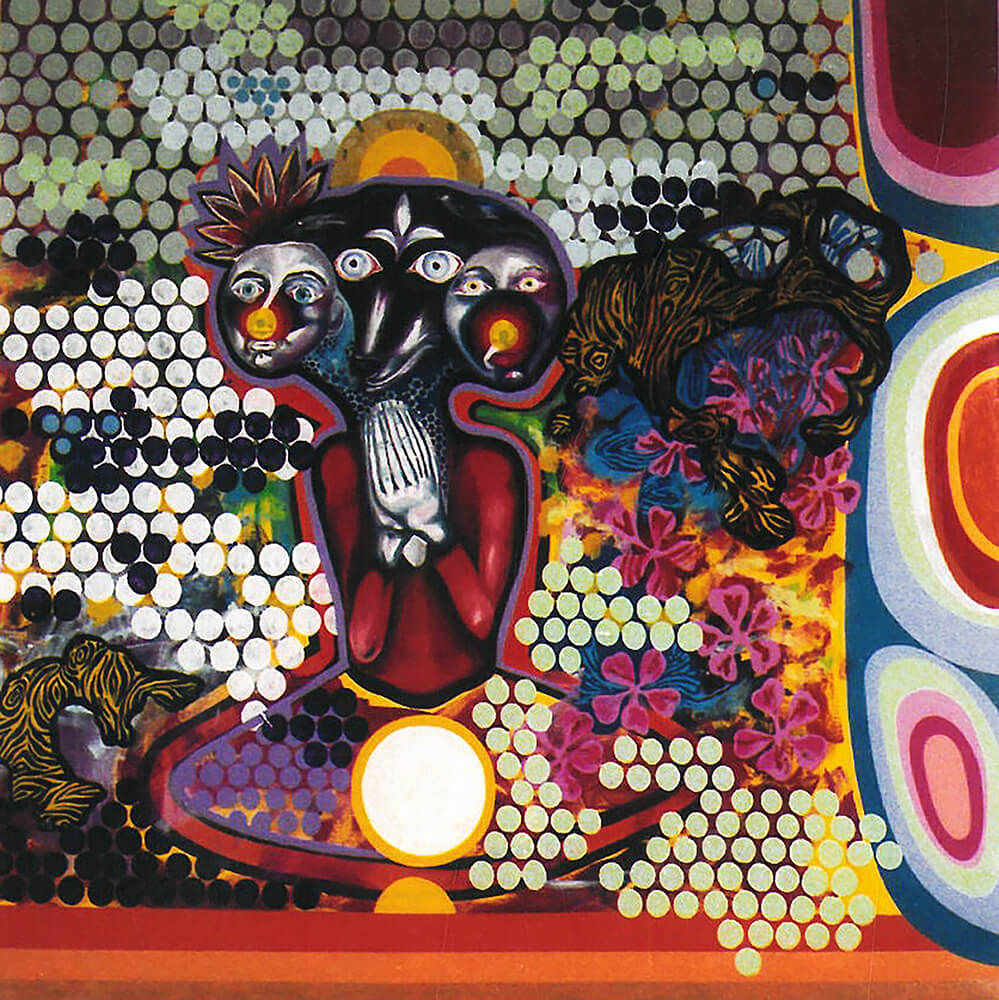

A last group of works essentially consisting of large format paintings reverts the sense of the biographical experience, of the presence of and in the world to a wider self-reference possibility. The artist represents himself in architectonic interiors with a serene or festive appearance that have a frequent emblem that lies in the archetypical image of the salon. The self-portrait breaks itself up becoming a crowd, and sometimes it is accompanied by winged angels that float over normal domestic life or participate in a dance of floating bodies. Once again it is the graphic construction, the drawing, that dynamites any possibility of realism and allows other levels of reality to come onto the surface: the scenes are shown filtered by circles that are organized as a dense filigree over the images as if they were vapours or inducers of states of mind and oniric ambiences.

Be it in the static and modular space of a salon or in the abstract transit where figures and signs mingle together, the painting of Ivo Moreira prolongs the travel since it is a travel in itself, both to memory entanglements and to the drifting territories of desire, and in such sense it is always a crossroad between times and a promise of future.

Celso Martins

Lisbon, 24 October 2009

Once upon a time in painting by Ana Roque Vaz de Barros

I’ve known Ivo’s painting for ever. More accurately for the last thirteen years years, which in terms of his painting can be said to be for ever. Therefore, I tend to say that I have the advantage of knowing him but that I don’t have the advantage of not knowing him. However, I’ve always managed to keep my distance and be objective about his work as much as about anybody else’s. So much so, that I’ve sometimes become afraid of making any comment when he asks me to, because of my inevitable candour which he knows so well. I know just how much my straightforward words can affect his pace when he is preparing an exhibition, which is why I sometimes choose to stop by his studio only once he has firmly decided upon his path. Because in the end I have to respect his choices, and I do.

I’ve seen and watched him painting. I’ve felt him painting. I know that he paints like he breathes. He needs to keep painting just as much as he needs to keep breathing to stay alive.

He paints viscerally, with an intensity that comes from the heart, his heart. And his soul. When he picks up a brush, he cannot help but depict his current emotions, his state of mind, life, to put it in a word. However, the underlying reality in his paintings stands behind what’s immediately apparent. Still, anyone who knows him truly well can many times recognize what is sometimes barely hiding behind a certain figure or group of figures, be it a pain or a laugh.

When I first met him and because of my training, he often asked me about his use of colour. I guess he didn’t realize just how well he has always instinctively mastered it in practice. In my opinion, Ivo is one of those rare painters who can get a canvas drunk on colour and still manage to have it hold it in.

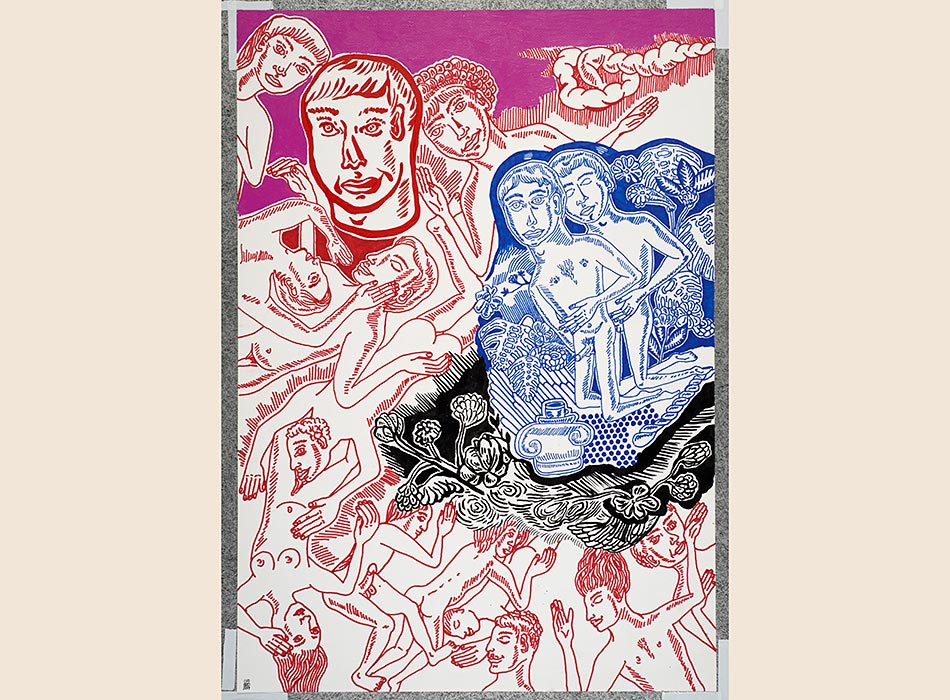

And this can been seen not only when he fills up the canvas or the paper with colour after colour, layer over layer, both inside and outside the figures, but also when he plays with the line on a coloured background. Such background can be made up of a superposition of different elements and colours or of one sole colour which is often very vibrant, particularly in the larger formats. In this latter case, such vibrancy grants the line an unquestionable primacy which on its hand makes the figures look animated, which is fairly clear in his salons recently exhibited at Sala do Veado (Gifts From Where I’ve Been, Part II, 2009). He also does this type of painting on a white or black background and it is always interesting to see the eventual similarities or differences that he manages to achieve only by changing the background’s colour and how this affects the figures he depicts. The line paintings on a white or black background also recently exhibited at Galeria Jorge Shirley (Gifts From Where I’ve Been, Part I, 2009) are a good example of this, specially when compared with the paintings exhibited at Sala do Veado since these two exhibitions occurred simultaneously.

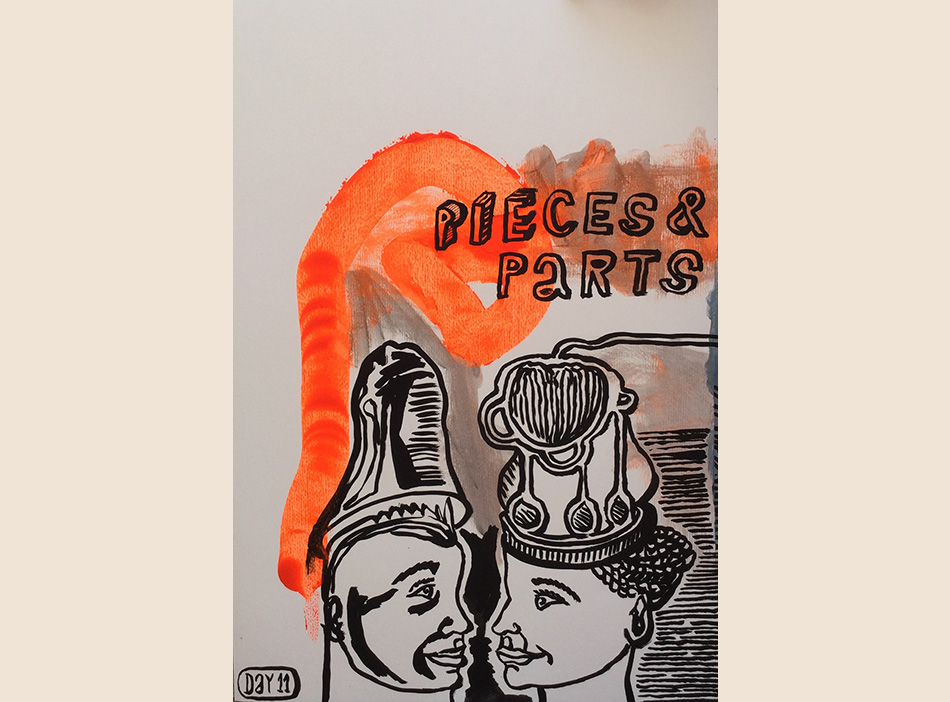

Many of his works and most of the paintings that appear in this catalogue and particularly, “The Salon” (2006), “The Banquet” (2008) and the paintings shown at his two most recent exhibitions referred to above contain a wide profusion of different elements, figures, images, spaces, eras, people, animals, people-animals, animal-people. Once again, however, and just like it happens with colour, they all seem to be perfectly at ease and to belong where they are, and there is no apparent resulting anachronism or misplacement. This seems to show that there is hope that peaceful coexistence is possible in more ways than one.

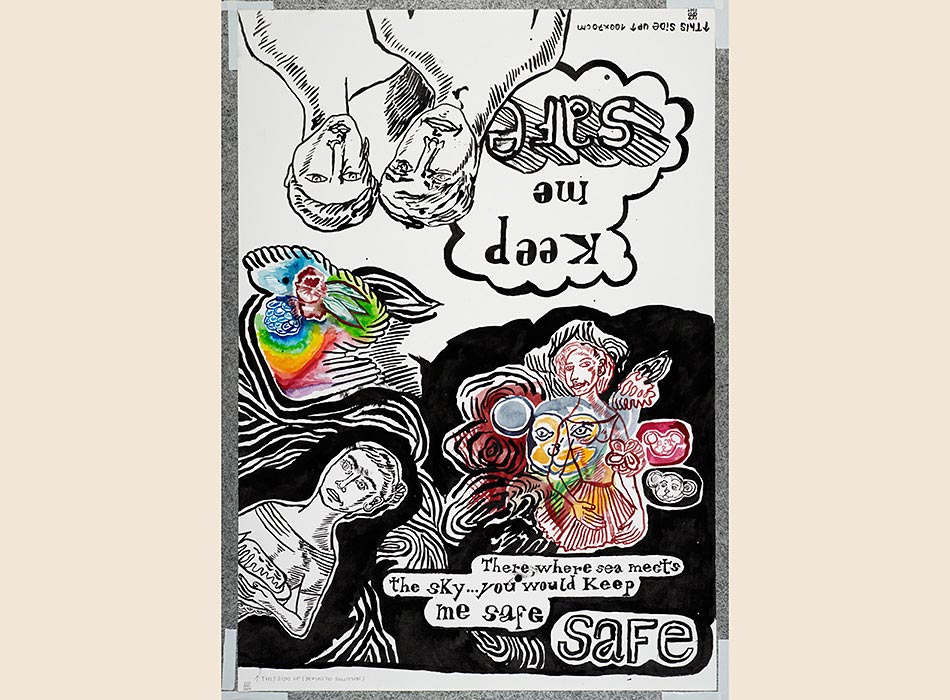

In other paintings, sometimes an intriguing entropy slowly becomes a strange and enticing harmony, even though the achieved balance may seem to be about to explode and hit you right in the face, at any moment. I know this may sound like a paradox but it isn’t. Randomness and chaos are present in some of his paintings just like in life itself, but somehow so is homeostasis. The thrusting entropy in such paintings does not hug you at first, rather sucking you into an endless whirlpool in just one gulp. Nevertheless, you feel you have to stay there and let yourself be pulled into it by an almost hypnotizing force. That is why you can see people frowning awkwardly when they first come across one of such paintings, and later on falling into a state of unexpected bliss (first you find it strange, then it becomes a part of you).

The dynamic in his paintings can sometimes be disturbing. The thriving dynamic between the pictorial elements and the colours can make you believe that the work is always in progress, and that the characters are always in constant mutation or about to move into another place within or outside the painting, a true journey inside a journey, where the unreal can turn into real within the time-space of the canvas. This leads to feeling that the figures may come alive and jump right out of the painting and either caress you or harm you. His characters may seem to be as much of this world as of an oniric or fantasy world, or of our subconscious world, or even of an unknown world still to come. You may be watching a figure’s eyes (sometimes several pairs of eyes) in a painting and end up feeling like you are being watched yourself. And we all know this is not always pleasant.

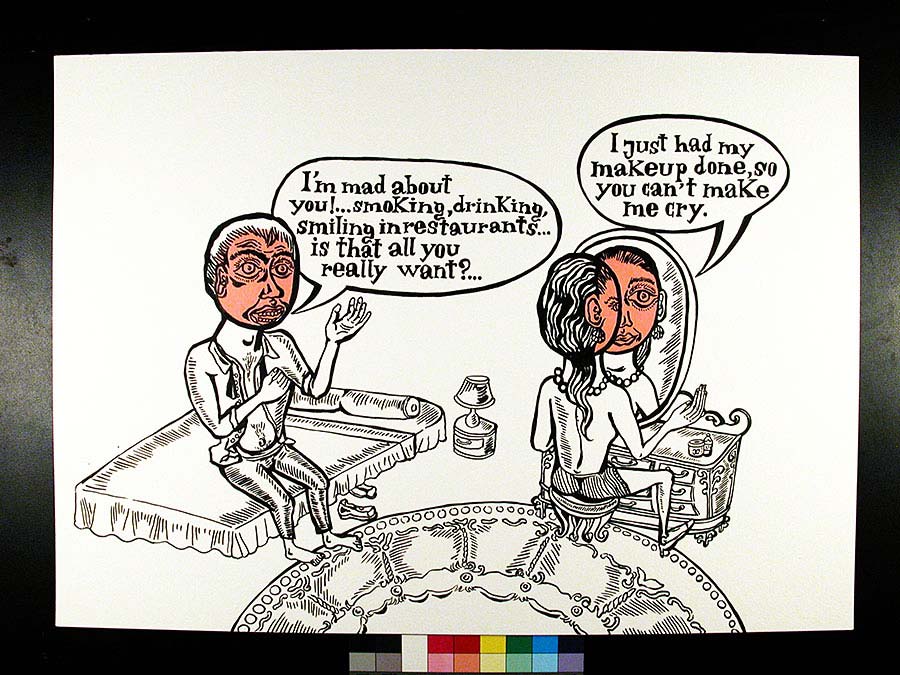

Nevertheless, I’ve seen many people feeling uncomfortable looking at one of his paintings, and then smiling or even laughing in just a matter of seconds, when they look at the next one. This ability to jump from fright to humour, and even more so to make them coexist in one very same painting, although people do not always realize it, is a very characteristic trait of Ivo’s work.

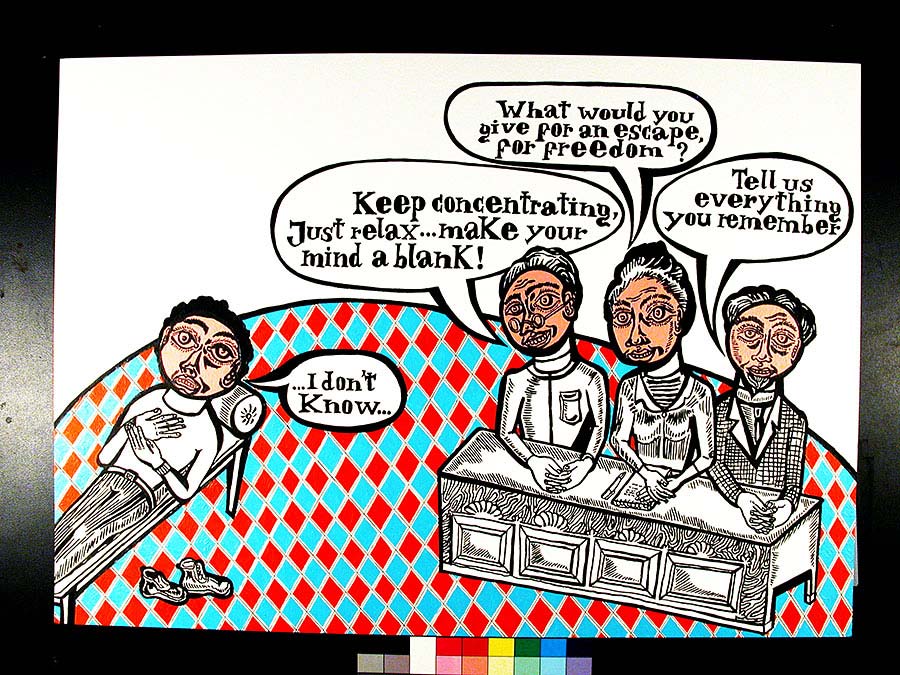

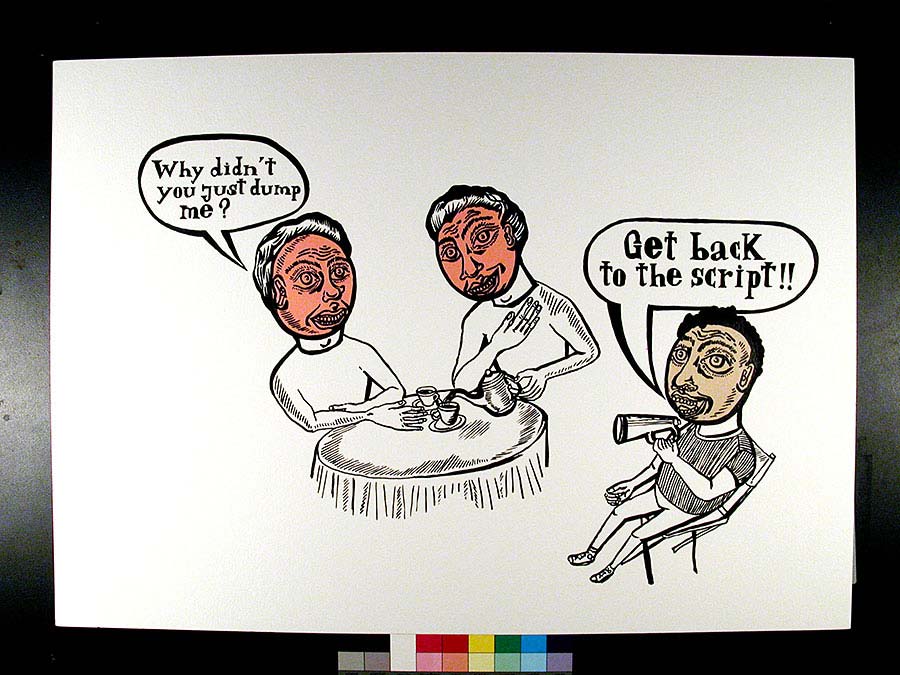

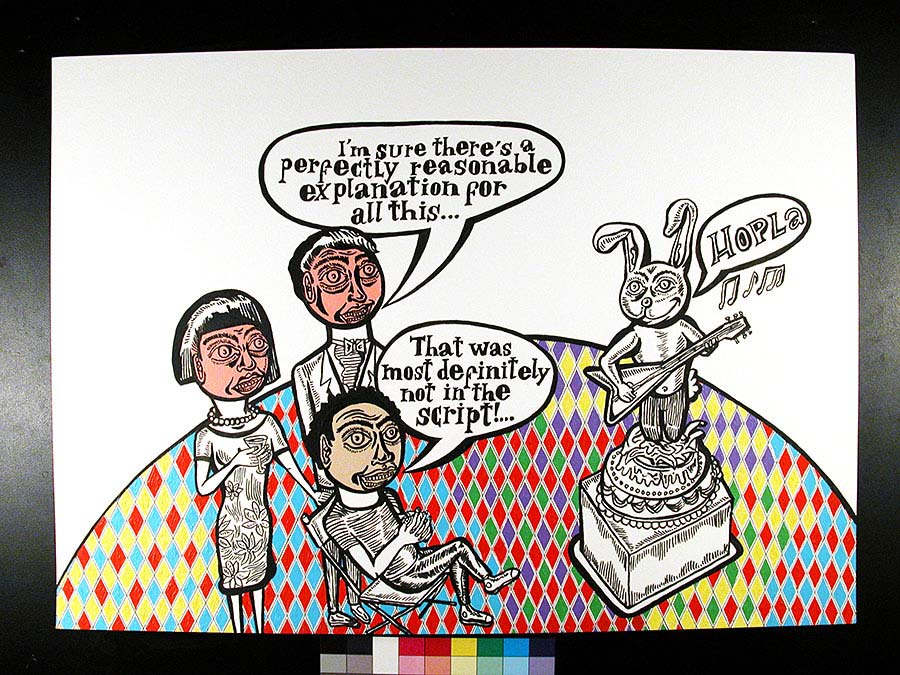

In one same painting he can appear naïve, almost childish, and at the same time be satirical to the point of utter insightfulness. This frequently occurs in his paintings in which he depicts scenes from art openings, social events, parties, banquets and everyday life. People often manage to see themselves portrayed whether they are his friends or mere observers. In his Graphic Diaries and Artist Books, these characteristics become easier to apprehend because such intensity is confined to the very boundaries of every sheet of paper on the one hand, but also repeated over the several sheets of paper on the other. And this is often frosted with a bitter-sweet layer of collages and humorous text that truly puts the icing on the cake.

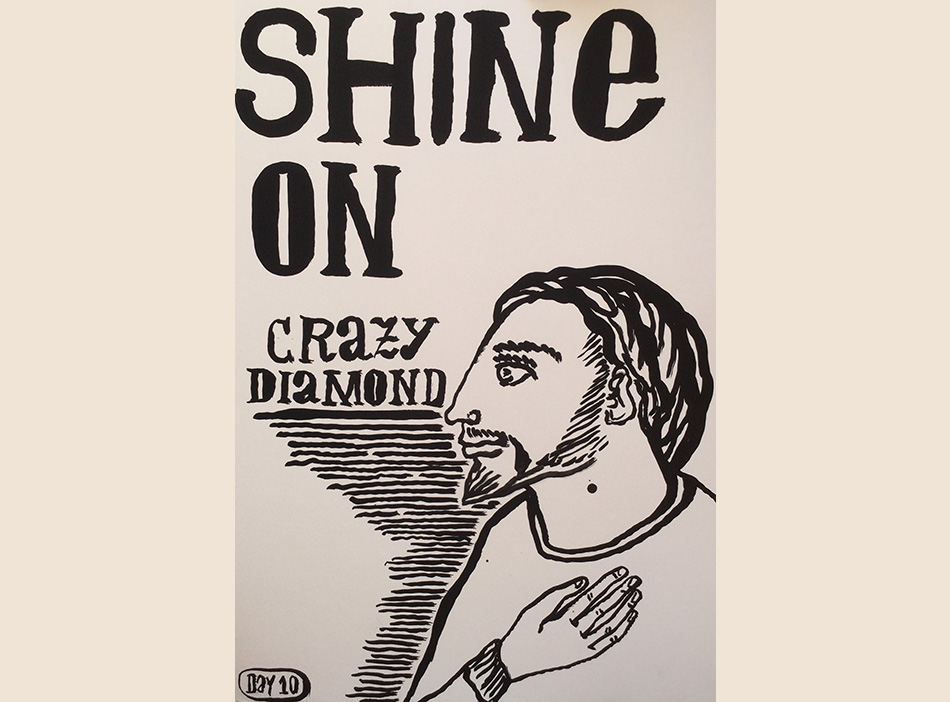

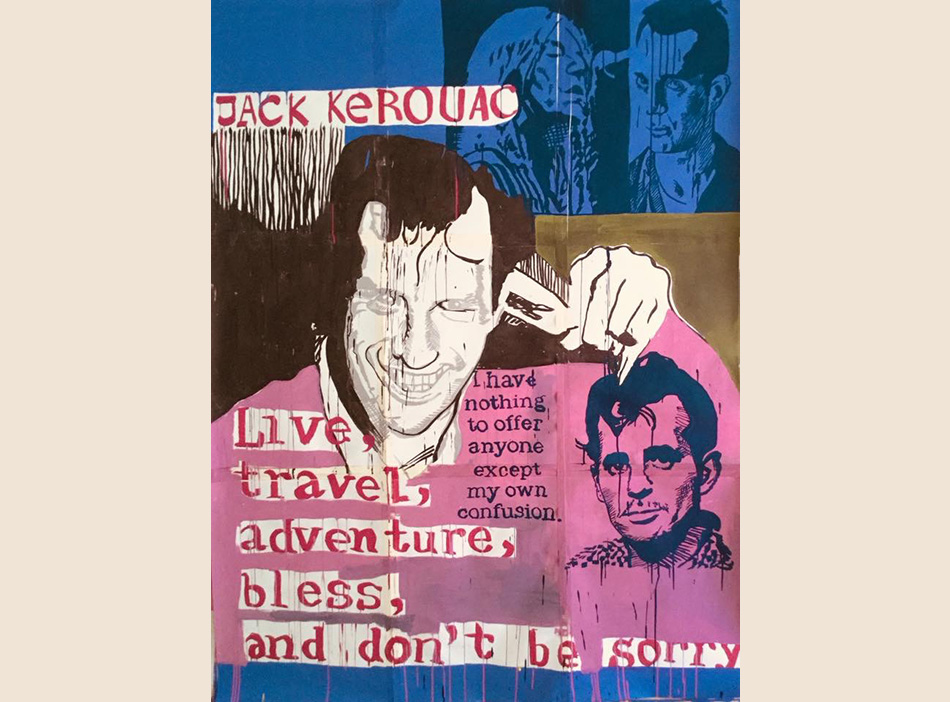

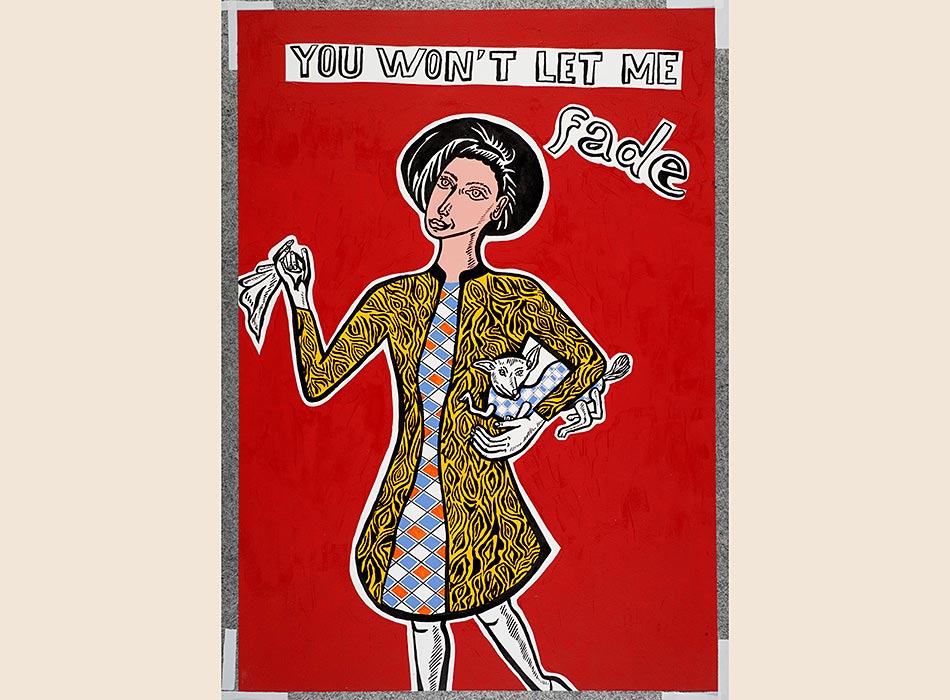

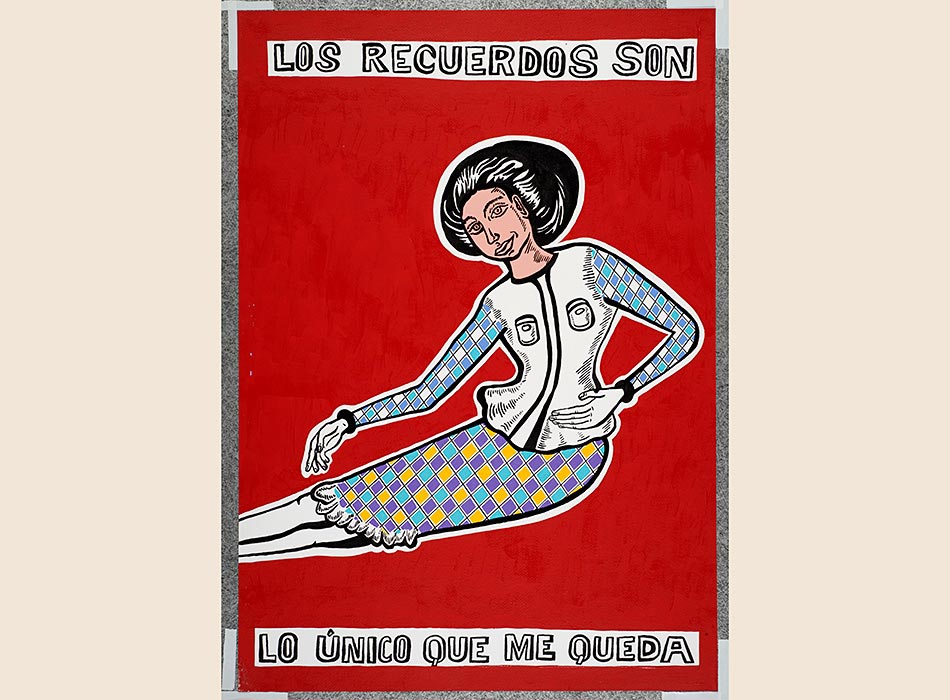

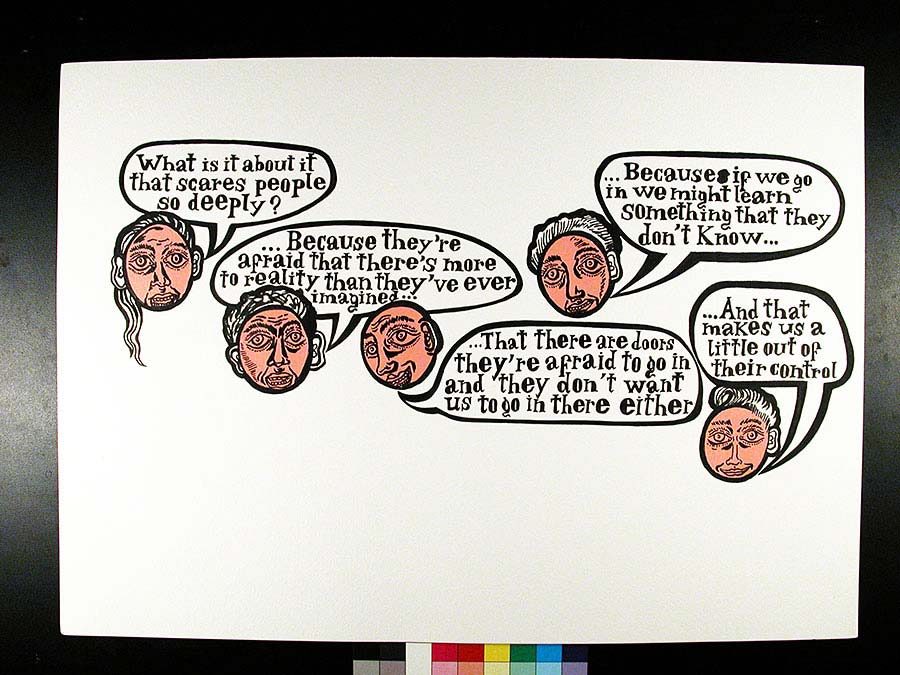

He also uses text in some of his paintings but not necessarily as a humorous element. Sometimes such text serves as a means to achieve the purpose he is ultimately aiming at. Some other times, the words operate as a subtext or a musical background (both metaphorically and literally) since he does not only use his own words, but he also quotes some poet/singers that particularly touch him and which he listens to while he is painting. Thus, this is not a mere appropriation but rather a tribute to the respective authors for the empathy they make him feel with them.

Like so many other painters, he has made several self-portraits throughout the years. However, his self-portraits are neither a narcissistic exercise nor a mere means to register the passing of time. There are basically two different sides that can be read in his self-portraits. On the one hand, he paints them when he does not know “who or where he is” in his relations with the world and with others. These are moments of doubt when he needs to make some soul-searching and self-analysis, through which he plays a sort of ritual that enables him to reach personal metamorphosis. On the other hand, he also paints them when he knows exactly “who and where he is” and feels happy about it. And these are moments of harmony that he wishes that could remain unchanged for ever and which feels deserve to be celebrated.

At a certain phase of his painting, his characters had more than five fingers each, sometimes ten, maybe twelve. This seems to express a sense of people’s inability to fully hold onto what is really important, metaphorically telling us that somehow our hands alone never seem to be enough to fully reach out onto the world, our friends, life, love. This shows that Ivo is not afraid of displaying and sharing his personal emotions, which does not frequently and overtly happen in contemporary art, but at the same time this reflects particular moments of sadness or happiness which we can all relate to because they are universal. Not only does this have to do with the individual’s eventual inability to act but also with the constant feeling of lack of time in our day and age, which are both universal.

Another very important trait that is linked to Ivo’s work is that he is an innate traveller. This has been the case of numerous artists throughout the times not only in visual arts but in art in general. For some artists, however, the outcome they get from reading about other artist’s travels or seeing other artists’ works is sufficiently inspirational. This is not the case of Ivo. For him, travelling has to be real, he has to breathe the local air. There are times when he begins to feel void of a reason to paint where he absolutely has to leave and go somewhere. Most of such times and for some ineffable reason, he knows exactly where he needs to go. This happened in 2000 when he decided to once again travel to Brazil (Salvador da Bahia), but it is specially the case of India where he went in 2003 and ended up staying for one year, and where he intends to return very soon. What he brings back from travelling, be it corporeal or incorporeal, always reflects itself in his work. He registers his travels in graphic diaries in which he draws, paints, makes collages using local everyday materials (such as packages, labels), and where he inevitably writes about the cultural specificities of each place, but also about the smells, the sounds, the colours, the light, the music, the interaction between people, his sensations and his thoughts. He always comes back from his travels with a kind of almost touchable brightness that can actually be felt in his mood and in his words. That is why his travels inevitably lead to talking about his mysticism.

His mysticism has always been a part of him, although he has probably become more aware of it when he began travelling more frequently. And this increasing awareness of spirituality as a corner-stone of his life has made him feel the need to convey it onto his work, which is why we began seeing the iconography of the sacred incorporated into his painting. You can see several gods and meditation or praying scenes depicted. On the other hand, many of his characters even some of those that may appear to be utterly secular have gained wings. This has to do not only directly with the sacred, that is, they are not necessarily true angels, but also with the belief that everybody should be able to fly wherever and as far as they want to, as long as they acknowledge the inherent role of spirituality. And it cannot but be curious to notice that when the wings began to appear in his work the hands went back to having five fingers.

Although underlying links between his work and the work of several artists can be recognized (Keith Haring, Francis Bacon, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Frida Kahlo, Damien Hirst, Francesco Clemente, just to mention a few, and with no concern for any particular order), and the same goes to say about the art movements associated with , what he has retained from their work is not mimicked, it has been digested and transformed into his very own pictorial language. His work is a true fusion of art and life and although he is not the first one to do this and he will certainly not be the last, he does it following his very own path.

In reality it is clear to see that Ivo is not concerned about fitting into any mould. His main thriving motivation is to keep on painting to keep on living, always. And it is a well-known fact that the excessive need, sometimes almost the obsession, for artists to want to belong, or for others to want to place artists, or people for that matter, within certain rigid frameworks, currents, categories or “files”, may well operate as a discouraging rather than a catalyst element for new quests and discoveries. The concept of being an artist is closely linked to the concept of independence in the widest sense of the word, and this has been a struggle fiercely fought over the centuries. Nowadays, in the 21st century the freedom of the spirit of art has to be an undoubtedly earned right. And the truth is that the fear of being different never led anyone anywhere.

Ivo goes beyond what is known as reality to share his life with us, we may as well accept this gift from him.

Ana Roque Vaz de Barros

26/10/2009